Review: The Hunger Games

Written by: Tony Lazlo, CC2K Staff Writer

It’s not often that all of my predictions for a movie come true, but in the case of Gary Ross’ flavorless, focus-group’ed adaptation of the vastly popular dystopian YA novel The Hunger Games, I was right on almost every count.

It’s not often that all of my predictions for a movie come true, but in the case of Gary Ross’ flavorless, focus-group’ed adaptation of the vastly popular dystopian YA novel The Hunger Games, I was right on almost every count.

To wit:

Jennifer Lawrence, although a skilled actor who turned in a compelling performance as ace archer Katniss Everdeen, was too mainstream and (I’ll soon argue) too white for the role.

The screenwriting team, which includes Ross himself, author Suzanne Collins, and writer Billy Ray, hewed too close to the novel’s structure, resulting in a bloated, unfocused movie that tried to include all of Collins’ characters, no matter how minor.

The production design, although impressive and occasionally very inventive, missed the mark, especially in the Captial, which looked less like the grotesque Botox menagerie that I imagined for Collins’ privileged central city and more like Warren Beatty’s film version of Dick Tracy.

The tone of the movie was all wrong. Gary Ross told the story in grand, heroic style, when the movie needed to be weirder, creepier and far more minor-key in delivery, so to speak.

First, let’s talk about Jennifer Lawrence and my contention that she was too white for Katniss. If memory serves, Collins describes Katniss as having “olive” skin, and while that could indicate any number or combination of ethnic backgrounds — including hispanic, native-american, middle-eastern or black — I relished the thought of a big tentpole Hollywood movie with a well-drawn young female lead who wasn’t white.

Side note: Let me hasten to add that despite my qualms about the choice of her casting, Lawrence herself was great. Her Katniss registered as cunning, caring, brave and strong — everything the role called for. Hell, I had forgotten about how Katniss is raised by a single mom who’s also an absentee parent. Lawrence’s scenes with her (curiously unnamed) mother stood out in a muddled first act, although the casting of a well-known actress like Deadwood’s Paula Malcolmson as the (again) curiously unnamed mother puzzled me.

In fact, let’s talk about the casting, as well as the screenplay. One of my biggest complaints about Collins’ original novel is its narrow focus. Despite being an action novel, a great many of the story’s most gripping arena battles happen offscreen, and we get no sense of the wheeling and dealing that’s happening back in the capital concurrent with the games. Ross and company’s screenplay alleviates some of these issues by intercutting with the tournament’s control room — a wonderfully inventive multi-touch wonderland — as well as with some of Haymitch Abernathy’s deal-brokering back in the capital. Good stuff.

But here’s the problem: Collins over-cast her novel. I don’t understand why the Games have two spokespersons — Caesar Flickerman and Claudius Templesmith — and I don’t understand why Katniss has, for all intents and purposes, two mentors — image consultant Cinna and former tourney winner Haymitch. In a novel, such overcasting is easier to digest, given the medium’s wider scope. The additional characters also contribute to the novel’s underlying satire of a demented celebrity entourage; after all, Katniss’ handlers are essentially preparing meat for a slaughter.

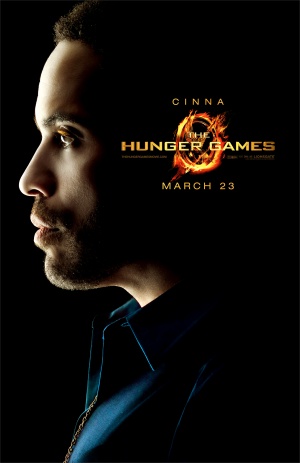

But in a movie, the large supporting cast splintered the narrative’s focus. It’s funny — Haymitch is a fan-favorite, but despite a game performance from Woody Harrelson (channeling Jeffrey Lebowski via Toby Belch), rocker Lenny Kravitz (fashionable and canny as Cinna) registers far more strongly as the movie’s mentor figure, while Harrelson is largely stuck with leaden expository dialogue.

I also want to talk about the production design and the movie’s tone, because they go hand-in-hand. Ross’ movie is far too heroic, mainstream and … well, normal. Collins, to her credit, created a creepy, off-kilter and unusual dystopian world, and it would’ve taken a director with real vision to bring it to life.

After seeing The Hunger Games last night, I drew a comparison between Ross’ Panem and the inert magical world seen in Chris Columbus’ first two Harry Potter movies. We didn’t get to see a compelling vision of the Potter universe until the eminent Alfonso Cuaron reworked the franchise’s tone and imagery in the stellar third volume, Prisoner of Azkaban. In the case of Suzanne Collins’ dystopian world, her story would’ve been better serviced by someone like Cuaron and especially by J.K. Rowling’s first choice to tackle her books: Terry Gilliam.

Jump to timestamp 4:51 to see a far more compelling vision of Collins’ capital and its grotesque citizenry in Gilliam’s masterpiece Brazil:

For the most part, the architecture of the capital looked great – very Albert Speer – and while I admired much of the razzle-dazzle technicolor costume and makeup design, the capital citizens themselves just looked goofy, when they should’ve looked bizarre, alien and demented. To be sure, we got hints of that grotesquerie when Elizabeth Banks’ Effie first came onscreen. Ross canted his camera around Banks’ Victorian-geisha mouth, and I flashed on the “Mouth of Sauron” sequence from Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings cycle:

But then we never saw that kind of minor-key imagery again. Note: I’m using the phrase “minor-key” figuratively. I’m not quite sure how to define minor key, other than to invoke Nightmare on Elm Street. Remember the little girls who skip rope and sing the terrifying “Freddy’s Coming for You” nursery rhyme? They’re singing in minor-key.

Pursuant to that idea: The Hunger Games needed to be bolder, weirder, crunchier. Earlier I praised the inventive imagery in the arena’s control room. I still admire that imagery, but again, we got no sense of tone or perspective. It all looked cool, but then the story’s chief end shouldn’t be to look cool; it should unsettle and unmoor the audience, just like this comparable scene from Peter Weir’s masterful fable The Truman Show:

Can you see what I’m getting at? Gary Ross approached this material straight-on, when he should’ve been standing at a 90-degree angle from all of it.

I’m going to close with a clip from, of all things, The Running Man. Needless to say, Collins’ novel falls into the same literary tradition as Stephen King’s media satire, along with any number of “Most Dangerous Game” bloodbaths like Battle Royale. But in the case of The Running Man, King’s headlong novella made an unusually satisfying jump to the big screen in Paul Michael Glaser’s 1987 Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle.

No one’s ever going to mistake The Running Man for high art, but it is good satire, and despite its simpler moral structure, I’d submit that Glaser’s movie hits many of the notes that Ross’ movie misses. (Please note that I’m only comparing the movies here. I’m a big fan of both original novels, which I think accomplish different ends.) Where Ross’ movie is flavorless, Glaser’s is pungent, funny and uncomfortably kooky. I’ll let this sequence speak for itself: