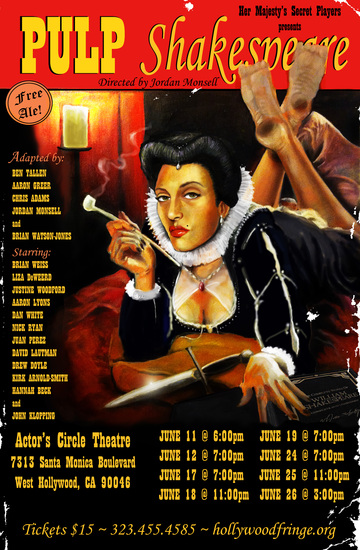

Los Angeles Theater Review: Pulp Shakespeare

Written by: Tony Lazlo, CC2K Staff Writer

Running in Los Angeles, Pulp Shakespeare is an entertaining thought experiment that re-imagines Quentin Tarantino’s instant classic as an Elizabethan play.

Running in Los Angeles, Pulp Shakespeare is an entertaining thought experiment that re-imagines Quentin Tarantino’s instant classic as an Elizabethan play.

Before I go on, please be aware that I’ll be dealing in spoilers. Yes, yes, yes — it might sound silly to warn for spoilers in Pulp Fiction, a story that’s almost 20 years old, but one of the pleasures of this production, by a group called Her Majesty’s Secret Players, is how the play’s five adapters translate the movie’s memorable wordplay and gags into Elizabethan terms.

I call this production a thought experiment because I don’t think it quite works as an actual play — and I don’t think it’s supposed to. It got me thinking about the nature of adaptation, the structure of Shakespeare’s plays, and the love of language that Tarantino and Shakespeare share. (The director, Jordan Monsell, made the same observation in his letter to the audience.)

Any Shakespeare geek has probably seen dozens of modern-dress adaptations of his plays, and one of the fun (and not-so-fun) parts of watching those productions is seeing how the creative team updates certain elements to suit the production’s era.

In Richard Loncraine’s film of Richard III, Ian McKellen’s Richard orders the beheading of Hastings, and in the text, the ghoulish former Duke of Gloucester actually plays with the severed head. Such a choice might seem too lurid for a WW2-era movie, so Loncraine and his team make a clever adjustment to the play’s action. (Skip to timestamp 4:28.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s2uXCaCNAVk

Outside of the Net’s vast stores of steampunk concept art, you seldom see this process happen in reverse, but in Pulp Shakespeare, Butch is recast as a troubled knight, Marcellus a moorish potentate, Pumpkin and Honey Bunny a pair of bandits. Moreover, Lance appears as an apothecary who also sells fine spices and opium, while the movie’s two leads, hitmen Jules and Vincent, appear as courtly assassins. (I’ll talk more about them in a moment.)

Many of Tarantino’s scenes work uncannily well in this setting. It didn’t feel like a stretch to imagine kind-hearted Butch as a down-on-his-luck knight who agrees to throw a jousting tournament for a bag of gold, and neither was it a challenge to imagine Jules and Vincent’s bawdy conversation about foot massages and the “holiest of holies” turning up in Elizabethan times.

But more than that, much of Tarantino’s wordplay and language make delightful transitions to the old era. When Vincent takes Mia out to dinner and asks her about Tony Rocky Horror, Mia’s speech about the nastiness of the rumor mill appears as a rant about listening to the wind. Marcellus’ admonition to Butch to ignore his pride morphs into a condemnation of the deadly sin.

In some cases, no translation was necessary. Jules’ journey from cruelty to repentance would befit any number of Shakespearean heroes, as does his speech to Pumpkin at story’s end.

Speaking of Jules, watching this play made me wonder why Shakespeare never wrote a play with an assassin as the lead character. Dovetailing with that thought is a curious side-effect of this production: In Pulp Shakespeare, the two assassins are essentially members of the court. This isn’t unseen in Shakespeare — James Tyrrell in Richard III becomes one of Richard’s entourage — but the assassins are usually mechanicals, so to speak. (Obviously, characters like Iago are courtly killers in their own right, but I’m trying to think of examples where hitmen by trade assume places in the court.)

In the case of Pulp Fiction’s famous scene where Jules and Vincent slaughter a roomful of college kids, the closest analogue I could think of from Shakespeare also appears in Richard III, when two nameless murderers kill poor Clarence. The slaughter of Macduff’s family in Macbeth also springs to mind. But again, the vibe of Shakespeare’s scenes are different. The murderers are low-class skags, and in Richard III, they appear largely for comic relief. Pulp Shakespeare imagines a play where two characters like James Tyrrell are the leads.

Side note: For me, Pulp Shakespeare was most successful when it really committed to its adaptation and refrained from directly name-checking or sight-checking any of the visual or verbal cues or jokes from the original movie. I don’t mean to sound like a grump saying that, and I don’t mean it as a knock on the play itself because, again, I don’t think the players set out to make a full-fledged play in its own right. Pulp Shakespeare succeeds more as a thought experiment and a rumination on language and adaptation.

That said, the players had a lot of fun with the direct references to Pulp Fiction. Before the story’s first hit, Vincent complains, “We should have broadswords for this.” Jack Rabbit Slim’s — the old Hollywood theme restaurant — turns up as a tavern staffed by people in costume as characters from Shakespeare. It’s all in good fun.

Captain Koons also appears to tell a young Butch about his father’s precious gift, and herein we see one of the play’s most entertaining but least successful moments. The actor playing Koons does a light Christopher Walken impression. Don’t get me wrong; it’s just right, and it’s the only direct impersonation among the cast. (He’s also very funny.)

But again — one impersonation is enough, because the play is far more engaging when it stands on its own feet. Aaron Lyons’ Vincent and Dan White’s Jules both hold up as fresh alternate interpretations of the original characters. (One advantage that theater will always have over film is its capacity to show different takes on the same roles. Lyons’ Vincent is far less spaced-out than John Travolta’s, although poor Vincent’s incontinence is still his undoing. White’s Jules registers as a measure more stately than Samuel L. Jackson’s. You get the feeling that Vincent stepped up in station to become an assassin, while Jules made a step down.)

Before I close, I want to highlight two surprisingly successful scenes:

First: Vincent and Lance’s resuscitation of Mia. I can’t quite imagine it turning up in Shakespeare, but Pulp Shakespeare does such a great job of establishing Lance as a purveyor of unusual remedies and pleasures that I was willing to go along with it when he produces a needle “anointed with strange humors that revitalize the being” (paraphrased). I mean, why not? Shakespeare was enough of a kook to imagine a potion that would make someone appear to be dead for 24 hours, so why couldn’t there be an Elizabethan equivalent of an adrenaline shot? In a similar spirit, Marcellus’ mysterious briefcase makes an appearance as an enchanted treasure chest, and lest that seem too high concept for the time, Shakespeare himself includes a magic treasure chest in Timon of Athens.

Second: Butch and Fabienne’s “waking up together” scene. Such imagery has strong precedent in Shakespeare, but it’s usually in the service of straight-up romance; I’m thinking of Romeo and Juliet or Troilus and Cressida. By recasting Tarantino’s good-hearted, honorable palooka as a knight with an adoring French bride, Pulp Shakespeare delivers a scene that not only feels at home in Shakespeare, but it also just feels real. Kudos to Christian Levatino and Justine Woodford for their performances. (Side note: This scene has always rattled me personally. Butch’s behavior is textbook abusive, but my instinct has always been that he, as a guy with a violent job, had never even raised his voice to his wife until this moment. Still, it’s a powerful scene that works well in any era.)

Last, I want to applaud the play’s recasting of the dastardy sodomite Zed, even though the play’s overall conceit falls apart in the famous “bring out the gimp” scene. I’ll leave Zed’s identity for new audience members to discover in this show, which I highly recommend.

For more information, visit Plays411.