The Cult of Jane Austen

Written by: Beth Woodward, CC2K Books Editor

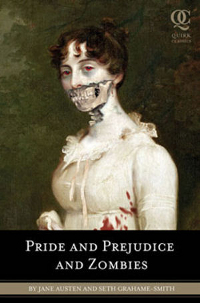

When i first wrote this article in 2009, the newly published Pride and Predjudice and Zombies was all the rage. I read the book. I found it to be more hype than substance (though I think the powers that be are making a movie out of it, anyway), and the frenzy died down after a couple of months.

But Austen fever doesn’t seem to be going anywhere. Every time I look around, I see another Austen-inspired book, movie, or television series. In fact, I think you could make a solid argument that Jane Austen is indirectly responsible for a good percentage of our historical romances today.

What’s up with Jane Austen lately? Back when I was in high school and reading Pride and Prejudice, people were looking at me like I was out of my mind. Austen was boring. Austen was prudish. Austen was austere. Who would read Jane Austen when they could be reading Hemingway or Vonnegut or Salinger?

But all this begin to change a few years ago, and Austen suddenly became…cool. Suddenly, Jane Austen is everywhere. From movies (Becoming Jane, Bride and Prejudice) to books (Jane Austen Book Club, Mr. Darcy Takes a Wife), suddenly everyone seems to be appropriating Austen.

(Honestly, I blame Colin Firth for a lot of this. Ever since the BBC adaption of Pride and Prejudice was released in 1995, Austen fever has slowly been infusing the culture. I guess it was something about seeing Firth come out of that lake, dripping wet, that really re-launched Austen mania in popular culture.)

The latest entry into the cult of Jane Austen is Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, adapted from the classic Austen novel by Seth Grahame-Smith. It takes the classic romance between Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy and infuses it with “unmentionables”: brain-hungry zombies. Elizabeth and Darcy are both accomplished zombie slayers, rivaled perhaps only by Lady Catherine de Bourgh. The militia regiment that Wickham is a part of is stationed near Hertfordshire to assist in the ongoing human vs. zombie battle. And Charlotte marries the pompous Mr. Collins not because she is worried about becoming an old maid, but because she has been secretly infected with the “plague” of zombiedom.

I expected the book to be funnier than it was, but the novelty of the concept wore off after about the first 50 pages. And unlike other entries into the Cult of Jane Austen, this one seems to be making fun of Austen rather than paying tribute to her. The book turns Elizabeth into a cross between the lively, intelligence woman of Austen’s original and a complete sociopath. And Darcy is the kind of guy who maims old enemies rather than belittle them. It’s almost as if Grahame-Smith is saying that in order to make Austen readable, you have to add zombies.

But I guess that my main problem with Pride and Prejudice and Zombies is also my problem with the rest of the Cult of Jane Austen: the more we’re inundated with media inspired by Austen, the farther we get from Austen herself.

Thing is, I like Jane Austen’s novels. I’ve read almost all of them, most of them multiple times. I like the lively banter between Darcy and Elizabeth. I like the themes of love and loss and finding love again in Persuasion. I love the strong sisterly bond between Elinor and Marianne Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility. I love the youthful naiveté of the protagonist in Emma. I love that Austen’s novels are so subtly witty that the difference between realistic characters and social satire is often ambiguous. And most of all—and I think believers in the Cult of Jane Austen often forget this—I love that Austen shows that love is not always the perfect, romantic fantasy we want it to be. In fact, many of Austen’s books—Sense and Sensibility, Emma, Mansfield Park, among others—show characters who must give up those romantic fantasies before they can find true, lasting love.

So I guess I really can’t complain about the Cult of Jane Austen too much—after all, anything that brings more attention to Austen’s novels can’t be a bad thing. But I think a lot of the worshippers dreaming of their own Mr. Darcy are missing the point. Austen’s books are about imperfect romance, filled with imperfect people. Austen’s characters endure precisely because they are not fantasies—though the sight of Colin Firth in a wet shirt may obscure that for some.

I guess what it comes down to is this: many of the Cult of Jane Austen adaptations take Austen’s ideas—and, in the case of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, most of her prose—and turn them into something different. But you can’t expect that you’ll improve upon Austen. These Cult of Jane Austen adaptations are, in most cases, nothing more than fan fiction.

So if you’re in the mood to write a romance, create your own, and leave Austen alone for modern readers to find on their own. Jane Austen and her novels have endured for more than two centuries now; she does not need a cult for readers to find her.