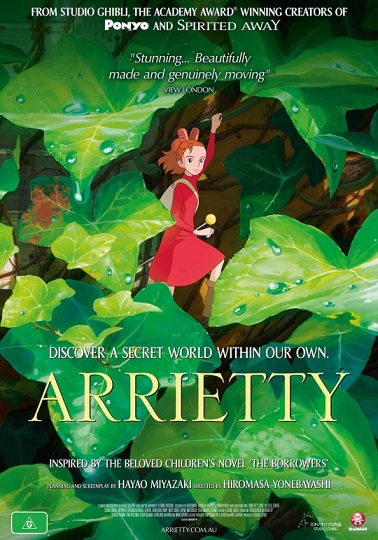

Future Fragments: Faith and The Secret of Arietty

Written by: Anastasia Salter, Pop-Culture Editor

Animation allows us to tackle subjects that would be too uncomfortable in a more realistic medium, as everything seen through the lens of “toon” is slightly askew, giving us a chance to laugh at ourselves even as we are forced to consider the mirror staring back at us. Studio Ghibli films are some of my favorite cinematic experiences, and hold particularly close to that goal of animation. I have a giant poster of Totoro—my personal hero—in my office. So when a new one shows up in theatres, I’m there as soon as possible. When ads started running telling us that we were finally going to get The Secret of Arietty in the US, I couldn’t wait to see what they were commenting on this time. However, even knowing the ‘original’ source text, The Borrowers, wouldn’t necessarily reveal the discourse on modern faith woven throughout the film–a film that itself stands as proof of animation’s continued power.

Animation allows us to tackle subjects that would be too uncomfortable in a more realistic medium, as everything seen through the lens of “toon” is slightly askew, giving us a chance to laugh at ourselves even as we are forced to consider the mirror staring back at us. Studio Ghibli films are some of my favorite cinematic experiences, and hold particularly close to that goal of animation. I have a giant poster of Totoro—my personal hero—in my office. So when a new one shows up in theatres, I’m there as soon as possible. When ads started running telling us that we were finally going to get The Secret of Arietty in the US, I couldn’t wait to see what they were commenting on this time. However, even knowing the ‘original’ source text, The Borrowers, wouldn’t necessarily reveal the discourse on modern faith woven throughout the film–a film that itself stands as proof of animation’s continued power.

Hollywood’s been taking a lot of heat lately for children’s movies with “agendas”, like the watered-down environmentalism of the new Lorax film and the pseudo anti-capitalist Muppets. Yet most of these are diluted to the point of being nearly unrecognizable, with even harrowing moments like the mountains of trash in Wall E eventually left behind for a more fast-paces action humor film. Certainly, each has its message, and often one not just for the children in the audience. Remember the opening of Up? That’s just one example of a moment that only gets more powerful with the viewer’s age.

Studio Ghibli films, on the other hand, are never watered-down–despite their distribution through Disney in the US. Their environmental themes (think Princess Mononoke) are at the center of endless struggle, the magical and the natural is always threatened by the industrial, and the child is often the only one who can perceive the threatened world. Just as in Kurosawa’s dreams, a young boy weeps for the cherry blossom trees his family cut down, and the spirits give him one last glimpse of what has been lost, Studio Ghibli films invite us to see our own world differently. This quiet confrontation with the reality of human nature puts The Secret of Arietty much higher on the list of films with “agendas” than the Lorax’s new car salesman presence.

The villain in Arietty disturbed me more than most Disney villains, and stands out even for Ghibli for her twisted motivations. She’s a woman out to capture The Borrowers, reminiscent of the shadowy agents who came for E.T. But her real power comes when you try to put yourself in her shoes: she’s seen the evidence and heard the family’s stories about the little people to the point where she believes, even if the outside world thinks she’s crazy. But none of the little people ever reached out to her. Imagine living for years absolutely convinced that UFOs exist. Now you find out that not only are they real, but the aliens have been dropping in to have tea with your next door neighbor at Area 51. Your neighbor gets all the validation of their own belief, and you get glimpses that make you sound crazier than ever.

If there’s a moral to Arietty, it’s the danger of a belief that means more than the thing you believe in. The film succeeds as a critique of the need for validation, suggesting that belief or disbelief of any type works better as a private affair. The empty dollhouse with the perfect world created for the Borrowers can never be their home, not as long as a nagging need for answers would risk their appearance on a dissection table. Another constant aspect of Ghibli productions is the range of roles for women. Arietty is coming of age, ready to start brrowing on her own, and that tension plays out as part of a bittersweet ending to a beautiful film. Arietty would never be a kept “little person” in a doll house, no matter how beautiful it might be.

There’s also a critique of class relations throughout the Secret of Arietty. As the story juxtaposes the fate of a sick boy from a wealthy family, and a girl from a family that relies on stealing that which won’t be missed from the larger world. Heavy-handed generosity from the boy, from the same misguided instincts that caused his mother to try and make a house and invite the Borrowers to live as privileged dolls, almost destroys Arittey’s world. The parallels of The Borrowers with a colonized people, looking to make pieces of the invader’s world into their new strategy for survival, goes disturbingly hand-in-hand with the woman’s desire to see the “little people” captured and revealed.

While US animation gets to some amazing places, this type of gentle story with its clear connection to human nature in the face of the unknown is not our usual fare. It is a reminder of the new places adaptations can go: a british children’s book re-imagined by a Japanes studio and finally distributed for an American audience. The future of cinema should reflect a more inherently international landscape. With digital distribution, there’s no reason for fims to be held in their country of origin before they are released in the US and around the world. These stories offer a chance for necessary cultural reflection, one that is particularly timely given the debates founded on belief in the news every day.