Spike Lee’s The Inside Man

Written by: Lance Carmichael, CC2K Staff Writer

Spike Lee Joints and the Search for the Greatest Working Actor

Inside Man Sparks Blood Feud Between Denzel Washington and Philip Seymour Hoffman

Spike Lee Joints come in all shapes and sizes, and you never know whether you’re going to enjoy it until you bite into it. You’ve got your Strident Social Message Films, some good (Bamboozled, He Got Game), some bad (She Hate Me), and some great (Do the Right Thing). You’ve got your History films, which he takes great care in choosing incendiary, cinematic topics: this has led to what I think is his best film (Malcolm X) and one of his most disappointing (Summer of Sam: seemed like can’t-miss slam-dunk source materal for Spike, ended up being eminently forgettable). You’ve even got straight-up documentaries (Four Little Girls, The Original Kings of Comedy), none of which I’ve seen, and you probably haven’t, either.

Spike Lee Joints come in all shapes and sizes, and you never know whether you’re going to enjoy it until you bite into it. You’ve got your Strident Social Message Films, some good (Bamboozled, He Got Game), some bad (She Hate Me), and some great (Do the Right Thing). You’ve got your History films, which he takes great care in choosing incendiary, cinematic topics: this has led to what I think is his best film (Malcolm X) and one of his most disappointing (Summer of Sam: seemed like can’t-miss slam-dunk source materal for Spike, ended up being eminently forgettable). You’ve even got straight-up documentaries (Four Little Girls, The Original Kings of Comedy), none of which I’ve seen, and you probably haven’t, either.

Then there’s the kind of Joint that finds our resident angry artiste working in genre films. Ah, bliss. Is there anything better than the combination of a talented American director working on those sturdy warhorses of Hollywood genre? Sure, oftentimes it’s the harbinger of a wholesale career sellout, the end of the interesting era of an artist’s career. But sometimes it means a reinvigoration. Perhaps the director is tapped out when it comes to generating complete movies on his own. Maybe the old plot idea well is running dry. But the calculating, encompassing artistic intelligence is still there.

Perhaps that is the case with one Shelton Jackson, AKA Spike. The last two Joints Spike had screenwriting credit on were Bamboozled and She Hate Me, and they might be a sign of ever-diminishing returns on his writing. Bamboozled couldn’t really be called a success, but at least it was thought-provoking. Its subject matter (essentially, corporate co-optation of black culture and Blackface in all its multifarious forms) is something we rarely see getting serious, extended treatment in feature films, so for that we can be grateful, and the filmmaking was restless and inspired. It was just perhaps a bit too self-righteous and angry to passably be labeled an “entertainment,” and feature films, on some level, have to achieve that. I’m sorry, they just do. She Hate Me was an incoherent, poorly executed mess, an ambitious film in search of a political theme. Spike couldn’t seem to find what he wanted to rail against, so each scene picked a target out for itself and strangled all the life out of it. She Hate Me did not seem the product of a pleasant man.

Thank god Spike’s not above directing someone else’s screenplay, then, because two out of Spike’s last three Joints (with She Hate Me sandwiched uncomfortably in the middle) are solid genre films farmed out to fresher, first-time writers. 25th Hour crackled with an irresistible plot-line (it follows a repentant drug dealer on the last 24 hours before he begins serving an extended jail sentence), and provided a firm foundation on which to build three marvelous performances (by Edward Norton, Philip Seymour Hoffman, and Barry Pepper…three white guys). Because the genre storyline was so tight, such a perfect drama-creating machine, Spike got to settle down and concentrate on building up and examining three very different, very multi-faceted characters. 25th Hour celebrated the human, letting the social milieu stream in through their eyes. This was something She Hate Me and Bamboozled did the other way around: starting with the social setting and showing us three character’s through ITS cold, inhuman eyes. That, I submit, was why those Joints felt, in the end, to be failures, while 25th Hour was a triumph. It’s a cliché, but it true: make your characters real, firmly establish complex human relations between them, put them in an interesting setting, and you basically can’t fuck up.

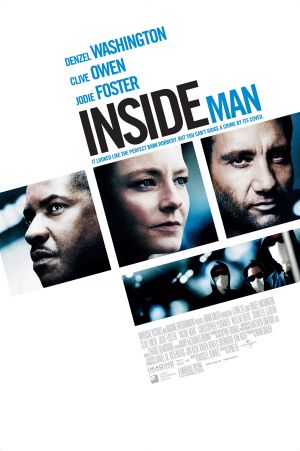

Inside Man follows in the triumphant tradition of 25th Hour rather than She Hate Me, I’m proud to tell you. By now, you probably know the broad strokes: it’s a heist movie where Clive Owen plays the bank robber with a mysterious plan he keeps pointing out to us is ingenious; Denzel Washington plays the hostage negotiator; and Jodie Foster plays some sort of NYC power player serving at the leisure of the bank’s owner, man-with-a-past Christopher Plummer.

This is Denzel Washington’s movie. Oh, sure, it’s entertaining to watch Clive Owens’ heist plot unfold, but it’s a lot of smoke and noise; it’s a pretty simple heist plot, really, and I often felt like Spike and the screenwriter were drawing it out a bit too long, giving its cleverness a little too much credit. Jodie Foster’s character and performance are a little hard to stomach, straining both credibility and my patience for smug assholes. So what makes Inside Man work so well?

Folks, once again, it’s Denzel who holds it all together. He’s in Training Day mode here; though he’s the good guy, he’s got that swagger that Denzel possesses in a higher concentration than any other human on the planet. Training Day was a great movie with Denzel, but would have been a shitty movie with probably anyone else in his role. With Inside Man, once again he picks up the entire movie and carries it on his broad, charismatic shoulders. He’s almost entering De Niro in the 70s territory here; technically, De Niro isn’t all that great an actor. He really can’t do accents, and he only has one mode: intensity. But that intensity and the out-and-out coolness of his presence burned so brightly that he’s (rightly) regarded as one of the greatest, if not the greatest, screen performers of all time–mostly based on his work in the 70s.

Denzel is the same animal. He’s not all that versatile (watch him try to stretch his acting muscles to play a twitching, stuttering weakling in the Manchurian Candidate remake; it’s uncomfortable to watch (and not in a good way)), but he possesses De Niro’s intensity in an almost equal measure. When Denzel is on-screen, you cannot take your eyes off him. It is absolutely, categorically impossible. It’s probably only his bad luck to have been born unto an era where there really aren’t that many great roles to go around that he’s not regarded in, say, the class of a De Niro, Pacino, Nicholson, or Hoffman (Dustin…although Philip Seymour is approaching this acting Valhalla as well). How many great roles does it take to get in these guys’ class? By my count, Denzel’s only been fortunate enough to snag two: Malcolm X and Training Day. This is not to say he’s hasn’t turned in any other great performances, or that he hasn’t been in other very good movies. But Malcolm X and Training Day are movies where the only reaction to his performance is silent awe.

Comparing this to two of the biggest heavies from the 70s is enlightening: Pacino turned in four Pantheon Performances (The Godfather, The Godfather Part 2, Dog Day Afternoon, and Scarface) as well seven tour de force turns that are pieces of genius but don’t quite reach those same blessed heights, for one reason or another (Glengarry Glen Ross (ensemble piece, not really his movie), Heat (great performance, but too over-the-top for some people’s tastes (not mine, but I can see their points)), Donnie Brascoe (in the end, too minor of a film to consider his performance a classic), Any Given Sunday (still too much “Hoo-ha!”), Angels in America (again, an ensemble piece, but contains scenes that hold up next to anything else he’s ever done), The Insider (still too much “Hoo-ha!,” plus he only turned in the second-best performance in the movie…Russell Crowe outshone him, and to make the Pantheon, you have to own the movie), and Carlito’s Way). De Niro’s turned in a whopping eight of these performances, by my count (Mean Streets, The Godfather Part 2, Taxi Driver, The Deer Hunter, Raging Bull, The King of Comedy, Casino and Heat). He was also in–but not so central to the success of–two other masterpieces (Brazil and Goodfellas), but then again, he was the go-to guy for perhaps the greatest movie director of all time, Harold Ramis (I mean Martin Scorsese).

Most of these roles came during the 70s, when masterpieces were showing up in local theaters every couple weeks, so it’s an unfair comparison, like talking about Wilt Chamberlain’s 100 points in a game record, set in a time when it was much easier to do that kind of thing. But then again…

Let’s look at what Philip Seymour Hoffman’s done. When I think of him in the following movies he’s been in, a bright, warm bulb of remembrance pops into my head, memorable roles that are unimaginable with anyone else in them: Boogie Nights, The Big Lebowski, Happiness, Magnolia, and Capote). The thing to remember, though, is that all of these roles but one were fairly small. Hoffman is a character actor, through and through, not a lead–not even by the generous standards of the 70s. Hoffman probably shouldn’t play the lead except in those rare cases like Capote, where what’s essential a character actor’s part gets spotlighted as the lead. It’s worth noting that his namesake, Dustin, is a similar type of actor. Like Philip Seymour, Dustin specializes in puny, weak men (see The Graduate, Straw Dogs, Marathon Man) or freaks (Lenny, Rain Man). These are essentially the character parts that are almost always more interesting than lead parts, but in Dustin Hoffman’s case, they were the leads in these particular movies. These movies only got made because Hoffman (improbably) was a big movie star, and it was a more adventuresome era, artistically. Philip Seymour Hoffman’s not so big, At least yet.

Regardless, Hoffman and Washington–the two guys I would nominate as the greatest actors of our present time–represent totally different ends of the male acting profession. Philip Seymour is the greatest character actor around, but Denzel’s the greatest lead. There’s really no overlap between these two (Can you possibly imagine a role they both could play?) Philip Seymour Hoffman’s work will always be more colorful than Denzel’s, but in the end, when Denzel’s on-screen, and he’s got an interesting enough role, no one commands our attention so forcefully as this man. When I watch Denzel, I’m half-terrified of him, like I’m a young man staring up in awe at my father. That’s a movie star. Who knows what he would have been capable of if he didn’t have to work with Jerry Bruckheimer to maintain his cred as a leading man.