Sex Week 2012: A Tribute to the Catsuit

Written by: Daron Taylor, Special to CC2K

In honor of Sex Week, I think it’s time to take a look at something so tantalizing, so kinky, something that has become so ubiquitous that maybe it’s flown a little too far under your radar: the catsuit.

In honor of Sex Week, I think it’s time to take a look at something so tantalizing, so kinky, something that has become so ubiquitous that maybe it’s flown a little too far under your radar: the catsuit.

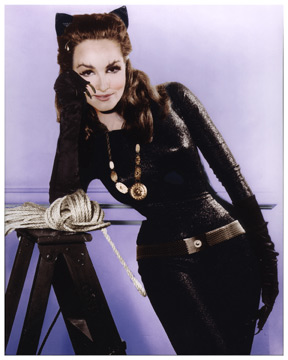

The catsuit went mainstream in film and TV in the 1960s through the characters of Emma Peel and Cathy Gale in The Avengers and, of course, through Julie Newmar and Eartha Kitt as Catwoman. It should be no surprise that when we see a catsuit onscreen, it’s usually on the unearthly toned body of a sci-fi action goddess (remember Carrie Anne Moss in The Matrix, Deanna Troi in TNG or even, with a little twist on the traditional black, Padme’s strategically torn white catsuit in Attack of the Clones?). Perhaps this is because a woman performing stunts outside ‘normal’ women’s roles is seen as deviant, and therefore ripe for sexual experimentation.

Regardless of that connotation, it is obvious what side filmmakers and costume designers have come down on when it comes to what’s aesthetically pleasing versus what’s practical in action wear. Most female superhero costumes in comics are frankly ridiculous, as are many in film (watching Silk Spectre II clomp around and do high kicks in five-inch heels and a garter belt in Watchmen is just painful). The catsuit, then, is somewhat of a happy medium. Tight enough to keep it interesting, while also providing conservative coverage and maybe even an illusion of protection not offered by bare skin while its wearer kicks copious amounts of ass. It is this compromise between female sexuality and physical prowess that makes the catsuit such an interesting symbol of female power in action movies, and mirrors quite accurately the uneasy balance female action stars must strike in their roles. Too often it seems that female action stars are either asked to use their sexuality as a weapon (strangling men between their latex-clad thighs for example) or stripped of their femininity completely.

Film history has seen scores of wonderful, strong, female leads, but unfortunately very few female action stars. Two characters who have been bandied about as examples of hardcore female action leads are Ellen Ripley in the Alien movies and Sarah Conner in the Terminator series. Both seriously hardcore, and both seriously fun to watch. But interestingly in both of these examples, over the course of their respective series we see each woman become leaner and meaner, even while she’s given the role mother and caretaker. Somehow, between the first and second installment of each series, both Ellen and Sarah are given muscles, guns, and children – embracing their femininity, though maybe not their sexuality.

Film history has seen scores of wonderful, strong, female leads, but unfortunately very few female action stars. Two characters who have been bandied about as examples of hardcore female action leads are Ellen Ripley in the Alien movies and Sarah Conner in the Terminator series. Both seriously hardcore, and both seriously fun to watch. But interestingly in both of these examples, over the course of their respective series we see each woman become leaner and meaner, even while she’s given the role mother and caretaker. Somehow, between the first and second installment of each series, both Ellen and Sarah are given muscles, guns, and children – embracing their femininity, though maybe not their sexuality.

Eastern action films have historically been much more accepting of women martial artists as action stars, and in ways that don’t require them to completely abandon their sexuality or femininity. In 1985’s Yes Madam, a mediocre movie with some pretty awesome fight choreography, martial artists Cynthia Rothrock and Michelle Yeoh star as a team of crime-fighting female cops. While Cynthia Rothrock went on to make some truly craptastically bad Western action movies in the 1980s and therefore sadly dismissed as somewhat of a joke, Michelle Yeoh has built up a successful career as a martial artist and actor in Hong Kong cinema – Even starring in the spectacular Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which deals primarily with women fighters and their struggles with their relationships and the limits their femininity has set on them.

The recent film Haywire is a singular example of a woman carrying an action lead in a Western film, in a style similar to say a Jason Bourne movie. It’s actually nicely surprising to see a woman fighter (Gina Carano) star in what is arguably the first MMA action film in the way that a Tony Jaa movie showcases Muay Thai fighting or a Steven Segal movie showcases primarily Aikido. Perhaps in order to completely nullify any kind of fetish attached to the female fighter, the movie makes every effort to distance Mallory Kane (Carano) from her sexuality. Mallory’s ex-lover Kenneth (Ewan MacGregor) puts the movie’s philosophy best when he says: “It would be a mistake to think of her as a woman”. Besides a single extremely chaste scene where she takes her co-worker Aaron (Channing Tatum) to bed in what seems as an effort to demonstrate that yes, she is straight, the film does a remarkable job in keeping the focus completely on Carano’s fighting skill. It is both strange and wonderful to see Carano assume her fighter’s stance, fists raised, bouncing lightly from foot to foot – while wearing a cocktail dress.

The recent film Haywire is a singular example of a woman carrying an action lead in a Western film, in a style similar to say a Jason Bourne movie. It’s actually nicely surprising to see a woman fighter (Gina Carano) star in what is arguably the first MMA action film in the way that a Tony Jaa movie showcases Muay Thai fighting or a Steven Segal movie showcases primarily Aikido. Perhaps in order to completely nullify any kind of fetish attached to the female fighter, the movie makes every effort to distance Mallory Kane (Carano) from her sexuality. Mallory’s ex-lover Kenneth (Ewan MacGregor) puts the movie’s philosophy best when he says: “It would be a mistake to think of her as a woman”. Besides a single extremely chaste scene where she takes her co-worker Aaron (Channing Tatum) to bed in what seems as an effort to demonstrate that yes, she is straight, the film does a remarkable job in keeping the focus completely on Carano’s fighting skill. It is both strange and wonderful to see Carano assume her fighter’s stance, fists raised, bouncing lightly from foot to foot – while wearing a cocktail dress.

But in the end, despite the dispossession of her sexuality, even Carano’s Mallory can’t escape the catsuit. In the film’s final showdown, she runs full speed at her enemy wearing a black, skin-tight outfit plus utility belt similar to costumes we’ve seen on both Catwoman and Black Widow in the upcoming Dark Knight Rises and Avengers movies, respectively. Mallory has in effect become a superhero herself, wreaking havoc and hell bent on vengeance. But rather than see this as a defeated return to silly costume, I choose to see it as that she has proven herself fight after brutal fight and finally donned the mantle of the kickass female.

And so, ladies, it is in this way that I’m proposing that we should embrace the catsuit: Like the superhero’s cape, it is a symbol of power. And more than that – a symbol of our femininity, mixed in with a delicious hint of sexual deviance.