From Novel to Game: Adapting a Story into a Playable Format

Written by: Tony Lazlo, CC2K Staff Writer

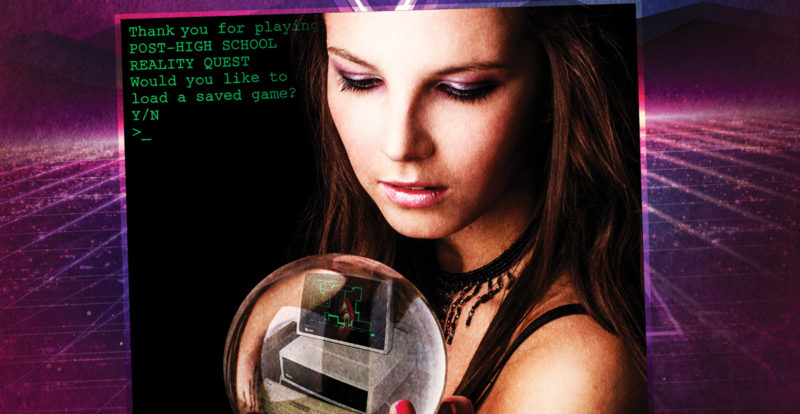

Some movies are adapted into films–but this novel was adapted into a playable game! Meg Eden’s novel Post-High School Reality Quest plays with the classic text adventure game format in its second person narration, and revolves around the dialogue between player and game. This inspired Eden to collaborate with her developer husband Vincent Kuyatt to transform the first chapter into a game!

We at CC2K interviewed them about this process, and the inspiration behind this project.

Q: So what was the inspiration behind this novel, and this process?

Meg: When I wrote my novel Post-High School Reality Quest (PHSRQ for short), I was inspired by a few games. The first was the game Stanley Parable. If you aren’t familiar with it, it’s a game that plays with the concept of games. You start out as Stanley, navigating your office. As you play, you realize the narrator is narrating your actions, and that you have a critical choice to make as a player: to obey or disobey what the narrator is telling you to do. The temptation most players give into is to defy the narrator, which leads into all sorts of wacky, bizarre discoveries, as well as engaging gameplay.

The other inspiration came from Parsley games, particularly one called Action Castle. What is really interesting about the Parsley games is that they are interactive, live-action versions of text adventure games. One person plays the text parser, and the rest of the people play as players, inputting commands. My friends in high school loved these Parsley games. A few of my friends were on the improv team and loved playing the text parser, coming up with clever responses to absurd commands. They made the text parser into its own character, the way a DM brings personality to a D&D quest–and this is something that definitely resonated with me as I wrote Post-High School Reality Quest.

I wanted to have an engaging feature to book launch events–something more than a traditional reading, and the idea of a playable “demo” fit this perfectly. Thinking about Parsley games, my husband Vince and I asked the question: why not make the first chapter of Post-High School Reality Quest into a live-action, playable and interactive parsley-esque game? So we did.

We’ve hosted playthroughs of PHSRQ at conventions including Awesome Con and MAGLabs, and continue to host them at a range of venues. Each time we do it is fun and different, as the player contributes to the formation of the story.

Q: Why text adventures? What do you love about them?

Vince: The abstraction of text is powerful. It allows for the mind to take over and fill in a lot of interesting details. Scary things can be scarier, beautiful things can be imagined to be more beautiful than they might be when visually rendered. This is the same reason why novels are still popular.

Also, the form is one that I feel is underused and deserves more exploration with the modern, extremely fast computers that we use to make and run games. You can do a lot more when you focus on creating the mechanics of the world versus wrangling all the complexities of displaying a game 60+ times a second, and creating the art that goes along with the game. Dwarf Fortress is an example of a game that still renders itself purely with various letters like games used to do when computers only had a few kilobytes of RAM, but has the most complex world simulation of any game to date because that’s all the designers are focused on making.

Meg: When writing PHSRQ, I found the text adventure structure really helped me generate material, and for all of the pieces to come together. As I added the text adventure structure, the text parser became its own character. The text parser is narrating Buffy’s life like a game, and Buffy is inputting commands that the text parser sometimes allows and sometimes refuses. The text parser knows how Buffy needs to play to beat the game, but Buffy doesn’t always want to do what the text parser recommends. This creates a problem for Buffy: she doesn’t appreciate this text parser trying to tell her what to do and wants to escape from a life of being narrated by him. As this form became so critical to the novel, it only made sense to use it as inspiration for the game’s structure.

Q: What were the challenges and rewards in the act of “translation”?

Vince: Fortunately for me, converting prose to a game mostly involves a lot of copy-pasting… at least at first! PHSRQ already apes being a text adventure, so the initial work was pretty much just taking that text and putting it somewhere a bit more structured for handling a text adventure. I forget what I did first, but I believe my initial work was to start adding in some branches or notes on where branches should happen in the first chapter in a Google Doc using a bulleted list. At some point I used Twine to try and make it into an actual game, and I don’t remember if I tried that first or second.

It started to get more challenging when I really started fleshing out the initial draft of what things you could do, easter eggs, what rooms existed and where, who was in those rooms, etc. A book is inherently a linear activity: you go from point A to point B and there’s no diverging from that. So adding in places where the player can choose which direction they want to go, which interactions they should be allowed to have and where, begins to get a lot more complicated.

It’s particularly hard for this conversion, because my main idea was to allow the players to kind of do whatever actions they want, because they’re interacting with a human “parser” rather than a machine. So I tried to come up with every possible little thing that the players could attempt to interact with or do and add in notes that something needs to get fleshed out, or attempt to add that in myself and leave a marker for Meg to go to that place and make the writing actually good and clever. Of course, there’s no way I was able to predict everything, so we got some “beta testers” to play the game and tell us where they got stuck, or have them try things we would never have thought of. There are multiple easter eggs in the demo that were the result of friends doing something wacky.

I would say the hardest challenge of all though was figuring out how to convey what the player should be doing. To us, it was obvious what you generally needed to be doing, but our beta testers kept getting confused and wandered around, unsure of what to do. Because of that, we’ve built in a number of “mechanics,” which usually amount to me [as the text parser] being incredibly sarcastic about something, to convey a hint of what they should do, or add some text to give the players a goal. It’s easy to get wrapped up in your own head and think things are obvious, when they really, really aren’t.

Meg: Yes–I found myself gaining a massive amount of respect for game designers and the incredible challenge they have of leading a player without making the player feel led. As a writer, the path I create is linear. The reader has two choices: to read the next line, or to put the book down. But in designing a game, we had to be really cognisant of all the possibilities, and what sort of clues we had that were “leading on” the player to what they think they’re supposed to do or not do. What seems obvious to the creator isn’t always obvious to the user. A lot of beta players didn’t see a clear “objective” of what to do and goofed off. I found this very helpful as a writer to get this feedback, as I’m horrible at plot. It made me think: what objective am I giving the reader on the first page? What do they think the goal is, and what sort of assumptions are they making about what will happen? What is hooking them to be invested in reading, and guiding them through the page?

Another thing that’s been interesting about PHSRQ is that it’s made us interrogate the strengths and weaknesses of both mediums: what can the novel do that the game can’t? What can the text adventure game of the novel do that “normal” narration can’t?

Q: Has PHSRQ inspired you with some future projects?

Meg: It’s definitely made me think about the power of the natural object, as well as storytelling at large in a new way. This inspired my next novel (currently under edits) which is composed of found objects. I thought about games like The Last of Us and Gone Home where you learn so much narrative through the objects. So I thought, why not narrate a novel through environmental storytelling? I started asking myself questions like: what would be the objects a player would naturally encounter if the novel was a game? It definitely got me thinking in a new and different way.

Vince: PHSRQ was definitely an inspiration for me to try and make a text adventure with Smallworld Online for Ludum Dare: a “competition” which challenges you to make an entire game by yourself in 48 hours. I think that had been around the time that I was working on converting PHSRQ into a text adventure, so I really felt a strong urge to follow my wife’s example and make one for myself. So I ended up writing a small text adventure simulating being in an MMO, and attempting to talk a little bit about addiction to video games by using prompts from the real world such as message or email notifications. Especially because of the time constraints imposed on you for Ludum Dare, I really wanted to work on something that would be easy to put together and I could focus mainly on implementing interesting things rather than creating art or perfecting something finicky like a jump or collision handling.

Want to join in on the fun? Check out upcoming events for the PHSRQ demo, or watch a playthrough of this game at 2017’s MAGlabs “demo” here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DNhbP5X5tRA&t=206s

Meg Eden teaches creative writing at Anne Arundel Community College. Her “text-adventure” novel Post-High School Reality Quest is published with California Coldblood, an imprint of Rare Bird Books. She writes about the intersection of storytelling craft between writing and game design (particularly environmental storytelling), and how nostalgia and retro aesthetics impact how we play games. Unlike her husband, she loves walking simulators. Find her online at www.megedenbooks.com or on Twitter at @ConfusedNarwhal.

Vincent Kuyatt is a developer and tabletop designer in the DC area. His game Smallworld Online was created during the 2017 Ludum Dare, and his game Global Crisis was awarded Best Game Design during the 2015 Global Game Jam at MAGfest. He has spoken at conferences including: RetroGame Con, Awesome Con, KameCon, and MAGlabs. His interests particularly include: 2D vs 3D game design, unreliable narration, form in video games, and using games to teach players real-life skills through engaging mechanics. Find him on Twitter at: @FreezerbrnVinny

Disclosure: Former CC2K editor Robert J. Peterson (Tony Lazlo) is Meg’s publisher through his company, California Coldblood Books.