Future Fragments: The iPad and the eBook

Written by: Anastasia Salter, Pop-Culture Editor

When the iPad launched, many people scoffed that it was just a device for consuming content. It looked a lot like an overpriced toy for reading websites and loading up with eBooks, especially given that one of its “killer apps” at launch was an illustrated color version of Winnie the Pooh. We’re now approaching iPad: the second generation, and Android’s gotten into the tablet game with devices that never seem as sleek as Apple’s ultimate toy. Apple’s native iBooks app has gone from small illustrations of Winnie the Pooh to a full-fledged section of art and picture books as yet another way to thumb their nose at Amazon. The large color screen does offer the potential for endlessly more colorful and dramatic experiences than a Kindle and an iPhone combined, but the best Apple’s own app does is fill that space with static images. If it all comes down to full color pictures, well, there are PDF files that can do that just fine. It’s great that the iPad can take texts so many sources, including the Nook store, the Kindle store, Marvel Comics and many more (well…at least for now).

When the iPad launched, many people scoffed that it was just a device for consuming content. It looked a lot like an overpriced toy for reading websites and loading up with eBooks, especially given that one of its “killer apps” at launch was an illustrated color version of Winnie the Pooh. We’re now approaching iPad: the second generation, and Android’s gotten into the tablet game with devices that never seem as sleek as Apple’s ultimate toy. Apple’s native iBooks app has gone from small illustrations of Winnie the Pooh to a full-fledged section of art and picture books as yet another way to thumb their nose at Amazon. The large color screen does offer the potential for endlessly more colorful and dramatic experiences than a Kindle and an iPhone combined, but the best Apple’s own app does is fill that space with static images. If it all comes down to full color pictures, well, there are PDF files that can do that just fine. It’s great that the iPad can take texts so many sources, including the Nook store, the Kindle store, Marvel Comics and many more (well…at least for now).

But is there really anything novel about the reading experiences on the iPad? Is the future of books in static texts, still arranged in pages, clinging desperately to the paperback shells they weren’t ready to abandon? Is this really the future of reading?

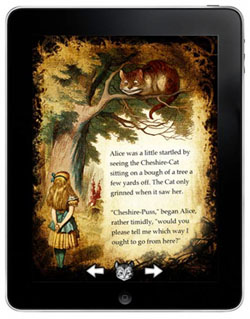

Certainly, the iPad is a content consumption device that begs to be touched: it offers us a glimpse of a world where texts and images are something to be poked out, and they’ll respond in turn. Once I got bored of flipping through Winnie the Pooh and oohing at the full color pictures at launch, I downloaded the first book as app that was supposed to do something better: Alice in Wonderland. Atomic Antelope, a developer that understood that launch buyers would be desperate for novelty, immediately offered a $9 version of Lewis Carroll with playful touches: a pocket watch that tilts with the screen, a falling jar of marmalade, an expanding and retracting Alice and other such simple moving parts that are placed alongside the text. The childlike elements seem to suit the story even as they encourage the reader to skip past the static pages to find more movable goodies.

The Alice in Wonderland app for the iPad excited users with its novelty–so more people tried it.The same strategy has paid off for The Little Mermaid and Other Stories and War of the Worlds—both beautifully created apps with clickable, tiltable, and otherwise active moving parts on top of an otherwise static object. Check out the reading–or play–on War of the Worlds, which even works in some “shooter” moments:

These are the (slightly) more grown-up alternative to the “interactive” picture books that have overrun the app store. Most of these are well-intentioned, if a bit reminiscent of a babysitting app. I wonder if many of them are actually purchased for children: in some of Dr. Suess’s works, including The Lorax and Oh, the Places You’ll Go!, that “read to me” option might be more for decoration as the apps offer a perfect moment of nostalgia. Many of these include reinforcement for language skills–click on an object, hear the name, and the word appears or is highlighted–along with more gimmicky interactions apparently added to keep kids interested. Disney is both the worst offender and the most impressive in this category, with a Toy Story app including animation from the film and games modeled on movie moments. Several of the apps double as coloring books and Disney’s even has a mode where the child can simply brush on the entire screen spot by spot and the “right” colors will gradually reappear. A valuable addition to the reading experience? Probably not, but it’s a solution to a bored kid in the back seat more than a literary vehicle.

Other apps for a slightly older audience offer little more in the way of literary value. The Choice of the Dragon iPad app, one of several by Choice of Games, is like a Choose Your Own Adventure novel and similarly sparse on style. It does embed a role-playing element: your choices “shape” your dragon’s stats, or strengths, and limit your options as you progress. As moral spectrum games go, it’s no Knights of the Old Republic, and as stories go, it’s no Dragonlance, but it’s about on par with the many quick release CYOA “gamebooks” of the 80s and 90s. (They weren’t the future of literature then either.)

On the more narrative side of things, Cathy’s Book is a port of an already hugely popular young adult novel with ARG elements—physical objects, URLs and phone numbers link the text out into reality. Sadly, it’s only available sized for iPhone right now, which is a shame. It remains one of the most innovative and engaging examples of using embedded objects to add to the story’s meaning rather than as just another flashy gimmick. Victor and Cathy’s story includes Cathy’s drawings and animations, embedded wiki articles, and other pieces of evidence to engage the reader in Cathy’s mystery.

The multifaceted text feels like how Danielewski’s House of Leaves might translate to iPad form: another way to get at all the interlinked texts and include layers and layers of linked materials radiating out from the main story as entryway into another reality. It’s a start towards realizing the strengths of an iPad as reader as a web-connected device that also isn’t reliant on linear order. Just because something would be “out of order” in a book doesn’t mean it has to have any bearing on a digital text–the pages are all in our heads.

Cathy’s Book may link to the outside world, but it’s a complete text in itself–there’s no room for growth, even though there’s still a whole community dedicated to figuring out the story. As I mentioned in my top 10 of 2010, Neal Stephenson and Greg Bear’s Mongoliad is a collaborator writing project that allows for fan participation–so it’s a text that continually expands beyond what even the great writers at its head have considered. As it is now, it’s a strange and difficult to navigate space with a narrative on to of what is essentially a wiki. There are many pages, but the structure is still evolving.

Strange Rain, on the other hand, has abandoned pages altogether. One of the most recent and experimental apps in the iPad collection, it iis basically a kinetic rain simulator with an embedded narrative. The app encourages you to indulge in holding it over your head and watching the rain “fall” on you, and the rain itself is responsive to your actions. But in story mode, the app acts just as responsive to gesture, and your motion conveys your interest in pursuing the character’s line of thought. In that sense, it’s the most adaptive text yet on the iPad: what you move and touch actually changes what you see instead of just triggering a quick reaction. It’s hard to imagine the model being successful for a full novel, as it doesn’t allow for the processing of much text in one sitting, but for text as experience–where the point of entry is less important than the feeling of being in the middle of it–it’s the most future-forward app to date. (Of course, it’s worth noting that in many ways it owes a great debt to the electronic literature that’s been going on since well before iPads.)

So what’s the line between these stories and the graphic adventure games being ported onto the iPad? Classics like Monkey Island, Seventh Guest and Flight of the Amazon Queen, Simon the Sorceror are heavy on narrative, with puzzles standing between the player and the next pivotal scene. New titles like Stroke of Midnight, Salem Witch Trials and series, Drawn, and the new Sam and Max are also part of the growing adventure game collection and the continued popularity of these titles suggests that interactive narrative (now of the touchable variety) has a strong following.

Wherever the murky line between these games and the interactive books is placed, Frotz is somewhere straddling comfortably. Frotz isn’t so much something new as it is a tool for getting at lots of content from the interactive fiction world. It provides an emulator for playing text-based games for those few who both enjoy highly puzzle-focused text games and are willing to struggle through typing verbs on an iPad keyboard. And given Andrew Plotkin, a legendary creator within the IF world, just had a KickStarter project funded through the roof to create interactive fiction for the iPhone, Frotz is just the beginning.

And perhaps that’s the most hopeful thing that can be said of all these projects: these are just the beginning. They aren’t yet the future of literature, although they point at ways nonlinear forms can tell complex stories and environment and narrative can coexist in a way that gives us something better. Most of it is gimmicky now, in a way that will quickly wear thin–no matter how much fun it is to poke the invaders in War of the Worlds and see them use their lasers to fry the tiny humans. Perhaps the next stages will reach beyond gimmicks and give us new types of stories to poke and prod.