Future Fragments: Fantastic Flying (e)Books

Written by: Anastasia Salter, Pop-Culture Editor

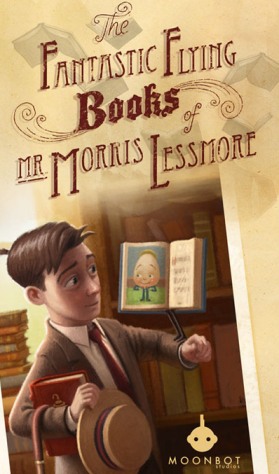

The magic of books has long been explored in stories out of the physical page: books are portals, gateways, links between worlds and holders of endless knowledge. Whenever popular wisdom says that reading is on the decline, fears of the loss of reading’s magic move to the forefront of debates over a linked descent in imagination and education. So even as more technologies have stepped into these roles, the book itself has remained a cultural fetish object, its power explored in film, television, and now on the iPad in the new app “The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore.”

The magic of books has long been explored in stories out of the physical page: books are portals, gateways, links between worlds and holders of endless knowledge. Whenever popular wisdom says that reading is on the decline, fears of the loss of reading’s magic move to the forefront of debates over a linked descent in imagination and education. So even as more technologies have stepped into these roles, the book itself has remained a cultural fetish object, its power explored in film, television, and now on the iPad in the new app “The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore.”

I’ve written before on the gradual rise of dedicated book experiments on the iPad: the Alice in Wonderland app that first made a splash at the iPad’s launch led to imitators caught in similar gimmicks. For instance, a War of the Worlds app allowed for shooting at humans with the touch of a finger offers the type of technical magic that a physical book does not contain. At the same time, obscuring pages of text in favor of flashy animation distracts from the story. These books become about the experience–not whatever it was that was magic about books to begin with.

Originally a stunningly beautiful short film, “The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore” is now perhaps the most gorgeous app to be released to the iPad to date. The story is a fairy tale of a man who lives his life by the book and finds himself the caretaker of a room filled with magical books, each desperate to share its story with him. In this world, the love affair with books goes both ways–the books return their readers’ love.

The style of the film, rather like its content, is perched between worlds of tradition and modern aesthetic technique. The iPad adaptation similarly straddles worlds, using the film’s haunting images as illustrations to the story that come to life at a touch but still “flip” like the pages of a picture book. Sections of the pages hold hidden interactivity, like the letters of an alphabet cereal waiting to be rearranged or the notes of a piano.

Is there anything gained in this hybridity?

Well, unlike a typical transmedia storytelling approach, the app and film are here redundant: the added aspects of the iPad app aren’t about narrative, but about play. Perhaps the most powerful role of the app is to bring a genre that is usually ignored to the attention of more viewers. Short films are the category at the Oscars mostly unknown to those not lucky (or interested) enough to attend film festivals, and given that even the best short films receive much less exposure. Normal theater distribution has no system for these films. The iPad has the potential to bring them to the nonspecialist, and the change in format that Moonbot has experimented with makes them more than yet another thing to watch passively through iTunes or Netflix.

Perhaps most importantly, the new format increases the cross-generational appeal that was already inherent in the content. It falls into the same category as apps by publishers like Disney, who brought many of their franchises into the app store by repackaging pieces of films into picture books not unlike this new effort in form, though less elegant in their implementation. Children’s books like these are some of the bestselling apps on the iPad, even though the form factor and price tag might suggest otherwise. But it seems though the iPad may be priced for adults, but as the recent marketing campaign highlights, it’s children that see the iPad as “magic.”

Note the image that accompanies the announcer’s proclamation of the iPad’s magic: the Alice in Wonderland app’s tea party scene looks out after a montage of productive app screenshots. The book is once again at the forefront, but the peddlers of technology suggest that the wonder is in the technology, not in the timeless story. And perhaps such observations are to be congratulated–anything that gets a novel at the center of a screen is a good thing, right?

After all–books are not the center of our popular culture. Jasper Fforde’s Thursday Next series imagined an alternate world where literary texts would be as popular as, say, reality TV–a world where all media would be literature-centered and there would be so many people changing their names to their favorite literary characters’ or authors’ name that they would need numbers to keep them all straight. Midnight showings of Shakespeare with enthusiasm to rival a midnight showing of Rocky Horror Picture Show: not quite the world we live in. But with bestsellers like Twilight, Harry Potter and many others filling our theaters, perhaps we aren’t looking at such a bad time for the book after all.

It is perhaps most natural for books to explore the nature of this enduring appeal, rather than other media, and certainly many have. Keith Miller’s mostly overlooked fairy tale quest novel The Book of Flying offered a world where books held the key to self-transformation and marked the difference between life on the ground and a more privileged life in the skies above. Inkheart was an odd choice for a film adaptation: the book celebrates the very act of reading aloud as a way to transport characters in for another realm, a power that is somewhat out of place when translated to movies.

Perhaps in the end these debates over the fusion of books and interactivity are a reminder of how much we still value the books themselves. More of the physicality of the text is mimicked than is ignored, from the illustrations that fill the pages of the iBooks version of Winnie the Pooh to the page swipe action that has become ubiquitous–they even interrupt the motion of “The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore.” The magic isn’t confined to any one medium.