Future Fragments: Katniss, Bella + “Girl Power”

Written by: Anastasia Salter, Pop-Culture Editor

The hype leading up to the release of The Hunger Games film has finally come to an end, as both fans and the uninitiated flocked to the theatres last weekend to seal the sensation with record box-office numbers. And now, those who haven’t paid the book series (and its role in bringing the apocalypse + dystopia genre to the forefront of YA) much mind are looking for explanations–why is Hunger Games so popular? But the answers they are finding, particularly in comparing Hunger Games to another hugely popular YA franchise, Twilight, are not necessarily so great–and the “girl power” represented by the film is not without complexity.

The hype leading up to the release of The Hunger Games film has finally come to an end, as both fans and the uninitiated flocked to the theatres last weekend to seal the sensation with record box-office numbers. And now, those who haven’t paid the book series (and its role in bringing the apocalypse + dystopia genre to the forefront of YA) much mind are looking for explanations–why is Hunger Games so popular? But the answers they are finding, particularly in comparing Hunger Games to another hugely popular YA franchise, Twilight, are not necessarily so great–and the “girl power” represented by the film is not without complexity.

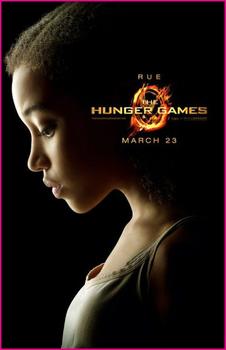

Tony has already reviewed Hunger Games and hit on many of the same complaints I have, so I won’t reiterate them—needless to say, I agree Terry Gilliam would have done a much better job, and this world needed to be cast through a darker and more satirical lens. But these complaints are not the type attracting most attention right now. Some of the outrage that has surrounded the film is downright appalling: as a recent Jezebel article highlighted, a number of “fans” were appalled to discover that the book’s symbol of innocent death, Rue, was a black girl rather than the blonde white girl many of them had imagined (despite clear descriptions in the novel to the contrary—a reminder of the ability of readers to skim over what they do not wish to read.)

These types of rumblings are a strange counterpoint to the usual Hollywood trend–remember the incredible whitewashing of Avatar: The Last Airbender?–but that doesn’t mean there wasn’t a little whitewashing in Hunger Games too. The story belongs to blonde-before-the-dye-job Katniss herself, who does offer a more aggressive and self-sufficient heroine than our usual fare but who suffers some in the conversion to film. In the novel, Katniss’s inner monologue reveals much of her calculation, allowing for an understanding of her actions as motivated by the desire to survive–not by the love triangle the movie seems to highlight. Katniss loses some of her edge in translation, even before the film’s assocation with “girl power” began. This connection was helped along by pieces such as the Salon article by Laura Miller suggesting that the box-office success of The Hunger Games is a testament to “girl power”: a term more readily associated with the era of the Spice Girls than the current audience for YA. Such hype does the same repackaging of the film that Katniss’s stylists use to turn her into an “object of desire” to sell to the Captiol’s sponsors: it’s a convenient sales pitch, but not a real identity.

“Girl power” and the deragotary term “chick flick” are terms not usually connected to critically acclaimed films. There are plenty of movies that are considered to be for a female audience that get saddled with these associations, and it’s not always meant kindly. Check out the demographics on Sister Act, Clueless, Miss Congeniality, and their many brethren—when men are in the audience, it’s stereotypical to assume they are on a date. The Twilight franchise doesn’t inspire the same sort of critical praise as Hunger Games: in fact, Twilight fans remain one of the more mocked fandoms, called “Twi-hards” and dismissed for their affection for Edward and Jacob. The Twilight franchise might cater to female desire, but it’s success doesn’t come with respect.

If there is something of “girl power” to be remarked upon on Hunger Games, I cannot help but cynically see it in a different light–this is a story written by a woman, with a female heroine and, yes, even a love triangle, that still appeals to men. The audience was reported as 39% male–hardly the same demographics as Twilight’s 20% male viewers (as reported in Salon). Harry Potter, Twilight, and Hunger Games were all written by women, but Harry Potter pushed Hermione to the role of sidekick. That fandom is just as powered by women fans, just as every fandom from Star Trek on has had its hordes of female fanfiction writers, arists, and devotees, but its male lead pushes it into acknowledged unisex territory. Would we even be discussing girl power if the movie had instead focused the camera on Peeta and his quest to protect the girl he loved in an arena of death?

Perhaps the most interesting problems await the franchise as it continues. Presumably, the trilogy will be adapted, and both the violence and the rebellion ramp up with each installment. Just as the Twilight series has transformed with each film thanks to increased darkness (and some decidedly gruesome elements far removed from the early high school love affair), the Hunger Games trilogy sees Katniss grow from “girl” to decidedly grown-up. With any luck, by then we’ll be throwing out terms like girl power (and its whitewashed, sterilized associations) and instead praising a hero at the center of a powerfully subversive tale.