Future Fragments: Always the Bridesmaids

Written by: Anastasia Salter, Pop-Culture Editor

Melissa McCarthy has received a well-deserved Oscar nomination for her surprising supporting role in Bridesmaids. More surprisingly, this feminine twist on traditionally male comedy turf is up for best original screenplay. What made Bridesmaids Academy material, particularly given the usual prejudice against comedy? A surprising self-awareness. In the wake of the “real life fairy tale” wedding, brides are in. But marriage itself is an old-fashioned institution, as a ceremony like that can only remind us further. And even as culturally our values move slowly forward (ok, or at least we hope they do!), marriage is often a step-behind, particularly when race, gender or sexuality is on the line. The two sides of the gender binary stereotypes are particularly played out in the romantic comedy genre, where such clichés can seem inescapable. So when yet another movie with white and pink dresses and wedding-obsessed women pops up in the theaters I tend to avoid the entire ruffles and lace filled affair. (I feel rather the same way about the non-theatrical kind, if there even is such a thing!) But the latest rom-com white dress worship movie surprised me into wondering what the future is for the world of weddings, and how movies like this one might be offering a glimpse of an important conflict that goes beyond placesettings. Why are we stuck with these stories of weddings to begin with? And what’s the future for “happily ever after”?

Disney has always promised us that weddings are what happy endings are made of–they even have an entire side-business in making those wedding dreams come true. Even recent (and slightly more postmodern) Disney flicks have their bridal scenes. The “prince” in Enchanted may have made fun of “true love’s kiss,” but that doesn’t stop him from using one to save his future bride. The Princess and the Frog might have been temporarily resigned to their new fate as bayou dwellers, but the wedding kiss restores them in a magical transformation. Even the action-ready heroine of Tangled settles down at the end of the film as a voice-over informs us that yes, of course they got married.

Judd Apatow’s Bridesmaids manages to do something a bit new: it’s a movie set on the pre-wedding circuit where the men are as voiceless as the women usually are. And in the end, it’s more The Hangover than 27 Dresses. As I was watching, I played match up the character archetypes and found most of the lot had a one-to-one male counterpart from that particular comedy. So is this The Hangover in drag? And if so, is that even a step forward?

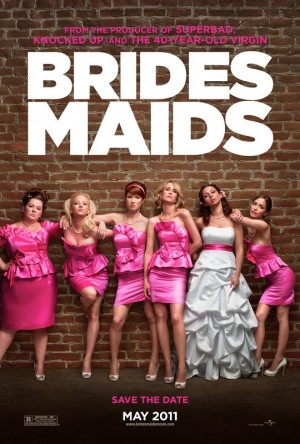

It’s definitely a step up from male-centered wedding flicks. But it’s not for it’s depiction of gender that Bridesmaids earns its props–just take a look at the poster and it’s clear that in some areas it’s taking a few steps back, with the matron-ready bridal gown for the plus size actress at the ready. The relative agency in the flick is thankfully with the women, as is particularly clear in one scene where the newly-engaged bride to be is on the phone with her fiancé and his voice goes mostly unheard as the lives of the women move forward instead. (This is the counterpoint to films like Sideways, which achieved great success despite incredibly chauvinist themes.)

But there’s another struggle brewing in Bridesmaids–the reality of differences in economic class. It’s rare for mainstream romantic comedy to do more than skim over the surface of what it means to be the poor friend. One episode of Friends, “The One with Five Steaks and an Eggplant,” stood out strikingly from the surrounding season for actually highlighting the awkwardness that ensued when some of the crew couldn’t afford to take part in the planned birthday celebrations. One particularly painful moment involved the “rich” friends offering to join them in a patronizing manner, then not understanding the others’ offense. The show only lingered on the true tension for a moment, but it was perhaps most remarkable because class and money remain a charged battleground. Roseanne Barr just pointed out as much in her interview in the NY Magazine that her show remains the great working-class sitcom, and perhaps “even more ahead of its time today”: and Roseanne gave Judd Apatow his first writing job. The continual thoughtfulness of his films reminds us that this start is no coincidence. Take a stroll down memory lane and remember for a moment all the things Roseanne gave us–many of which networks still avoid addressing.

This is no coincidence–the struggle in Bridesmaids is not that of a Pretty Woman trying to fit in among wealthier peers, though it does threaten to start out that way. The moments that highlight such tensions are all the more striking because they are not normally addressed in this genre, even though such tensions are clearly on the rise. The heroine in Apatow’s world is talented, motivated, and even a former entrepreneur who couldn’t make a business work in a recession. She didn’t lose her financial security through stupidity or apathy, which is a refreshing turn that rejects the binary of failure and success that remains an ever-present consequence of the pseudo-equality of the American Dream. She may have a life that’s gone out of control, but she pushes forward and tries to participate in the over-the-top to the point of offensive pre-marital rituals of her friend’s upward rise. These shifts make it perhaps one of the most realistic movies to hit the mainstream theaters this summer, and that despite some tendencies to over-the-top humor that are occasionally regrettable.

Perhaps most tellingly, the Bridesmaids doesn’t make it to Vegas, and the real struggles here put the money-centered conflict in The Hangover into sharp focus:

So even as the over-the-top wedding reminds us that the rich throw better parties, I couldn’t help but sympathize with the bride’s father, plaintively exclaiming that he’s not paying for this as the circus grows even more out of control. The spectacle of the wedding remains hypnotic, and the subject of matrimony is not going away from our collective attention anytime this century. But the need for ceremony of this level right alongside a friends’ financial ruin colors the note of celebration, and the idea that any such excess leads to a “happily ever after” is nicely cut off by the reminders that the marriages of the rich friends are just as screwed up as anyone else’s. This is not a fairytale wedding to buy into, and for that reason alone it’s a nice antidote to movies like 27 Dresses, where reaching the big ceremony is equated with the pinnacle of happiness. Perhaps, as the economy shifts even further, our formulas for happiness are destined to shift with it.