Future Fragments: The Hobbit and the Problem of the Hyperreal

Written by: Anastasia Salter, Pop-Culture Editor

Like many fantasy geeks, I grew up on The Hobbit. I remember a sprawling map of Middle Earth drawn by my father and nights spent listening to tales of Bilbo Baggins before I started reading them for myself. Thus I followed the ups and downs of the making of the film version with keen interest, mourning the loss of del Toro from the director’s seat and examining the trailers for signs of the same loving translation that made Lord of the Rings a surprising success. So now that Jackson’s first installment of the epic retelling of The Hobbit has hit theatres, how does it stand alongside the original text? And what does all this new technology and added “framerate” really mean for the future of cinema?

Like many fantasy geeks, I grew up on The Hobbit. I remember a sprawling map of Middle Earth drawn by my father and nights spent listening to tales of Bilbo Baggins before I started reading them for myself. Thus I followed the ups and downs of the making of the film version with keen interest, mourning the loss of del Toro from the director’s seat and examining the trailers for signs of the same loving translation that made Lord of the Rings a surprising success. So now that Jackson’s first installment of the epic retelling of The Hobbit has hit theatres, how does it stand alongside the original text? And what does all this new technology and added “framerate” really mean for the future of cinema?

It is impossible to approach the adaptation of a beloved book without prejudice. I am very grateful that growing up I never saw The Wizard of Oz, as my parents had gotten me all of L. Frank Baum’s books and studiously avoided the movie version. When I did finally see it, 20 years after first reading the stories, I was appalled. The cartoony witch, the “ruby” slippers, the omission of the glasses providing the Emerald City’s parlor trick, the implication that the entire journey was just a dream–I rejected all of these as unworthy of Baum’s work, and I’ve never watched the film again. Even more modern classics often arrive in theatres accompanied by discussions of changes, from the alien-free ending of Watchmen to the sidestepping of Dumbledore’s funeral in Harry Potter. So it is no small feat for Jackson’s The Hobbit to be watchable, and certainly faithful to a fault, good news given this is a story that most of us watching know so very well.

New Zealand’s tourism industry has decidedly profited from being the set of Middle Earth, and thus we’ve come to expect impressive landscapes at every turn in Jackson’s adaptations. But The Hobbit’s most disconcerting characteristic stems from that very realism and a dissonance between imagery and story that arises again and again throughout the film. It may sound odd to accuse a fantasy movie of poor fidelity to realism: but ultimately, all fantasy worlds fall somewhere in a spectrum of realism that is not interrupted by the presence of goblins or dragons. We can accept that dragons are simply par for the course in a world, but if we are to believe that the stakes of dragon-slaying are high than we must similarly believe in the rest of the peril. The Hobbit as a film could not decide what was at stake or whether its bumbling questing dwarves and hobbit were cartoon characters or forebearers of the fellowship of the ring.

This dissonance was heightened by the technology that comes bundled with it. If you’ve scanned through local listings to pick your showing of The Hobbit, as I did, you’ve already no doubt encountered the back and forth over high-framerate showings. While 3D is apparently inescapable in most major releases today, HFR showings add yet another layer of technical mystique, promising an image fidelity beyond what any home theatre can achieve. It is precisely the sort of fidelity that I can imagine at home on the giant projection screens of Disney rides, accompanied by swaying seats and the invitation to feel transported to another realm. But for showing fantasy, I found it entirely alienating–a constant reminder that what I was watching was not Middle Earth, but New Zealand, delivered in hyperreal detail but ultimately depressingly worldly.

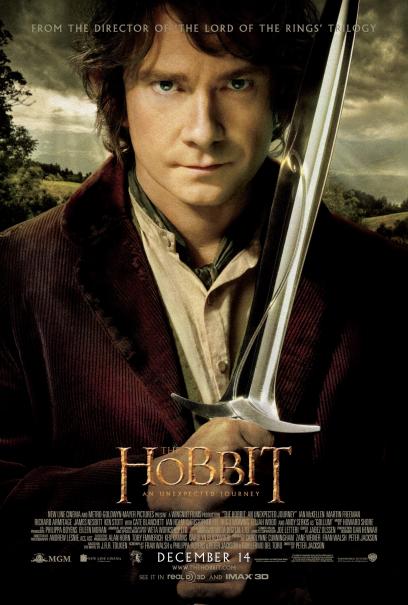

What is it that I found so offputting about the hyperreal? Perhaps it is in part that this framerate offers a fidelity under which artifice shrivels, as in disconcertingly smooth shots of bald head-caps or too-revealing close-ups of neatly manufactured hairpiece lines. But there’s also something too bright and glossy about this high framerate Middle Earth, as if a certain amount of dust and grime has been wiped away and with it the feeling of real conflict and stakes. Scott McCloud pointed out in Understanding Comics that a certain level of abstraction invites us to identify with and project upon a character, and that comics rely upon iconography precisely for that effectiveness. The hyperreal, too-clear image of Martin Freeman as Bilbo Baggins mostly reminded me that he is also Sherlock’s Watson, not to mention his comic turn in Love, Actually. Combining that with 3D made me constantly aware I was watching a film, so that the artifice was more distracting than immersive–the HFR and 3D don’t comfortably fade away but instead put themselves in front of the film, making it hard to know where to focus.

Will the future of cinema be this crystal-clear, high resolution mystique? Based on all the grumbling HFR showings have caused, I’d like to say not–but then, there’s been plenty of grumbling about 3D and we’re still subjected to seemingly endless sequences of dwarves tumbling down a 3D mountain. Perhaps there will be a work that will show HFR’s true potential, but I’d speculate that it won’t be a work of fantasy but a story designed for the hyperreal, with a landscape and story more clearly bound.