Woody Allen’s Crimes and Misdemeanors Guilt Complex

Written by: Wade Sheeler, Special to CC2K

The Black Maria’s Wade Sheeler reviews Woody Allen’s Crimes and Misdemeanors, recently released on blu-ray from the boutique label Twilight Time.

Watching any Woody Allen film today brings a whole load of baggage along with it. Deeper meaning, revelatory dialogue, scenes, jokes, plots – everything is up for reinterpretation and dissection. However you feel about the disturbing accusations, currently you can’t shake the stigma. Thus it was with this newly inherited “baggage” that I re-watched the recent Twilight Time Blu-ray release of his 1989 film, Crimes and Misdemeanors.

As much as Allen denies it, much of what happens in his life finds its way into his creative work. And, whether or not you wish to prescribe to this type of reductive analysis, you can’t argue that by the late ’80s and early ’90s, Allen’s films took on a decidedly darker tone, as he was most probably working out some issues of guilt, fate, spirituality and culpability. Three years later, he would separate from his longtime companion Mia Farrow, upon her discovery of his affair with her daughter, Soon-Yi (now Allen’s wife for over 15 years).

Crimes and Misdemeanors follows two stories: one of a successfully married ophthalmologist who has been having an affair with a flight attendant and the other, a documentary filmmaker on the downslope of a failing marriage who has the opportunity to direct a filmed portrait of his brother-in-law, a successful TV producer who he can’t stand. The ophthalmologist, Judah Rosenthal (Martin Landau) is being hounded by his mistress who threatens to reveal everything if he doesn’t divorce his wife and run away with her. He is pushed to distraction and calls in his brother, Jack (Jerry Orbach), a fixer of sorts, who arranges and engineers her death. The result of which cause Judah such guilt, that the self-described atheist begins to cling to his Orthodox Jewish upbringing and grapple with the meaning of life and the spiritual implications behind murder.

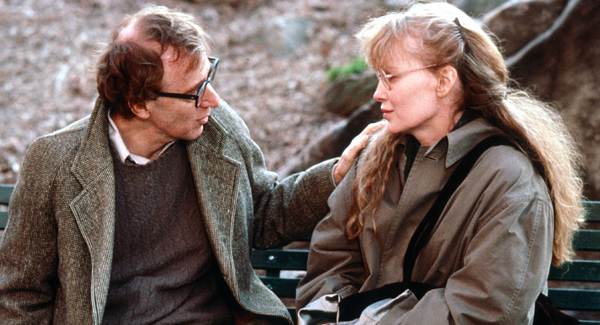

Meanwhile, the filmmaker (Allen) takes on the assignment of directing TV egomaniac (Alan Alda) Lester’s documentary because he needs the money. But along the way, he falls in love with an Associate Producer, Halley (Mia Farrow) who Lester also has designs on. Allen’s Cliff doesn’t suffer from guilt as much as depression over the situation, and severe loneliness.

Allen brings in all manner of voices and opinions on faith and sin; using his favorite inspiration of course; namely, classic film clips where the scenes mirror what his characters are going through. The conceit is that the scenes are from movies he takes his niece to see at a revival movie house. From a quarreling couple from Hitchcock’s Mr. & Mrs. Smith, to a mobster planning out the murder of a blackmailer from This Gun For Hire, these clips offer a great counterbalance to the intellectual and theoretical arguments brought about by rabbis and philosophers, parents and siblings, also quoted and characterized throughout.

But like the classic Dostoyevsky novel that the film’s title is based on, the protagonists constantly weigh their “sins” to determine if they will be caught–or should be caught. While Crime & Punishment’s protagonist, Raskolnikov, murders as an exercise and self-analyzes his own guilt, Judah, too, questions his place in society; why should he live and another die, just so he can “sleep at night?” But like all of us who want a bad thing to just “go away,” he pivots from self-loathing to self-gratification.

And while Allen is not one for heavy symbolism, there is great meaning behind Rabbi Ben, played by Sam Waterston, who is the link between the two stories. Judah asks him advice while doing his eye exam, and even “imagines” the rabbi there when he is seriously considering murder. And just as Justice is blind, Waterston is literally going blind, so by the end, this kind soul, who is the most spiritual of all the characters, suffers more than anyone. As well, the highly respected Professor Levy that Cliff is painstakingly making a documentary about on his own dime and time, whose sound bites about spirituality and affirmations of life play like a haunting melody throughout the film, commits suicide. There’s no debating the themes at play; Allen at this point is a cynic of the first order.

Allen would continue going darker still, with Husbands and Wives (1992) and Deconstructing Harry (1997) still to come. And even though the former was made as he and companion Farrow were falling apart, there are clues, even in Crimes and Misdemeanors, that Allen’s predilections would get the best of him; not the least of which is his affinity for his 13 year old niece in the film, nor any of the young girls his characters have had infatuations with in his previous works.

But none of this takes away from the excellence of Crimes and Misdemeanors. Less about star power as some of his casting choices have been, here he uses the right people for the roles. As Landau does his arguably best work as a man eating himself alive, so does Alan Alda as the hysterically superficial and pretentious TV producer, and Joanna Gleason as Allen’s wife– you can literally feel her skin crawl every time she’s in his periphery.

Both stories would be a little too lean if they stood on their own, but together they make good companions. Allen’s tale offers up humor with some of his best lines in recent years: “I wish I had met him before my marriage, It would’ve saved me a gall bladder,” and “Where I grew up in Brooklyn, nobody committed suicides. Everyone was too unhappy.” And a scene from his documentary on Alda is truly sidesplitting. But the severity of Landau’s story and the loneliness that Cliff endures makes this a drama first and foremost, with some comedic moments.

While Annie Hall was considered a turning point in Allen’s filmography back in 1978, we’ve since seen the many curves his road has taken since. But Crimes and Misdemeanors, which arrived on the tail of two of his more morose “serious” films, September and Another Woman, was not just a harbinger of themes to come, but his return to deftly combining comedy and tragedy. It’s an important film not just in the Allen canon, but in any film history overview.