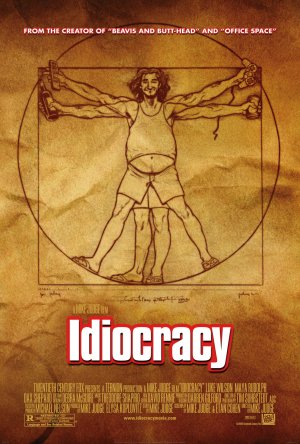

Future Fragments: Revisiting Idiocracy

Written by: Anastasia Salter, Pop-Culture Editor

Every now and then I re-watch Idiocracy, a movie that came out in 2006 and predicted the coming apocalypse of the intellectual elite. In a disturbingly insightful ten minute opening sequence, a pseudo-documentary style accompanies interviews with two couples. One, the intellectual pair, is putting off the decision to have a child, concerned by financial ramifications, repercussions on their careers, and a multitude of other obstacles. The second pair, on the other hand, is completely unconcerned with their situations and reproducing continuously both in and out of marriage. The movie’s premise? As “smart” people opt out of reproduction, and “ignorant” people reproduce at stunning rates, the world is getting progressively stupider. We should now be five years into the cycle, or 1/100th of the way to the point of no return the movie conceived—so did they have a point?

Every now and then I re-watch Idiocracy, a movie that came out in 2006 and predicted the coming apocalypse of the intellectual elite. In a disturbingly insightful ten minute opening sequence, a pseudo-documentary style accompanies interviews with two couples. One, the intellectual pair, is putting off the decision to have a child, concerned by financial ramifications, repercussions on their careers, and a multitude of other obstacles. The second pair, on the other hand, is completely unconcerned with their situations and reproducing continuously both in and out of marriage. The movie’s premise? As “smart” people opt out of reproduction, and “ignorant” people reproduce at stunning rates, the world is getting progressively stupider. We should now be five years into the cycle, or 1/100th of the way to the point of no return the movie conceived—so did they have a point?

The story of Idiocracy follows two perfectly average people (for our time) who are accidentally left in a suspended state until the capsule reopens five hundred years later. At this point, society has completely degraded, victims of blind consumerism who use a sports drink to “water” the plants and are thus in the process of completely destroying their ecology. The average folks, now the smartest people on the planet, are left to “save the world.” Companies have gone the way of the net revolution and specialized in what they know sells: cheap food and sex, often at the same time, as this article documents.

Here’s the trailer to give you a taste—or refresh your memory:

Once you’ve watched the trailer, it’s worth checking out the YouTube comments–there are a number of people who enjoy pointing out how on-target this film seems to them. One wrote: “This isn’t science fiction. This is science FACT.” There’s also a blog post with an impressive list of “Modern Signs That Idiocracy is Becoming a Reality.”

Entertaining though this narrative is, and as much as the Jackass franchise and stunt YouTube videos might seem akin to the “Oww My Balls” TV show that is a hit in the idiot-dominated future, Idiocracy forgets the role of interactive media in the future entirely. Everything in this imagined future is passive—and certainly, part of this reflects the increasing automation that we are seeing, as users of technologies increasingly don’t even have to know how something works to make it function. Some of these technologies are clear heirs to the same impulse that created the iPad, and on the surface the iPad can appear to enhance these problems. Apps are programs that have been ultra-simplified for the user to demand no fuss or knowledge to install—they take control of the environment and eliminate much of the user work.

I recently bought a smartphone, and as I kept it at my side while rewatching the film it occurred to me that this film still imagines a future with phonebooths. These spots are particularly jarring when you consider that phonebooths are nearly impossible to find today, as a recent Wonderella comic highlighted beautifully. As I looked closer, it wasn’t just the smartphones, but the laptops, the computers—anything that showed technology as connecting or allowing for creativity was cut from this version of the future.

The very term smartphone carries with it a note of foreboding—if the device is intelligent, what does that make the user? Perhaps that’s part of why I personally held off so long. The convenience a smartphone offers can be an excuse for laziness of all kinds: I no longer have to track my task list and calendar with the same mental attentiveness, because I know my devices will sync it for me. I can recall a piece of information instantly with 4G search, which means I’ll spend less time in a conversation delving into my own knowledge to pull out the name of an author or a half-remembered film.

And, of course, with the help of 4G, I’ll never be really alone as long as the battery is charged. Being alone with one’s thoughts can be underappreciated: in the future imagined by Idiocracy, the blaring screens with their competing messages simultaneously pressing on the attention ensure that thought is unlikely. The film imagines that eventually we’ll be unable to resist, not unlike the passengers of the ship in Wall-e who can’t see anything of their environment but the screens in front of them as they float through the deck in their powered chairs.

A smartphone is an active device: those college kids filming themselves doing crazy YouTube stunts? Maybe the stunts aren’t the greatest of ideas, but they’re broadcasting. They’re doing something, creating something, sharing something. Idiocracy imagined that we could be content to go back to being completely passive—that watching fart jokes and violent humiliating executions will one day be enough to sate the collective cultural appetite. And it’s true, there’s an app for that. But Apple didn’t make it—creative if bored individuals made the fart apps and their many variants.

Idiocracy wasn’t just imagining the death of intellect but the death of creativity. There are plenty of reasons for concern, including, of course, the tendency of Hollywood to release nothing but remakes, sequels and other bland fare right now and the equal tendency of the public to consume it willingly if not cheerfully. The movie deserves its place as a warning, if exaggerated, of the slippery slope of public attention.

But as long as a few kids can create a film, Kevin Smith style, and release it on the web? Or to the iPad? Culture will probably be fine, apocalypses aside. The world of Idiocracy’s film couldn’t accommodate devices of action because they’d screw up the storyline—collective freedom of creativity is the best possible antidote to their vision.