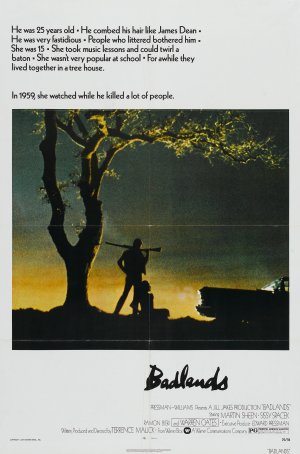

The Early Films of Terrence Malick: Badlands

Written by: Pat King, Special to CC2K

In the first of a two-part series, film guru Pat King takes on an all-timer – Terrence Malick’s Badlands.

You’re right. It is insane to try to discuss Terrence Malick’s two early feature films in the space of just two short articles. But I’m going to try, starting with his first movie, Badlands. I want to do this because Malick’s new movie, Tree of Life, is coming out in May and I want to start talking about the man’s work right now. I don’t know if I can convince anyone to see the movie, but I want to make my best effort. I’m an atheist, but I don’t mind saying that Malick’s movies are good for the soul.

Badlands was Malick’s first feature, premiering in 1973. It was also Martin Sheen’s feature debut, though he was an experienced TV actor. Sheen plays Kit, a twenty-five year old garbage collector in a small South Dakota town. One day after work, he sees fifteen year old Holly (Sissy Spacek) hanging out in her front yard. Kit is instantly smitten with her.

Holly blows him off at first but she eventually warms to him and they begin an affair. Spacek, who was actually in her early twenties when she filmed the movie, is a strange kind of beauty. She’s twig-thin and awkward. Far from what you might call a typical Hollywood beauy. Which is the point. She’s an attractive girl, but not so much that she’s realistically out of Kit’s league.

Kit and Holly have to hide their affair from her possessive father (Warren Oates), who hasn’t really wanted anything to do with his daughter since his wife died. They mostly hang out in the woods, near a stream. Holly does most of the talking. Kit’s a quiet man, the classic Western man-of-few-words.

Holly’s father soon finds out about the affair and, as punishment, he shoots her dog while she watches. The scene evokes such a primal sadness. It’s almost hard to breathe watching such casual cruelty. A little later, there’s a scene that evokes an opposite emotional reaction. Kit, in an effort to prove his devotion to Holly, writes a note that basically says he’ll never leave her and then puts it in a basket and sends it skyward, attached to a red balloon. We watch the thing rise, aware, perhaps, that it will eventually fall earthward again. It’s moments like these where we realize that Malick is capable of taking us to the greatest of emotional depths. He doesn’t take sides, emphasizing one particular emotional state over another. He wants us to experience the world organically, to see good and evil as parts of a whole.

In a field on the outskirts of town, Kit confronts Holly’s father. Both men have few words to say to each other and end their conversation in stalemate. Holly’s father still forbids Kit from seeing his daughter and Kit is still determined to be with her. A little while later, Kit is in Holly’s room, packing a suitcase for her. Holly and her father come home and the inevitable confrontation begins. Kit shows Holly’s father that he’s armed and tells him that if he tries to call the police, he’ll be shot. With fear in his eyes, the father heads toward the phone and Kit fires his gun, killing him.

It’s not a cold blooded killing. Kit has no feelings either way about Holly’s father. If he had allowed Holly to continue to see Kit, there wouldn’t have been any problems. But Kit’s a man ruled by his desires. He doesn’t think things through because he isn’t capable of it. He’s simply doing what he feels like he has to.

After her father is killed, it becomes clear just how young and vulnerable Holly is. She believes that she’s in love with Kit, sure, but she’s only fifteen. While the affair means everything to Kit, for Holly it’s really just a kind of puppy love. But with her father dead, Holly has virtually no choice but to leave town with Kit. She is, after all, still a kid. She needs a protector.

After grabbing a few supplies from the house, Kit burns it down. The pair then go by Holly’s school to get some of her books and head out of town in Kit’s car. They end up building a weird sort of Robinson Crusoe setup in the woods. They build an elaborate tree fort to live in. Holly reads her schoolbooks aloud to Kit, looks at old pictures and tends to their stolen chickens. They live in a strange kind of wilderness domestic setup. You get the feeling that this is Kit’s version of paradise: he’s got his girl, he doesn’t have to talk much, he loafs around. But eventually some bounty hunters find them and Kit kills all four of them. Holly and Kit go back on the run. Kit leaves bodies behind at virtually every stop they make.

Kit isn’t an idealist. But he isn’t a nihilist either. What he is, then, is someone not quite human, or, even better, all too human. He’s a bundle of nerves and instincts. Killing doesn’t bother him, but he doesn’t get a kick out of it either. It’s just that Holly has become everything to him, his only desire. Anything that isn’t She is periphery. Other people are barely visible to Kit, that is, until he sees them as a threat to his only desire.

And while Holly is just as inarticulate as Kit, she can immediately be forgiven. She’s fifteen years old, just a child. As she narrates the movie in voice over, we become all too aware of her innocence and naiveté. Father is replaced by lover as authority figure. Both situations are equally suffocating. She simply cannot get away from men who want to control her, or, even worse, to own her. Her narration is frank but jumbled, as we might expect.

The film is stunningly photographed. Malick uses mostly wide and medium shots. Kit and Holly are small-statured next to the natural surroundings that envelop them. After all, the natural world will continue with or without them and is indeed oblivious to their existence. Seen this way, nature as a whole is really the main character of the film.

Badlands is ultimately a story about the pettiness of human desire once it’s put to the metaphysical test. The movie might overwhelm you.