Sundance Review: ‘Native Son’ marries punk and the words of Richard Wright

Written by: Adriana Gomez-Weston, CC2K Staff Writer

In his directorial debut, Rashid Johnson has taken on an ambitious feat with his adaptation of the renowned novel, “Native Son”. A collaborative effort between HBO Films and A24, the film of the same name is the latest in a string of Sundance premieres from the critically-acclaimed industry heavyweights.

Not the first adaptation of Richard Wright’s work, Johnson’s film manages to pay homage to the source material, but stands on its own. Over the decades, Wright’s novel has withstood the test of time, as its message still stands tall in 2019. Racism and classism are still deeply ingrained into our society, and the latest adaptation of Native Son proves that not much has changed in nearly 80 years. An update from the 1940 novel, Johnson sets his interpretation against the background of modern Chicago. Native Son takes several creative liberties, primarily infusing punk with the words of Richard Wright.

Rashid Johnson and screenwriter Suzan-Lori Parks have adapted the film for today’s social and political climate. Drawing from the experiences of the modern black man, and the horrors of the “post-racial” society we live in, Native Son pulls no punches. It’s a theatrical experience that stimulates the emotions and leaves audiences gasping for air. Those that are acquainted with the novel are familiar with the bitter story, but will be greeted with a different conclusion than in the past.

Bigger (Big) Thomas (Ashton Sanders) is a rebellious freethinker who is struggling to figure out his path in life. Encouraged by his family to do better, Big takes a job as a personal driver for the affluent Dalton family. While the job isn’t ideal, it offers Big a chance at financial stability and upward mobility. The majority of Big’s job constitutes driving Henry Dalton’s (Bill Camp) spoiled, but well-meaning daughter Mary (Margaret Qualley), and performing menial tasks such as loading coals into an old furnace.

Big caters to Mary’s every whim by driving her to school, to visit her boyfriend Jan (Nick Robinson), and escorts her to wild parties. Eager to keep his job, Big attempts to keep Mary out of trouble. However, Big manages to fall into a predicament that stacks the cards against him. At that point, the scales are tipped and Big’s flawed character is exposed for what it really is. How should we react to the circumstances? It’s up to the audiences to decide.

Native Son is an atmospheric slow burn that prioritizes the actions and thoughts of Bigger (Big) Thomas.

Big appears present, but at the same time floats through his circumstances. Ashton Sanders gives a powerhouse performance as Big, giving every fiber of his being into the role. Sanders has a mesmerizing screen presence, and garners an audience response no matter what he does. His performance is complemented by Kiki Layne’s Bessie. Still a fresh face on the screen, Layne’s second film is a step in the right direction for her burgeoning career. The entirety of the cast of Native Son is solid, with impressive supporting performances by Margaret Qualley, Nick Robinson, Sanaa Lathan, Bill Camp, and Elizabeth Marvel.

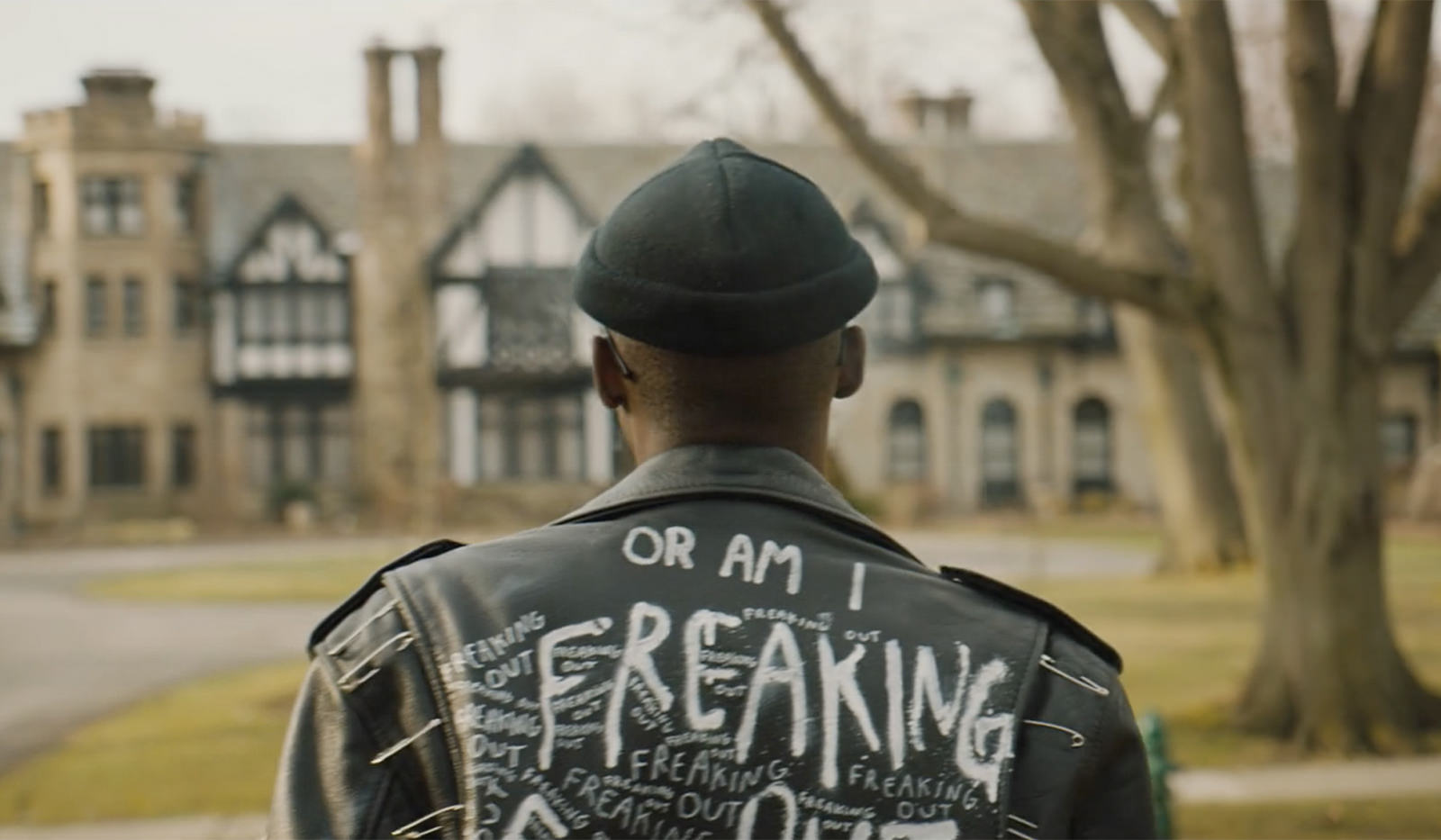

Brimming with a distinct, bold style, the imagery of Native Son wows. Every frame, every closeup shot pushes the narrative of the film’s leads. Big’s green hair, anarchic attire, and ringed fingers are sure to influence audience-goers and trendsetters. The look and feel of Native Son flows like Richard Wright’s words, and lingers in the mind.

Native Son is bound to strike a chord with audiences, and is likely to remain in the public consciousness. It’s a hard pill to swallow, but its not meant to make its audience comfortable. It’s there to create a discussion about human nature, and the capacity to become complacent in our own circumstances. As a comparison, the critically-acclaimed If Beale Street Could Talk provides a similar statement, but in a more palatable way. The Black Man has been painted as “bad” for generations, and circumstances often lend to that. As both films (and novels) indicate, its up to the the man whether he wants to actively change his narrative, or allow himself to become a part of it. How will viewers take to Big’s plight? Native Son leaves a bitter taste, and goes out with a dark statement.

The biggest draw in Native Son is how you perceive it, and there’s no one way to do so. What did you see? And how did you feel when you saw it?

“The only thing worse than being blind, is having sight with no vision.”