Stacia Kane’s Downside Ghosts Series and the Damaged Heroine

Written by: Beth Woodward, CC2K Books Editor

A little over a year ago, I was revising a novel I had been working on. I really liked the story, but I worried that potential readers would have a hard time accepting my heroine. See, she’s screwed up. Really, really screwed up. I would go as far as to say that she’s damaged.

A little over a year ago, I was revising a novel I had been working on. I really liked the story, but I worried that potential readers would have a hard time accepting my heroine. See, she’s screwed up. Really, really screwed up. I would go as far as to say that she’s damaged.

Fact is, there aren’t a lot of damaged heroines in literature. There are flawed heroines, which is great. Obviously, we don’t want our characters to be perfect. But damaged is a whole different threshold. “Damaged” is someone who repeatedly does unhealthy, destructive things. “Damaged” is someone whose sense of self-worth is permanently degraded by the things she’s done or experienced. “Damaged” is someone so far outside of society’s standards for normally and acceptably flawed that we often have to do some mental gymnastics to understand their thoughts and morality—let alone sympathize with them. (And some of them, quite frankly, are just not sympathetic.)

I can think of several male characters off the top of my head who fit this description. Humbert Humbert. Holden Caulfield. Hannibal Lecter. The Phantom of the Opera. Dexter. Several of the male leads in J.R. Ward’s Black Dagger Brotherhood series. Some of these characters are sympathetic, and some are not. But their morals, behavior, and/or psyches are so far outside of society’s norms that, if we met them in real life and knew who and what they were, we’d more than likely walk in the other direction.

But I couldn’t think of a female equivalent. Female characters almost always seem to fall into that “acceptably flawed” category—if they don’t fall into that “just too damn perfect” category, that is. It’s almost as if we’re afraid that, if a female character deviates too far from societal norms, she’ll no longer be someone the audience wants to read about. There’s also the question of sympathy. Several of the male characters listed above are unsympathetic characters to most or all readers. (Humbert Humbert comes to mind as particularly reprehensible.) But others are sympathetic on some level, even when we don’t agree with their actions, like Dexter. (Full disclosure: my knowledge of the character comes from the first few seasons of the television show, not the original Jeff Lindsay book series.) Dexter is a serial killers, a sociopath. But he only kills other killers. He seems to feel some attachment to his family and friends—in his own, highly unusual way. And his pathology was caused partially because of a violent childhood trauma that permanently etched into his memory, and partially because of a loving but rather misguided adoptive father who didn’t know how to deal with his damaged son. Would a female character exhibiting the same type of behavior be regarded as somewhat sympathetic—or just evil? Can readers enjoy a book about a female character they can’t sympathize with?

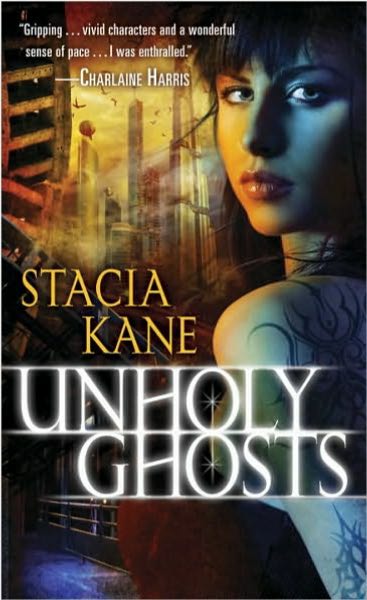

Then last March, I read Stacia Kane’s brilliant Downside Ghosts series. (Unholy Ghosts, Unholy Magic, and City of Ghosts are the first three. The fourth book, Sacrificial Magic, will be released on Tuesday.) I was completely awestruck. For the first time, I was reading about a heroine who was decidedly damaged—and it was fantastic!

Chess Putnam works as a witch for the Church of Real Truth, which has ruled the country since the government fell. In Chess’s world, ghosts are real—and have an unfortunate tendency to attack the living. The Church promises to protect people from ghosts, which is how Chess got her job. Chess is also a drug addict. Orphaned as an infant, passed from one abusive foster home to another, Chess uses the drugs to chase away the demons in her head. She’s incredibly self-destructive and self-loathing, and her addiction often gets her into trouble. (In fact, it’s the whole catalyst for the plot to Unholy Ghosts.) Yet in spite of all this you root for her. She takes pride in her job and tries to do it well. She does her best to help other people. And when she develops a tenuous relationship with Terrible, a local gang enforcer, you want her to succeed, even though she does her best to destroy it every chance she gets. Yes, she can be thoughtless and unintentionally hurtful to the people who care about her, especially Terrible. But through her eyes, we can see how this is motivated by fear and a lack of self-esteem, not selfishness. It’s hard to like Chess all the time. But it’s impossible—for me, at least—not to feel for her.

I fell in love with this series partially because of its willingness to explore the dark, scary places of the human soul, and I applaud Kane for taking the risk of going there with a female character. That’s not to say that every reader will embrace such a female character, a topic I already explored here a few months ago. But as someone who was immediately sucked into this series, I can say that Kane has managed the difficult balancing act of making Chess both damaged and relatable.

Why is that? I’ve never been addicted to drugs. (Hell, I’ve never even tried any.) I didn’t have an abusive childhood. I’ve certainly never hunted ghosts. But I have felt worthless. I have been self-destructive. I have done my best to push everyone away. It’s not the way I feel now, but I was there, and I remember it all too well.

Maybe that’s the thing about damaged characters: at some point in our lives, don’t we all become a little bit damaged? Chess’s experience is very particular, but there’s a certain universality to it. I sympathize with Chess because I’ve had to overcome my own demons, and in reading about Chess’s struggle I feel connected, like someone else has felt the way I once felt.

I suspect that’s why the heroine of my own novel came out the way she did: in some unconscious way, I brought my own battles to the page. I just hope that more authors take the risk to go down that road, because I don’t think I’m the only woman who can, on some level, relate to a damaged heroine.