The Death of Books and the Reading Renaissance

Written by: Beth Woodward, CC2K Books Editor

Paper books are dying.

Paper books are dying.

Maybe it’s not quite time to bring the priest in to administer the Last Rites yet, but I’d definitely pay a last visit and make sure you’re still written into the will. That is to say, paper books won’t be disappearing tomorrow. I doubt they’ll ever disappear entirely. But I’d estimate that within the next 10-20 years, most people will look at paper books the way they look at record players or spinning jennys: interesting relics of a bygone era.

You’d think, as an avid reader, aspiring novelist, and hell, as CC2K’s Book Editor, I’d be a little more upset about this. But I’m not. To be honest, I’m not terribly attached to the book. I’m attached to reading, and I’m attached to stories. But the book is just the form used to convey those stories that I love to read. And reading and stories are not going anywhere. In fact, I think we’re on the cusp of a reading renaissance.

Now, this may seem counterintuitive, especially in light of Barnes & Noble’s recent announcement that it will be closing at least 20 stores a year for the next decade. Plus, e-book sales grew only 34 percent between August 2011 and August 2012, which may be signaling that the growth of the e-book industry is stagnating. For the previous four years, e-book purchases had doubled every year, and dedicated e-reader sales have slowed as well.

But I don’t buy it.

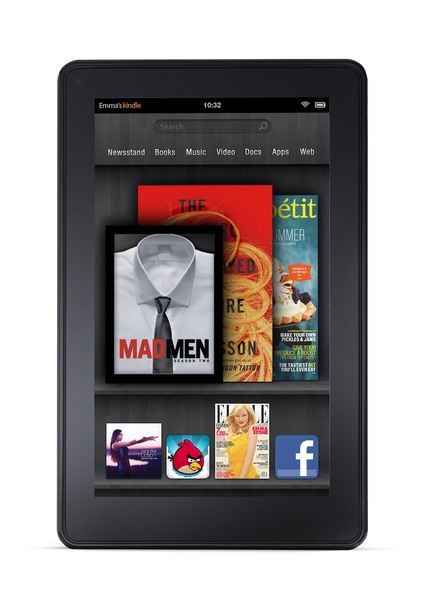

It makes sense that the rate of e-book purchases would now slow: the e-reader early adopters tended to be more avid readers than the ones who waited until e-reader price points fell below $100. It also makes sense that the sales of dedicated e-readers would slow with the introduction of tablets, which have more features and capabilities than dedicated e-readers. Of course a tablet would be more appealing than a dedicated e-reader to a casual reader. I also think we’ve hit the point in the e-book industry where growth is just naturally slowing down. Kindles and Nooks are no longer the new, cool toys they were three or four years ago. But the industry will continue to grow, albeit not as quickly as before. (Plus, I think there are a few more changes the publishing and e-reader industries need to make before they can reach full market saturation, but I’ll get to that later.)

Ever since I was a kid, I’ve seen collective hand-wringing—from teachers, from parents, from dedicated bibliophiles—about the death of the book. They’d lament that people, kids especially, just weren’t reading anymore. But why should they? When television and video games and the internet were instantly accessible—and always offering new content—going to the library or the bookstore to get a book just wasn’t as convenient or easy.

When Amazon entered the scene, with its quick delivery service, we could get books delivered to us…within days. But still, not instant. E-readers changed all that. Within seconds, we could order a book online and have it delivered to our e-readers electronically. What we’re seeing within the book industry is the same thing we started seeing within the movie industry a few years ago: movie rental stores like Blockbuster got pushed out of business by movie delivery services like Netflix, which then found its next-day delivery challenged by the ease and accessibility of downloadable and instant-streaming movies. And while I think this will continue to change the business model of the movie industry, I don’t think movies are going anywhere.

It’s the same for reading. Paper books may be dying, but reading is being brought into the 21st century.

For better or worse, we have become an instant gratification society. Why would we put in effort for our entertainment options when we can have other options more quickly and easily? I am no exception to this. I must confess, my reading had decreased significantly before I received my Kindle in 2009. I worked all day, and it was an effort to get to the bookstore or library. When I’d finally get there, I’d often buy several books at a time—many of which I’d end up never reading because I’d lose interest, or forget about them, by the time I was done the first one. This habit ended up being entirely too hard on my pocketbook, so I cut back. Plus, it was just way easier and faster to turn on the television than to go looking for books through the endless aisles of Barnes & Noble or the library. (I never have figured out the damn Dewey Decimal System.) Not to mention the fact that I have a terrible habit of forgetting to return library books on time. I always get them back eventually, but I’ve been known to harbor overdue balances at Arlington County Library for years at a time.

Owning a Kindle changed all that for me. I usually only buy one book at a time, but it’s usually a book I want to read right now. Before I got a Kindle, I’d estimate that my non-read book read was about 50-60% (in other words, I didn’t read 50-60% of the books I bought). Now, it’s probably about 5%. I also buy, and read, a much greater number of books. From what I have heard anecdotally, my experience is pretty similar to that of other e-book readers.

The growing prevalence of e-books is not going to turn non-readers into readers. But it will allow reading to compete as a recreational activity on the same playing field as television, video games, and internet usage.

As for more practical usages: I suspect more and more textbooks will be published electronically in the next several years. Back when I was in college, I purchased hundreds of dollars worth of textbooks every semester. They were heavy, marked with other students’ notes, and I often forgot to take them back to the bookstore for buyback at the end of the semester. E-textbooks eliminate both the annoying notes from previous students and the heaviness. (The price gouging, I suspect, won’t be so easy to eliminate, unfortunately.)

Many people do a great deal of reading while on vacation—including me. I am an extraordinarily fast reader, so on a cross-country flight I can usually get through one book, maybe two. (Don’t even get me started on international flights.) I used to have a system: I’d bring three books on vacation with me. By the return flight, I’d be through at least two of them. I’d put the books I’d read in my suitcase, and buy one or two new ones for my carry-on. A carry-on bag holding 2-3 books gets very heavy, very fast, especially if they’re hardcover, and I can’t tell you how many times I’d come home from vacations with an aching back and shoulders. Not a problem anymore. My Kindle can hold my entire library, and the only other thing I keep in my carry-on bag are Teddy Grahams and a toothbrush—neither of which are as heavy as books.

Newer e-readers and tablets allow readers to get e-books with graphics and pictures—a feat that would not have been possible on earlier, black-and-white e-readers. Suddenly, picture books, cookbooks, and graphic novels are easy and convenient to read electronically, as well. Not to mention that the lack of printing costs now makes stand-alone novellas and short stories a marketable reality.

Now, as I mentioned earlier, the e-book industry isn’t perfect yet, and I think both publishers and e-reader manufacturers have some work to do before e-books can dominate the industry entirely. This includes:

–Enabling the lending functionality on all books. Want to know one big advantage a paper book still has over an e-book? If my friend Betty Bookworm wants to borrow my paper book, I can loan it to her with no problem. Not so much with e-books. The lending functionality is disabled for many of the books on my Kindle—a restriction that I suspect comes from the publishers, not Amazon. Furthermore, although some publishers make e-books available for lending through public libraries, many still do not. Even with those that do, the lending policies seem to be very restrictive and cost-prohibitive for libraries. Having e-book lending capabilities is great, but not so much if you can’t get the book you want.

–Deciding upon a standardized format for e-books, or making all formats readable on all readers. I’ve got a Kindle. But if I ever decide to buy a Nook, I’m pretty much shit out of luck. Well, not totally. There is a way to convert Kindle books to Nook format, but it involves both converting the format and removing the Kindle DRM—an access control technology used to limit digital content distribution after sale. (It’s what prevents you from accessing the book on more than the allotted number of devices, for example.) I’m not entirely sure, but I think removing the DRM is of dubious legality.

I have hundreds of books in my Kindle library. There’s no way I’d be taking those steps for all of them. Not to mention the fact that, for less technologically savvy readers, the process would be difficult or impossible. One should be able to hook up an old Kindle to a new Nook and get the books to transfer automatically. Not so much.

(On a related note: maybe I shouldn’t be admitting this, but I’m not sure how I feel about DRM. On the one hand, since every e-reader’s DRM is different, it prevents you from being able to transfer from one reader to a different type of reader easily. On the other hand, without some type of restriction technology, what’s to prevent me from sharing said e-book with 900 of my closest friends? On the third hand, DRM is, apparently, relatively easy to remove—and I’ve now run out of hands. I’m open to discussion on this one.)

–Publishers need to figure out reasonable, and realistic, price points. Now this message is for publishers more than readers. For readers, it’s good news: the growth of e-books has allowed smaller presses to thrive, and has made self-publishing an attainable reality for many authors. Many of these e-books are priced lower than e-books published by big publishers. If you see two e-books, one for $2.99 and one for $9.99, which one are you going to buy? Assuming neither are by authors you’re already attached to, and they both look equally interesting, you’ll probably go for the $2.99 book. Publishers really need to look at their business models and pricing points in order to remain viable. (For the record, I think the demise of agency pricing—the e-book pricing model that allowed publishers, rather than retailers, to determine the price of books—could ultimately be a good thing for publishers.

The book industry is in upheaval right now—much like the music industry was a decade and a half ago. But I think ultimately, this will be a really, really good thing for readers.

Welcome to the 21st century, books. I think you’ll like it here.