Future Fragments: Child of Eden and the Kinect’s Rebirth

Written by: Anastasia Salter, Pop-Culture Editor

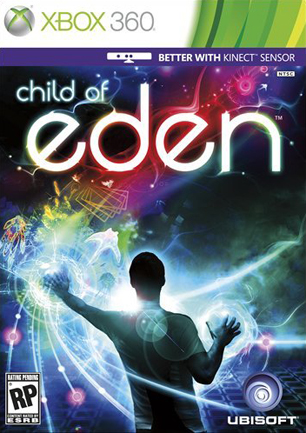

Once the novelty of the Kinect’s motion interface wore off, I was left alongside many early-adopters waiting for the second act. And it was a long wait–despite a few E3 demos promising unique gameplay in the future, most of the games from the Kinect’s first year were variations on the same. Physical activity, measurements of form or rhythm, mini-games with next to no semblance of narrative and progression that only comes through increased difficulty. But last week, Child of Eden finally launched, and while it is available for a number of platforms it is particularly significant for the Kinect. It’s the first of hopefully many games to address the challenge of creating meaningful play with novel interface design, and it begins to answer the question: can the Kinect transcend the casual game stigma?

Once the novelty of the Kinect’s motion interface wore off, I was left alongside many early-adopters waiting for the second act. And it was a long wait–despite a few E3 demos promising unique gameplay in the future, most of the games from the Kinect’s first year were variations on the same. Physical activity, measurements of form or rhythm, mini-games with next to no semblance of narrative and progression that only comes through increased difficulty. But last week, Child of Eden finally launched, and while it is available for a number of platforms it is particularly significant for the Kinect. It’s the first of hopefully many games to address the challenge of creating meaningful play with novel interface design, and it begins to answer the question: can the Kinect transcend the casual game stigma?

Child of Eden starts to address that challenge by redefining it: can the Kinect create a feeling of story? The game begin as an unusual creation, as the design document itself was a forty-page poem. Those poetics inform every aspect of the game’s design, from the connection of sound effects to the motion of the player’s hands and the struggle to transform a corrupt space back into a beautiful one. The game’s action can feel absolutely frantic, but it isn’t the chaos of a first-person shooter. Instead, it feels like conducting a symphony, and echoes of Mickey Mouse’s wand waving in Fantasia emerge in the ability to create and destroy with controlled hand-waving. The interactions do involve weapons and “guns,” but the use of them is so abstract that the metaphor of the shooter seems oddly out of place. The feeling is different enough that the play at moments feels truly new.

The game is infused with a serious dose of cyberpunk, as the opening narrative explains that Eden–the “garden” the player is charged with recovering from corruption–is in fact the next stage of the Internet. The player’s motion through hectic levels is thus motivated by the desire to free a beautiful woman–the first born in space, now reborn in cyberspace–from an Eden that has turned on her. The viruses the player battles are out to destroy Eden’s memories, a linkage that ties the highly abstract world of play with the slightly more grounded narrative that exists between levels.

Visually the game world is reminiscent of images of cyberspace from movies like Johnny Mnemonic, which imagined a constructed virtual realm of knowledge that could be manipulated through physical gestures–not unlike the interactions the Kinect itself makes possible. And of course, with the Kinect SDK now open for creative concepts, interfaces like this are already on their way for a lot more than play:

This abstract view of the connection between physical action and the resultant motion in game is far less literal than many of the games demonstrated at this year’s E3, but the importance of narrative is being upheld in several of the most anticipated titles. For instance, the long-awaited Kinect-enabled Star Wars game offers lightsaber-swinging gameplay but promises to incorporate that combat into a more dramatic narrative. However, the interaction will actually be fairly limited, as the game is so on rails and the concept so literal that the player might not have any more sense of grand freedom than a player in Kinect Adventures minigames.

The balance of interaction and narrative has never been particularly resolved, but it’s even more challenging in game environments where forward motion is one of the most difficult aspects to simulate–even in Child of Eden, actual “movement” is controlled by the game, and the player has very little control as the game marches forward. In a less abstract and flowing world, this limitation can be particularly annoying as it makes interacting with a full range of the setting or making meaningful choices much harder.

Another challenge all of these games have to face is one of expectations: a Kinect Star Wars title will not have the flexibility of a controller-based version at this stage. Precision gamers seeking to avoid the arm-flailing experience of later levels of Child of Eden will likely seek solace in the traditional controller. But this is in part because the controller is the interface we’re used to: another set of titles in production for the Kinect hope to change exactly that.

Several upcoming games for the Kinect seek to capitalize more strongly on the child-audience already identified by games like Kinectimals, which featured the frankly creepy advertising campaign trying to lure parents to a platform that as of now still doesn’t have much child-friendly followthrough.

The E3 preview of the upcoming Once Upon a Monster shows a child-ready game worthy of the already awesome legacy of its designer, Tim Schafer. Tim Shafer is known for Grim Fandango, Monkey Island, Day of the Tentacle and Psychonauts–some of my favorite games ever made. The playful interface design shown here for kids is some of the most fun yet demoed on the Kinect. It’s marketed as an “interactive story book”, drawing from the same concepts as are currently making waves on the iPad but in a way that makes use of the Kinect’s interface and the potential for cooperative play with parents.

(And, because it is Sesame Street, it is assured a crossover audience of nostalgic adults–like, say me.)

A last E3 title worth remember is Disneyland Adventures, a Kinect-based experience of the theme park. The early previews aren’t showing the narrative, other than the experiential stories already embedded within the themepark. However, there’s a huge potential waiting in this direction–for ideas of where it could go, check out Ridley Pearson’s Kingdom Keepers series, which imagines the adventures of children within the theme parks taking part in a battle between the good and evil characters who give the place its magic.

There are so many stories in these spaces waiting to be probed, and the Kinect’s touch-based interface has already been accused of being child’s play. As the children playing with games like these grow up, what sort of interfaces will they demand for both work and play? And what stories will they tell as motion becomes another tool in an interactive experience and not a gimmick best suited for fitness and dance?