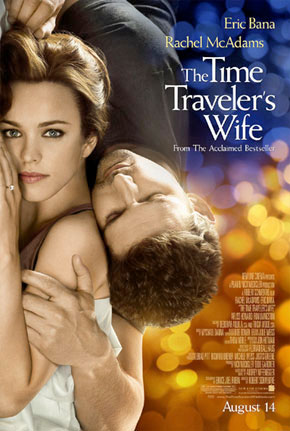

Soulmates and Free Will: A Debate About The Time-Traveler’s Wife

Written by: The CinCitizens

Tony Lazlo responds:

I despise this book’s soul.

Let me explain: Beth, you lay out a load of good reasons to like this book. Just to make it clear where I’m coming from, let me take a moment to heap some praise on Niffenegger’s impressive debut novel.

This book is a tour-de-force in perspective. Both of her leads speak in compelling and believable voices throughout their lives. Niffenegger pulls off the tricky feat of writing from a child’s – and a teenager’s, and a young adult’s – perspective, and she does all this while she keep her book moving along at a brisk pace. This is a short 500-page novel.

She also writes about the vagaries of couples’ and married life very well. Simple moments lingered with me after finishing the book, such as when Henry interrupts Clare’s artistic work, and they have to deal with how an awkward moment broke Clare’s reverie of concentration.

But here’s the thing: You’re right, Beth. This book is about “the idea that true love will survive everything else,” and at the same time, I also submit that it’s about the idea of soulmates. Put simply, I think the idea of soulmates is bullshit, and I think Niffenegger’s presentation of the “love conquers all” theme is repugnant.

Let’s launch into spoilers:

• Henry dies, and Gomez – their long-time friend and Henry’s sometime rival for Clare’s love – makes a go for Clare, but she rejects him.

• Henry gives Clare a letter that reveals that he will see one last time when she’s very, very old.

• An 82-year-old Clare finally sees Henry. She’s alone, and it looks like she never remarried, instead spending her life waiting for that one last time to see him.

Now, this is a tough one. Niffenegger gives us some conflicting evidence. When Henry recounts his meeting with the old Clare in his letter, he says that he trips over “a bunch” of galoshes – surely a sign of a family? (I’ve definitely encountered that argument while discussing this book.

Now, this is a tough one. Niffenegger gives us some conflicting evidence. When Henry recounts his meeting with the old Clare in his letter, he says that he trips over “a bunch” of galoshes – surely a sign of a family? (I’ve definitely encountered that argument while discussing this book.

But here’s the problem: On the book’s final page, in its final passage, Clare says, “Today is not much different from all the other days. I get up at dawn, put on slacks and a sweater, brush my hair, make toast and tea, and sit looking at the lake, wondering if he will come today.” Regarding the idea that Clare may well have remarried: One, I don’t buy it, and two, I think that even if she did, it’s worth noting that she doesn’t mention her family – or any other semblance of a life happily lived – in this key last passage. She also specifically says, “I have no choice.”

I’d also like to point out the disparity in dates between the last two passages. When Henry actually arrives in the future, it’s July 24, 2053. When we see Clare waiting for him, it’s July 14, 2053. It’s only 10 days, but once again, I think the message is clear: Clare waited.

Beth, you called this book “bittersweet.” I think it’s nothing of the sort. I find it morally horrifying. Here’s why: Henry’s letter. Within the context of this fantastical novel, the Henry character had a choice. He could have let Clare live her life, or he could make it so she couldn’t have one. He chose the latter. His letter didn’t include a date, because how could it? Even worse, he fills his letter with a load of gooshy language about how he wants her to move on and live her life. And then he tells her he’ll reappear at some undefined point in the distant future.

Of course I know that Henry and Clare aren’t real people, but Niffenegger is, and by enshrouding her novel in the warm glow of approval for the idea of soulmates – even going so far as to build her central science fiction premise around it – she tacitly approves of Henry’s morally horrifying choice to tell Clare about his distant return, and she approves of Clare’s dead-hearted devotion to him.

It’s an awful message wrapped up in a very beautiful package. Clare should have moved on, and if Henry really loved her, he would have given her the chance to move on. But strong, tough, real-world choices like those had no place in Niffenegger’s pie-in-the-sky narrative.