Future Fragments: #yasaves + #yakills, or A Tale of Two Hashtags

Written by: Anastasia Salter, Pop-Culture Editor

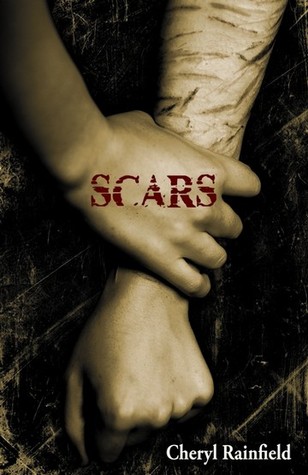

The cover of Cheryl Rainfield’s Scars makes its content very clear. It’s one of many issue novels–books focused on topics of social concern–marketed towards teens. The teenage main character attends therapy and struggles with cutting. The stark imagery is harrowing. So it is perhaps no surprise that this book (and its author) are at the center of a war over children’s literature and the question: how dark is too dark?

The cover of Cheryl Rainfield’s Scars makes its content very clear. It’s one of many issue novels–books focused on topics of social concern–marketed towards teens. The teenage main character attends therapy and struggles with cutting. The stark imagery is harrowing. So it is perhaps no surprise that this book (and its author) are at the center of a war over children’s literature and the question: how dark is too dark?

Every now and then a big media outlet publishes an article where someone sticks their foot in their mouth. This was less of a problem before Twitter. But as the Penny Arcade Dickwolves controversy demonstrated, Meghan Cox Gurdon started the outrage with her article in the Wall Street Journal condemning the rising darkness of Young Adult literature. The resulting outpouring of Twitter rants, blog posts, and even major media rebuttals has brought to life a longstanding war over what culture is “appropriate” for teens.

Debates over children’s literature are nothing new, but they’re usually fought quietly. A local school system pulls books from the shelves after one complaint, or a parent chooses to censor their teen’s reading options, or a book with too “controversial” a topic never makes it out the door to begin with. But this is not how modern warfare over popular culture progresses. The #yasaves hashtag uses Twitter as a public confessional. But responsibility for shaping the confessional rests not with the young adult audience but with the authors, as Cheryl Rainfield’s blog recounts in the origins of the hashtag. But the egalitarian nature of the hashtag structure means that it is reshaped to the needs of everyone who contributes, as even the early history of the hashtag shows.

But this isn’t a fight over content, or at least, not exactly. The proponents of “darkness” in YA simply interpret the value of said darkness differently. Some of the accounts that flooded the twitter-streams were a reminder that the content of the challenged novels often reflects experience, while others noted that these books were the ones that got them through difficult times even if their experiences were not on the scale of the novels themselves.

Often the books were cited as ways to combat isolation–the same effect that the hashtag itself had these last few days. We talk a lot about “getting kids to read,” but we often forget about what motivates reading: the chance to escape. To try a different life. And, perhaps, the chance to connect with others who have the same problem, even if they are the written specters of authors’ memories and understanding of a hazy and constructed adolescence.

The same concerns that motivate articles like the offending WSJ piece motivate suspicion of social media, online communities, and even video gaming. And cutting off these support structures in all their forms is the same as silencing community. A chart tweeted by several in the hashtag dramatizes the battle:

While #yasaves seems political, it is an egalitarian hashtag–the only dominant user is the author who was insulted in the article, and while she accounts for fifteen percent of the tweets, many of those are retweets of others’ remarks within the conversation. Occasionally, the conversation becomes particularly political:

The constant stream of tweets (over 3000 on June 7th alone) highlight the intensity of the feelings these readers and authors have about books. It is an unexpected place for such a conversation to develop–after all, Twitter and other such abbreviated forms of interaction are often equated with the death of in-depth reading–but it is a definite reminder that books remain something worth fighting about. Other ongoing hashtags like FridayReads and one world book clubs provide further evidence that social media and old-fashioned codexes can comfortably co-exist.

But while #yasaves is earnest, #yakills is lovingly satiric. Emerging out of the shadow of #yasaves, the hashtag is a celebration of the shared in-joke. Occasionally, a clueless user asks if this is the opposite of #yasaves. Instead it is, via inclsuive parody, a powerful support. Only rarely does it reference obscure titles.

While the #yasaves hashtag emerged out of defending “dark” YA, the #yakills hashtag is a full celebration of the range of the genre. Jokes reference Harry Potter, Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, Beautiful Creatures, the Uglies series, Hunger Games and many more. The focus is particularly on popular books that are easily recognized, allowing the jokes to travel outside of friendship networks in an ongoing movement that helps draw others into the dueling hashtags. Having the argument over what YA should be reminds us of what it is: an incredibly popular modern genre that attracts some of the best; or a marketing classification that, like a hashtag, helps like-minded texts and readers find one another.