Soulmates and Free Will: A Debate About The Time-Traveler’s Wife

Written by: The CinCitizens

Tony Lazlo responds:

Beth, you make a lot of good points. I hadn’t considered the possibility that the galoshes belonged to Alba and her children, but more important, I hadn’t even considered Clare’s choices when it came to the letter. You’re also right to praise Henry and Clare’s tenacity, strength and hard work in maintaining their relationship.

I also completely forgot that Gomez was married with kids when he came on to Clare. I concede that Gomez might not have been the best choice for her, but I stand by my previous argument: That Clare should have moved on.

But let’s talk free will and determinism. It’s tough to debate these issues in the context of a book like this, because Niffenegger – by virtue of her central device – has already made that choice for us. In the reality of her book, free will does not exist. It’s a deterministic universe.

That choice alone adds some tension to even considering Clare’s (or anyone’s) ability to make choices in this world, but my point here isn’t to bust your chops for some kind of goofy argumentative contradiction but again to criticize Niffenegger for her endorsement of such behavior. Now, this raises a weird point: How can I criticize Niffenegger for how she portrays characters in a time-travel story? Isn’t her scenario too far outside the boundaries of reality to be relevant? (Please call shenanigans on me in the forums if that’s a straw man.)

I say it isn’t. I maintain that Henry made a morally horrifying choice that is analogous to any choice a real-world person would make to interfere with the future of someone else. Examples that spring to mind range from (on the extreme side) a bitter deathbed condemnation to (on the mild side) a psyche-out delivered to a co-worker as they walk into an important meeting.

I say it isn’t. I maintain that Henry made a morally horrifying choice that is analogous to any choice a real-world person would make to interfere with the future of someone else. Examples that spring to mind range from (on the extreme side) a bitter deathbed condemnation to (on the mild side) a psyche-out delivered to a co-worker as they walk into an important meeting.

And let me expand on these examples:

• On the extreme side, try to imagine if a dying parent experienced a moment of weakness on their deathbed and let fly with something bitter like “I never loved you” or “I never believed in you.” If that sounds outlandish, consider how easy it would be for a dying person to find moral security in telling such unpleasant truths on their deathbed – they’re dying, after all, so why not tell the truth? Hell, deathbed admissions are even admissible in court sometimes.

• On the mild side, try to imagine if an employee knew that a co-worker was having trouble with his girlfriend, and right before an important meeting that can’t be delayed, that employee told his co-worker that his girlfriend called with bad news.

Can you see what I’m getting at? In certain situations, we have an obligation to keep our mouths shut or to otherwise tell white lies so that friends and loved ones can function normally. Sometimes the truth really isn’t necessary.

Let’s bring this back to Niffenegger’s novel and a point I raised earlier – that in a deterministic universe, why even discuss Clare’s choices? Beth, you nailed this one: Even in the deterministic universe Niffenegger creates, Clare had a choice once Henry was gone. As long as she doesn’t know the future, then for all intents and purposes, she has free will.

And Henry damn well knew it.

Even within the fantastic circumstances of Niffenegger’s novel, Henry had a real-world choice to make: He could let Clare live her life, or he could sabotage her. He chose to sabotage her. But that’s not how Niffenegger saw it.

I don’t mind that the author includes such a choice, but I mind that she assigns the choice to her hero, and she tacitly endorses both the action and Clare’s reaction to it. Again, I submit that Niffenegger finds a treacly, drippy nobility in the idea of soulmates, and she lionizes people who buy into the idea.

Beth, in your last response, you offered this arresting passage:

“But why should she when whatever relationship she would have would probably be, at best, a pale imitation of the one she lost? Yes, it’s sad to think of Clare spending so much of her life alone, but it’s also wonderful because Clare had the kind of love that so many people spend their whole lives searching for.”

I must disagree. I appreciate that people find great loves in their lives, but I believe that people can find more than one great love. Furthermore, I roundly disagree with the idea – call it the doctrine of soulmates, if you will – that people only have one great love out there.

![]()

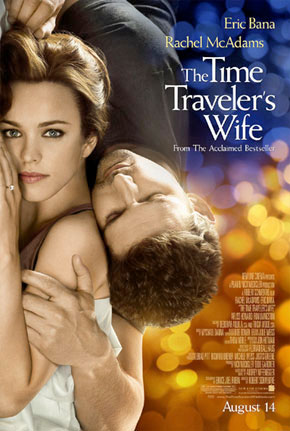

Beth, thanks for agreeing to this spirited discussion. Despite my considerable misgivings about Niffenegger’s perspective and themes, I admire her debut novel a great deal, and I hope we can continue our discussion of this book and its cinematic adaptation with everyone else on the forums.