Future Fragments: A Grown-Up in the Hundred Acre Wood

Written by: Anastasia Salter, Pop-Culture Editor

When I traveled through England a few years ago as part of a graduate study abroad program, everyone was asked what they were most looking forward to in British children’s lit landmarks. For me, one stood over all others: a visit to the real Hundred Acre Wood. We drove through a confusing set of roads, getting hopelessly lost for hours in search of the original playground for A.A. Milne’s imagined crew. When we finally found it, it was simultaneously unremarkable and magical. We even played poohsticks on the now-famous bridge, watching our twigs move very slowly to the other side, often getting stuck in the accumulated mass of sticks from other Pooh fans.

When I traveled through England a few years ago as part of a graduate study abroad program, everyone was asked what they were most looking forward to in British children’s lit landmarks. For me, one stood over all others: a visit to the real Hundred Acre Wood. We drove through a confusing set of roads, getting hopelessly lost for hours in search of the original playground for A.A. Milne’s imagined crew. When we finally found it, it was simultaneously unremarkable and magical. We even played poohsticks on the now-famous bridge, watching our twigs move very slowly to the other side, often getting stuck in the accumulated mass of sticks from other Pooh fans.

So when I heard Disney was revisiting its Winnie the Pooh franchise, I was both excited and deeply concerned.

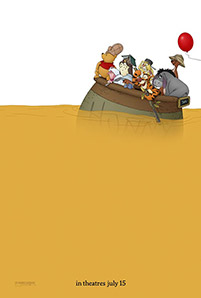

Disney’s Winnie the Pooh movie is in theatres now, and I am relieved to say it is the first truly classic Pooh story in a long time. And with so many collective memories invested in the history of Pooh, it’s a relief that they resisted the temptations of 3D and hip humor and instead stayed true to a story of a boy and his lively stuffed animals. Many children’s movies of late trade heavily on their cleverness. Every moment is laden with pop culture references and jokes that adults in the crowd are supposed to get, while children are intended to be entertained by the sheer absurdity of it all.

Shrek, for instance, used jokes based on Disneyland, constant quips about the king’s height, and music video style sequences filled with visual puns. The wit of Pooh is more subtle, the gentle play on the pretentious pseudo-intellectual Owl, the reliable grouchiness of Eeyore. The most impressive part of the new film is a striking animated sequence midway, involving a strange musical sequence set against chalkboard-art animated in a style that crosses between the chalkboard drawings of a prodigy and classic Pooh. The child is always present: Winnie the Pooh’s world is not for us grown-ups, we’re merely allowed to be observers.

While most of the audience consisted of parents toting children not much taller than Christopher Robin himself, I wasn’t the lone twenty-something drawn back to remember my childhood. The music that plays over the trailer makes a poignant tug at nostalgia. The film may lack the obvious dual-audience appeal that the Pixar films have recently achieved so effortlessly, but there are moments of the same self-awareness, as when Christopher Robin reminds his friends that it is fall, and he’s started school. Us adults know that this is the beginning of the end–we don’t need a Toy Story flash forward to see the inevitable.

In preparation for the film’s release “The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh” ride at Disney World was refurbished with added digital elements and interactive “walls of honey” in the queue outside. The new version is still mostly analog, with one particularly trippy scene involving Pooh’s dreams of honey. The book shares the narrative throughout, and the blustery day blows the words right off their pages.

Winnie the Pooh is the very first book that Apple bundled with the iPad. It was a bold choice, and a reminder of what the iPad had that ebooks at the time did not–the ability to share those same charming illustrations that are now imprinted on our collective consciousness. The image of Winnie the Pooh on the iPad was one of the most common first impressions of the tablet, and children now may well encounter the stories first on these devices.

But while the digital world offers its allure, the physicality of Pooh is well intact thanks both to the books and the stuffed animals themselves. The opening sequence lays out an era-appropriate bedroom, complete with the well-worn animals which (unlike the toys Disney will mostly sell to the movie’s fans) look homemade and soulful. And, aware of the nostalgia some adults felt upon seeing those carefully crafted animals, Disney has even made a limited-edition version of the set itself available.

Disney’s version of Pooh remembers that the books are first and foremost. Some of the most magical moments in all the Pooh experiments are delightfully meta—in this version, the narrator begins by addressing Pooh, trying to get him to wake up by shaking the book. The codex survives: Pooh has even made the leap to iPad app in a puzzle book following Pooh’s quest for honey. As laments still question the fate of reading in a digital age, Pooh seems to be a survivor, a character who can keep his heart against any platform while always drawing us back to the pages from which he sprung.

There are plenty of grown-up biases we can bring back to the Hundred Acre Wood. Frederick Crews’s Postmodern Pooh and the Pooh Perplex offer a gentle mockery of those who would bring adult philosophies and theories to bear on the innocent texts. But at the same time, the countless variations on works such as The Tao of Pooh are a reminder of how deeply these stories can resonate for adults. The wood may be a child’s fantasy, but it is always viewed through an adult lens—Milne himself was guilty of the romanticism that distance affords us all.

But in the end perhaps the highest praise that can be heaped upon Disney’s new film is that while adults may be in the theatre, they are never the ones the film seeks to entertain. For some child viewers, this film might well be the introduction (though hopefully not the last trip) into Milne’s “100 Aker Wood.” It is a beautiful journey.