Future Fragments: The Many Familiar Faces of Sherlock Holmes

Written by: Anastasia Salter, Pop-Culture Editor

There’s a very silly fight going on right now that captures many of the big problems with copyright today. BBC has an admittedly fabulous modern-day adaptation of Sherlock Holmes on the air right now, called (ever so originally) Sherlock. Now, CBS is developing a modern-day Sherlock Holmes entitled Elementary. BBC reps have responded to the announcement by noting: “We understand that CBS are doing their own version of an updated Sherlock Holmes. It’s interesting, as they approached us a while back about remaking our show. At the time, they made great assurances about their integrity, so we have to assume that their modernised Sherlock Holmes doesn’t resemble ours in any way, as that would be extremely worrying” (http://screenrant.com/bbc-sherlock-cbs-elementary-lawsuit-aco-148206/). So here’s a question: who gets to say at what point Elementary is too “close” to Sherlock, especially given they both draw on the same source material?

There’s a very silly fight going on right now that captures many of the big problems with copyright today. BBC has an admittedly fabulous modern-day adaptation of Sherlock Holmes on the air right now, called (ever so originally) Sherlock. Now, CBS is developing a modern-day Sherlock Holmes entitled Elementary. BBC reps have responded to the announcement by noting: “We understand that CBS are doing their own version of an updated Sherlock Holmes. It’s interesting, as they approached us a while back about remaking our show. At the time, they made great assurances about their integrity, so we have to assume that their modernised Sherlock Holmes doesn’t resemble ours in any way, as that would be extremely worrying” (http://screenrant.com/bbc-sherlock-cbs-elementary-lawsuit-aco-148206/). So here’s a question: who gets to say at what point Elementary is too “close” to Sherlock, especially given they both draw on the same source material?

Plenty of moments in cinema and TV involve highly similar concepts that arrive very close to one another. My personal favorite was the juxtaposition of A Bug’s Life and Antz in theatres at the same time, with similar struggles and a focus on ants turned heroes making the films a perfect double feature. Sure, there were plenty of differences (Antz was better, and not just because of an ant start that looked impressively like Woody Allen). But the basic narrative and setting was nearly identical. There are many other examples, like the summer of both Deep Impact and Armageddon offering different apocalypse-by-meteor scenarios, or The Illusionist and The Prestige both suddenly thrusting the spotlight on magicians.

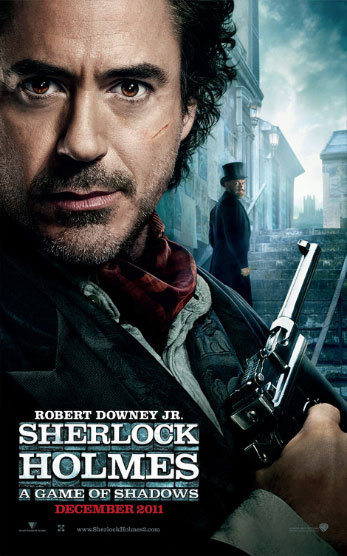

Sherlock Holmes is a hot property: these two adaptations aren’t even the only players, although the Robert Downey Jr. and Jude Law powered movie franchise has come out relatively unscathed because it is far from “modernized” and is competing for space in theatres rather than on TV screens. But the new Sherlock Holmes movie did come out with its own doppelganger, though perhaps not one most theatre-goers would peg, the newest Mission Impossible film.

Sherlock Holmes departs in many ways from the first film, but particularly in realism—some of the steampunk whimsy is lost and replaced with detective tricks including moves straight out of Tom Cruise’s Mission Impossible arsenal (two words: face lift). Perhaps the gadget-highlight of the new Mission Impossible is the use of iPads—as projectors and as hubs for flexible camera extensions for peering around corners. By comparison, Sherlock Holmes has his work cut out for him in the pre-tablet era. But the most direct parallel is in the villains: profiteers and fanatics interested in starting world war.

While both films are unabashedly macho, pulling out tricks, guns and an excessive number of gadgets, the relationship between Holmes and Watson is central to the dynamic. (Arguably, one of many reasons for the popularity of slash fanfiction is the fact the most interesting relationships tend to be between men. In the Sherlock Holmes sequel, the only female worth noting left over from the first installment is unceremoniously removed from consideration quickly.) There’s even a theme of continual suppression of the suggestion of homosexual desire through convenient and socially acceptable marriage—an interesting counterpoint to the career-over-romance mindset espoused in Mission Impossible.

The difference between Mission Impossible and Sherlock Holmes is not unlike the difference between Sherlock Holmes and Sherlock, as David Stringer compared. If Elementary goes forward, no doubt the same judgments will be turned towards it, and whether it is “good” or “bad” it will still be derivative in the same way as every other one of these re-imaginings. It is perfectly absurd to suggest that more players can’t join the mix and create their own “fan fiction” version of these institutions. These characters are being reinvented all the time, whether they take the form of classic investigators or “secret agents”, and the same core draws us over and over again.

This absurd fight over ownership of characters that can no longer be claimed comes right on the heels of a horrifying decision to make it possible to put old works back under copyright—you can read about this shattering of the public domain here. Imagine if Sherlock Holmes were eligible to be placed back under copyright: then these creators could not even compete with one another directly in their visions of the classic but would instead be vying for the permission of the copyright holder. We’d only get to see one of these creators take on the story, and perhaps we’d be cheated out of Jude Law’s perfect Watson or Andrew Scott’s Moriarty? Think how depressing if one of those creators could have kill the others before it began—and yet BBC is already looking to hamstring CBS with veiled threats that will have the legal department on edge, and might well stop the show from ever reaching production. Is this the future of copyright—not a way to encourage creativity, but a way to squelch it in the name of crushing perceived competition?