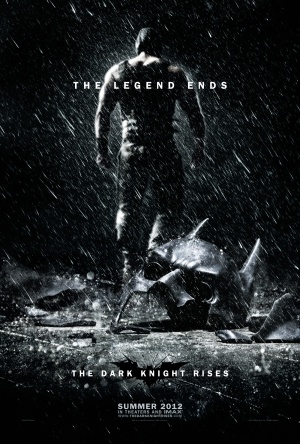

Forces of Nature: The Dark Knight Rises and Its Portrayal of Violence

Written by: Jacob Kunnel, Special to CC2K

With the ongoing media coverage around the Aurora shootings and its survivors, it is interesting to see how almost no one is talking about a potential relation between the media images of the horrible shooting and the violence portrayed in Christopher Nolan’s Batman universe. Yes, we are tired of talking about movies influencing violence and violence influencing movies. And as film makers and -lovers we know very well that movies can’t be made responsible for anyone’s act of violence. There are many reasons why, but, to me, the most valid is that as a filmmaker you have to put so much passion and love into the process of making a film that even the most violent films will have something positive and uplifting to them. Let’s be honest: Most films are made with the best intentions, even if they fail to entertain or provoke any ideas.

With the ongoing media coverage around the Aurora shootings and its survivors, it is interesting to see how almost no one is talking about a potential relation between the media images of the horrible shooting and the violence portrayed in Christopher Nolan’s Batman universe. Yes, we are tired of talking about movies influencing violence and violence influencing movies. And as film makers and -lovers we know very well that movies can’t be made responsible for anyone’s act of violence. There are many reasons why, but, to me, the most valid is that as a filmmaker you have to put so much passion and love into the process of making a film that even the most violent films will have something positive and uplifting to them. Let’s be honest: Most films are made with the best intentions, even if they fail to entertain or provoke any ideas.

While a discussion around The Dark Knight Rises’ connection to the Aurora shootings may be tiresome, since only the press had seen the film before the day of the premiere, it might be interesting to see what kind of violence is presented. There is no hidden statement in this essay, it’s just meant to be a stream of questions – something that opens up a discussion many people seem to be afraid of. To me, this is a necessary discussion because I can’t deny that there’s a certain familiarity between James Holmes’ appearance in court and Heath Ledger’s Joker in The Dark Knight – or between the shooting itself and certain moments in Nolan’s Batman films such as Ras al Ghul’s destruction of Wayne Manor in Batman Begins, the Joker’s attack on Harvey Dent’s party in The Dark Knight or Bane’s attack on the stock market in The Dark Knight Rises.

The question I’d like to ask is not: Is the violence in these films harmful or not but do we, the audience, really like the way violence is portrayed in these films?

Specifically in Dark Knight Rises, Bane (Tom Hardy) is almost used in the same way that the Joker of The Dark Knight was – a character that now seems to be the definition of a blockbuster villain. Both villains are created to be a force that appears out of nowhere and attacks the city several times in moments of complete horror. With that being said I wasn’t really sure what impact Bane’s use of violence in The Dark Knight Rises was supposed to have. Not because the film was PG-13 but because it was the lack of a coherent emotional focal point, and the lack of a human logic to the violence. Bane’s attacks, similarly to those of the Joker, just appear out of nowhere – like an earthquake that hits Gotham over and over again.

As Jett Loe and Gareth Higgins of The Film Talk pointed out in their discussion of the film, the possible reasons for the shooting in Aurora are – as many similar acts of violence – not publicly discussed in a way that people search for resolutions. Instead, shootings like this are seen almost as natural disasters. A force of nature that one can’t anticipate and that, in the end, you just have to deal with. Isn’t this exactly the way Bane is portrayed?

The film is indeed a cinematic opera, and ultimately sacrifices character for world building – something that has become more and more dominant in Nolan’s work since The Prestige. The problem with these huge world building ambitions and the fragmented storytelling is that the film fails to discuss the violence it shows, because it can’t manage to show it through a coherent human angle. Sadly, unlike Bane it was the Joker that gave The Dark Knight a life; that made it a free-floating film. Other characters like Bruce’s love interest Rachel, played by Maggie Gyllenhaal, or Aaron Eckhart’s Harvey Dent, followed a more operatic logic. They existed to make their point, to give a speech about the themes of the film or to drive the plot forward. We do understand them but the screenplay never elevates them into real human characters, which is a pity, because the actors behind the roles are so talented. There’s a lack of impact in Rachel’s and Harvey Dent’s deaths in The Dark Knight that’s quite symptomatic to how death is portrayed in Nolan’s Batman films. It’s this operatic logic that, to me, is essential to the portrayal of violence in The Dark Knight Rises. In comparison to its predecessors, the canvas of this final chapter is blown up to a new level, which lets Bane’s impact appear to be much more fragmented in comparison to the Joker. It becomes an overbearing desire to discuss social themes with the authority that bombastic images will give you.

The film is indeed a cinematic opera, and ultimately sacrifices character for world building – something that has become more and more dominant in Nolan’s work since The Prestige. The problem with these huge world building ambitions and the fragmented storytelling is that the film fails to discuss the violence it shows, because it can’t manage to show it through a coherent human angle. Sadly, unlike Bane it was the Joker that gave The Dark Knight a life; that made it a free-floating film. Other characters like Bruce’s love interest Rachel, played by Maggie Gyllenhaal, or Aaron Eckhart’s Harvey Dent, followed a more operatic logic. They existed to make their point, to give a speech about the themes of the film or to drive the plot forward. We do understand them but the screenplay never elevates them into real human characters, which is a pity, because the actors behind the roles are so talented. There’s a lack of impact in Rachel’s and Harvey Dent’s deaths in The Dark Knight that’s quite symptomatic to how death is portrayed in Nolan’s Batman films. It’s this operatic logic that, to me, is essential to the portrayal of violence in The Dark Knight Rises. In comparison to its predecessors, the canvas of this final chapter is blown up to a new level, which lets Bane’s impact appear to be much more fragmented in comparison to the Joker. It becomes an overbearing desire to discuss social themes with the authority that bombastic images will give you.

The implication of such a portrayal of violence as this is that it lacks any origin. Although Bane explains why he’s attacking Gotham, the violence is defined through his in-the-moment quality, almost as if he was Breaking News on TV. It’s as if the violence of Bane is a simulation of the way news magazines cover catastrophes and terrorist attacks, with one major difference: Those news stories have an origin, a story behind the story. In the superhero-logic, this history of violence is exchanged with the antagonistic talent of the villain. Bane is presented as a superhuman being, a force of nature whose violent behavior doesn’t need an origin. While this portrayal of the villain is similar to that of The Joker, it made better sense in the world of The Dark Knight. With The Dark Knight Rises, it’s much more problematic, because this use of violence is less an interruption of the norm; it has become the norm.

This villainization of violence becomes a problematic thing – and it’s not something that only happens in superhero movies. It’s something that is as old as the history of media and we’ve all experienced it when reading the newspaper or watching the news. Dictators are presented as the only reason why we are fighting World Wars; psycho killers are the only reason why there is gun violence. It’s an obvious and over-simplifying strategy, but these images also help us to better understand conflicts, to develop our moral values or to motivate people to fight for a good cause.

For The Dark Knight Rises, it’s a more digestible way to use the power of violence: Only the villains can use violence with an impact and these events are the major beats in the screenplay. While the heroes can use it, it comes without any real positive or negative impact. When police officer John Blake (played by Joseph Gordon-Levitt) reluctantly shoots two criminals, he’s portrayed as a good cop, but the idea that he has just killed two people has no further consequences to him or the film‘s storyline. To a degree, the good or “normal” people of highly corrupt Gotham are infantilized in these movies because they are not able to use violence that has any impact. I understand the concept of non-violent civil disobedience (as shown in the scene with the two ferries in The Dark Knight), but it is not supported by the film itself, because this is not what saves the day in the end.

The Dark Knight Rises tries to articulate a concept of resistance, but by portraying Bane’s violence as a force of nature, it basically refuses to open up a discussion. The film is not about how to deal with the violence and to collectively fight it, it’s about the idea that we somehow have to deal with it. In Nolan’s universe, the question of moral and physical power are closely linked to the amount of violence someone uses. If in this universe, violence is exclusive to the powerful villains, who unquestionably have the greatest impact on the story and the world of the film, can you – vice versa – only stand out if you use violence as a tool to gain impact?

It’s a rhetoric that has invaded popular culture for a long time – and more prominently after the terrorist attacks of 9/11. It might be a major reason why Batman Begins and The Dark Knight resonated with audiences. If Batman Begins is the hypothesis on how a city or society deals with outside forces of terror, The Dark Knight is the argument and The Dark Knight Rises is the final statement. That last statement might be the least interesting part of the three. Popular culture, might it be comics or superhero films, can have an impact if they raise questions through a fictional setting and if they show us connections that we didn’t know had existed. The Dark Knight Rises seems to promote the idea that the violence of this fictional setting, a simulation of news images, is the way violence generally works – as a force of nature.

Is this something we really agree with?