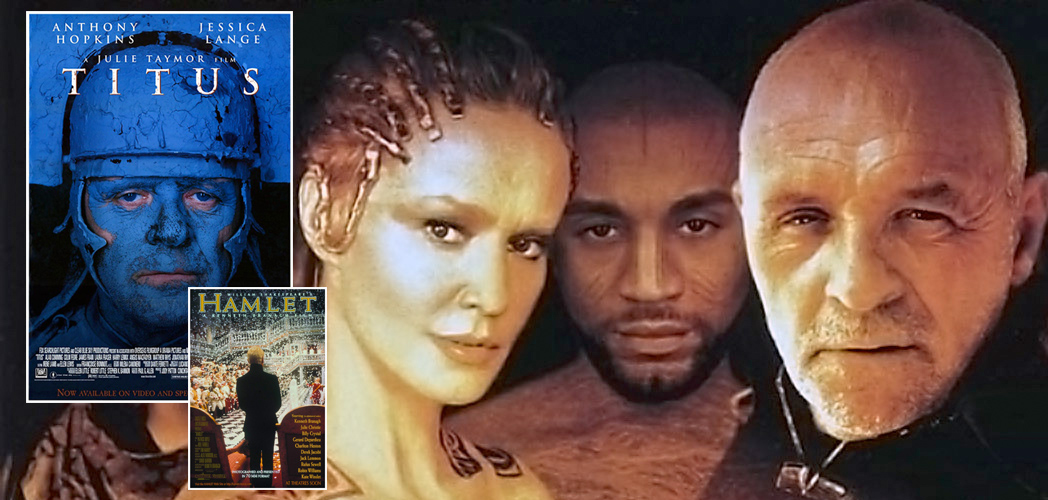

Everything But The Kitchen Sink: Julie Taymor’s Titus and Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet

Written by: Tony Lazlo, CC2K Staff Writer

Everything But The Kitchen Sink is a burgeoning genre these days, what with the advent of high-octane, Jerry Bruckheimer blowouts that blitz us with two-and-a-half-hour marathons of movie stars doing the heroic squint, indie actors slumming for a big paycheck, and Aerosmith banging out some more hoary rock ballads. But Bruckheimer and his retinue don’t know how to make a truly great Everything-But-The-Kitchen-Sink (EBTKS) movie. Ideally, an EBTKS movie manages to qualify less as a typical film and more as some bizarre half-breed of traditional narrative and pornography, though they need not always be packed with hard-core fucking. Yes, oftentimes EBTKS movies will feature explicit sex – Caligula, for example – but in other cases its excesses are relegated to extreme violence and ultra-vulgar humor – Bad Boys II, for example, which was financed by Bruckheimer and which sprang from the twisted mind of the master pop-vulgarian himself, Michael Benjamin Bay.

And by invoking Bay’s name, I don’t mean to suggest that EBTKS movies are always bad. Far from it. But I submit that to make a great EBTKS movie requires far more creative discipline than the Bruckheimers and Bays of the world could ever hope to have.

Already Taymor’s made her point: Be ready for anything. She wisely sets her movie on another planet – one that resembles our own, but whose eras have bled together like bloody watercolors. More examples of this: Chiron and Demetrius, the twin-raping sociopaths, wear leather, smoke and drink and play violent video games. When Titus gets his hand chopped off to give to the emperor (don’t ask), the deliveryman (the evil Aaron), drops the severed hand into a Ziploc bag and hangs it from the rear-view mirror of his Mustang.

Again, as much as the pan-epochal setting facilitates her Everything-But-The-Kitchen-Sink ideas, her psychotic, hopped-up, EBTKS interpretation helps pull the play out of the Ovidian mess it wallows in and clarify its themes: violence begets violence (yawn); “Rome is a wilderness of tigers” (double yawn); and further under the surface, the importance of family over all.

Granted, Peter Brook directed a legendary production of Titus Andronicus for the RSC in 1955 that featured none of the hipster-avant-garde bells and whistles that Taymor employs, and his production was a smash hit. Now before you jump to the conclusion that I’m going to argue that Taymor had to pander to a modern audience, let me say that Taymor doesn’t dumb down the play. Not even theater great Trevor Nunn could resist adding a “this is for the idiots in the audience” expository speech to the beginning of his film version of Twelfth Night. Taymor makes no such dubious additions, and furthermore, she doesn’t resort to the Baz Luhrmann method of directing Shakespeare, which is to cut more than half the text and cast a matinee idol in the lead who can’t handle the text anyway. Don’t get me wrong; I love the Luhrmann Romeo and Juliet, but I applaud Taymor for hiring a uniformly excellent cast and sticking to the text. Purists flipped out over Taymor’s “non-traditional” adaptation, but I wonder if they had read the play. She cut virtually nothing. Hell, I don’t think she cut enough. Do we really need to hear any of Marcus’ incomprehensible speech in reaction to finding his niece raped and mutilated, especially when a film can show his reaction better than a shitty early Shakespeare speech ever could? No, we don’t. Add to this textual fidelity Taymor’s batshit imagery – all of which serve to underline the play’s trippy, psychotic atmosphere, which in turn serve to underline the play’s themes – and you have a well-conceived EBTKS vision.

Side note: As much as I wish I could have seen Brook’s legendary production – which starred Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh in the midst of a messy offstage divorce – part of me wonders if Brook’s elegant, bloodless staging (he used red ribbons to signify gore) would have legs today. Brook did have the benefit of an upper-crust audience (rich Londoners who could make the two-hour trip and afford tickets to the RSC), and I believe thatTitus Andronicus begs for a director to un-fuck its problems enough to unleash its strengths: brawny characterizations, black-burlesque comedy and forward velocity. Slow, sober and staid will sink a production ofTitus, whose hectic first act is one 30-page scene and whose climax features four kills in as many lines.

And it is forward velocity that distinguishes Taymor’s movie from many other “great” Shakespeare adaptations. Bursts of insanity propel the manic first act, including one of the film’s so-called “penny arcade nightmares” – interludes of pure visual weirdness. At the end of the play’s first act (roughly half an hour of screen time), Titus and Tamora square off against a backdrop of flame. Flaming arms and legs pinwheel toward the camera. A headless, limbless, but living human torso appears between them and gasps for air. An invisible blade opens a bloody gash across the torso’s chest.

Taymor’s EBTKS approach isn’t 100 percent successful, but all of her crazy images are benevolent symptoms of a director so jittery and aglow with ideas that she can’t help herself – and in any case, I applaud her audacity because Kenneth Branagh tried the same thing with his Hamlet and failed miserably.

In fact, as long as we’re at it, let’s take a look at Kenneth Branagh’s career in Shakespeare. For his first feature film, Branagh unrepentantly takes on Henry V, thereby screaming at anyone who could hear, “I am this generation’s Laurence Olivier!” Keep in mind that not only was Olivier regarded as the greatest classical actor (maybe the best actor period) of his generation, but also that Winston Fucking Churchill himself asked Olivier in 1944 to make a film of Henry V to rally England, which was, of course, in the process of being bombed back into the Stone Age by the Germans.And what does Branagh do? He fucking delivers. He makes a down-and-dirty Henry V; a patriotic and rousing movie that nonetheless retains the cynical, anti-war message that Shakespeare wove into his greatest history play. Olivier made a Henry V for WWII. Branagh made one for the post-Viet Nam era, and he did it with realistic sets (as opposed to Olivier’s oftentimes dollhouse-looking backdrops); naturalistic acting (watch Henry’s “tennis balls” speech in act one to see the best comparison of their acting styles. Olivier gets so big, Zeus has to bang on the floor with a broom handle; Branagh barely raises his voice); and fidelity to the text (Olivier cuts all of Henry’s less-than-saintly moments; Branagh makes them work).

A few years later, Branagh tops his Henry V with Much Ado About Nothing – a fun, energetic romp of a movie that somehow manages to make the play’s lousy melodrama subplot work alongside the classic old-nemeses-fall-in-love-again main plot with Benedick and Beatrice (one of the few storylines in the canon that Shakespeare actually made up on his own, along with most of The Tempest).

What distinguishes Branagh’s first two Shakespeare movies is their generosity. Branagh loves, loves, loves Shakespeare, and he proves in these two films that a great performance of Shakespeare will trump its antiquity and make it accessible to anyone, even if they haven’t read the play.

Then came Hamlet.

Can I even tell you how stoked I was when I popped in my VHS copy of the Oliver Parker Othello (starring Laurence Fishburne in the title role and Branagh as Iago) and saw the super-amazing extended trailer for Branagh’s Hamlet? I’m getting misty-eyed just thinking about it. Branagh had rounded up enough stars to make Irwin Allen proud, including Derek Jacobi, Julie Christie, Kate Winslet, Charlton Heston, Robin Williams, Billy Crystal, Gerard Depardieu, Jack Lemmon, Richard Attenborough, Judi Dench and John Gielgud. Oh, and Aunt May from the Spider-Man movies as the Player Queen. He had filmed it in 70mm at some awesome-looking castle.

And he hadn’t cut one fucking word.

That’s right. Branagh, in his bid to unseat Olivier as Greatest Shakespearean in the Universe, decided to break ranks with Sir Larry (who cut more than half the text in his Hamlet, which won the best picture Oscar) and leave in every word and every subplot, no matter how inconsequential. I mean, Jesus Christ – fucking Voltemand and Cornelius made the cut!

I … COULDN’T … FUCKING … WAIT!

Then … I see the movie. And indeed, it’s filled with many great EBTKS hallmarks: Huge sets! An all-star cast! Slashing, energetic camera-work! Crazy, imaginative cut-aways to stuff like Hamlet fucking Ophelia and scary pirates! Grrr! Arrr!

And the movie sucks. It sucks nards. Donkey nards. Nasty, herpetic donkey nards all dripping with abscess and blood.

It. Sucks.

But why does it suck, you ask? Well, many of Branagh’s EBTKS impulses feel like first drafts. The scene with the ghost of Hamlet’s father – frightening and moving in Michael Almereyda’s modern and frippery-free Hamlet – feels like an Ed Wood movie, complete with fake-looking sets and fake-looking smoke-machine smoke. And why the fuck did Branagh make Brian Blessed (one of his regular players) WHISPER all his lines as the ghost?! Blessed had made his name playing howitzer-voiced, barrel-chested badasses – Exeter in Henry V and the gung-ho hawkman from Flash Gordon, for example – so why waste his talents? Stunt casting? Or another ill-conceived EBTKS impulse?

Stupid choices abound. In the famous “Alas, poor Yorick” speech (the one where he’s holding the skull), Branagh cuts to an image straight out of Kubrick’s The Shining: a bizarre, retarded-looking moppet with fluorescent blond hair is hoisted onto the shoulders of a deranged, monstrous, cackling, grease-painted fat man with eye-teeth the size of trowels. This blubberous creature gogs at the camera as he whips the helpless boy back and forth and sends a jolt of psycho-pain crackling through the audience’s collective neck in fear that this man-beast – Yorick, apparently – might paralyze the innocent, retarded and alarmingly blond young Hamlet.

Suffice it to say, it kills the moment.

And Richard Attenborough? He plays the English ambassador. This guy comes in for five lines at the end and basically says, “What in the living fuck just happened?” (Well, he does give Tom Stoppard an idea for a pretty cool play …)

John Gielgud and Judi Dench? Branagh had the bright idea to highlight Hamlet’s speech about Priam and Hecuba with one of his creative cut-aways, and he apparently decided that the only two of the greatest classical actors of all time – both knights, I might add – could handle these two non-speaking roles.

That said, the movie isn’t entirely worthless. The supporting cast, when Branagh isn’t fucking up their performances, is great. Charlton Heston, a man who made a living being a shitty actor, is astonishingly good as the Player King. Kate Winslet delivers an Ophelia raw enough to rival Bjork’s performance in Dancer in the Dark. Robin Williams is fine in one of those unfunny-but-we’re-supposed-to-laugh-because-it’s-Shakespeare roles as Osric. Billy Crystal plays the only tolerable gravedigger I’ve ever seen. Branagh regulars Michael Maloney (Laertes), Richard Briers (Polonius) and Nicholas Farrell (Horatio) are all excellent.

And even Branagh himself is pretty great in some scenes … and that’s what makes the movie so maddening. Because to see Branagh botch the “To be or not to be” speech with auto-fellating self-importance and then reboot the “We defy augury” speech with galvanizing skill pisses me off more than a million whispering Brian Blesseds, because by not fucking up in some scenes, Branagh unknowingly taunts us with the performance that could have been.

So what went wrong? How could Branagh, who had acquitted himself so admirably in adapting Shakespeare, blow it so entirely?

Simple. And I’ll even dovetail the answer with Titus: Taymor threw in everything but the kitchen sink to elucidate the play’s themes. Branagh threw in everything but the kitchen sink to beat Olivier’s Oscar count. He chose a brightly lit castle – at odds with the play’s paranoid atmosphere – to win an art direction Oscar. He shot it in 70mm to win a cinematography Oscar. He left in every line to win Oscars for acting, directing and picture – not to achieve any legitimate artistic end.

But back to Titus and Taymor’s batshit imagery. This play makes her feel violent and fucked-up, so by God she puts some violent, fucked-up imagery onscreen. It doesn’t matter to Taymor how much sense her imagery makes; she only cares about how it makes her feel.

And her images do make sense. Remember the “penny arcade” sequence with Titus and Tamora staring each other down across a sea of flaming limbs? A look at the text will show that this interlude is a natural outgrowth of the play: Titus and Tamora are two of the play’s power points, and severed body parts are a grisly, often loony leitmotif in the play (one famous/infamous scene has our heroes exiting the stage carrying two severed heads and a severed hand – the latter clenched between poor handless Lavinia’s teeth). Peter Brook tried to pretend that Shakespeare had a deep, serious play in mind, so he replaced all the gore with elegant stagecraft; Taymor, by contrast, knows that Shakespeare had a deranged, bloody fever dream in mind, and that’s what she puts onscreen.

Let’s get back to an earlier point: that all of Taymor’s imagery serves to underline the plays themes. Marching at the head of the vanguard to dismantle this troublesome play is Taymor’s stable of certifiably insane designers. Let’s take one theme, explicitly spoken in the play: Rome is a wilderness of tigers. Shakespeare sets this play in a state verging on anarchy. Violent factions compete for a vacant throne, and when the well-meaning Titus bestows the empery on the older, more aggressive son Saturninus, all hell breaks loose. (Incidentally, in the Titus character we see an early example of a stupid old man who, citing age and infirmity, cedes his kingdom to crazy young people – a character Shakespeare would execute with considerably more power in King Lear.) Taymor and her design team weave animal imagery throughout the film with joyous anarchy: Tamora and Saturninus’ make-up often looks feline; animals pelts complement many costumes (Demetrius wears a tiger-skin coat, Saturninus a suit of armor lined with leopard skin); and in one of the other “penny arcade” sequences, Taymor indulges in some of her most striking – if facile – imagery: Titus’ brother Marcus comes up with the great idea to have Lavinia – left without hands or tongue by her unknown rapists – write out the offenders’ names with a staff held in her mouth and guided with her stumps. Lavinia opens her mouth, decides (understandably) not to take the staff into it, and begins to furiously scrape her rapists’ names in the dirt. As she does, rock music blares from the soundtrack and the picture intercuts with images of Lavinia standing on a Roman column wearing a deer-head-hat (I’m not making this up), while Chiron and Demetrius (her rapists) jump at her, their bodies transforming into tigers. Keep in mind that earlier in the play the two rapists are called tigers and Lavinia a deer. Specifically. By name. And frankly, Lavinia’s deer-head-hat looks pretty goofy. But understand this: Taymor does not give a fuck. Lavinia is in a turbulent state of mind when she writes those two names, and Taymor uses all means at her disposal to put those turbulent feelings onscreen; and by indulging in the craziest imagery that comes to her, she echoes the anarchy that Rome has fallen into.

An affection for old-school, big-entertainment, Busby Berkeley, razzmatazz moviemaking powers Taymor’s anarchic vision. Besides the aforementioned “penny arcade” sequences, Taymor hits us with beautiful locations, stunning costumes, spectacular sets and most important, clever use of anachronism. While campaigning for the vacant empery, Saturninus and Bassianus – the two surviving heirs to the throne – ride in cars and address their followers through old-fashioned microphones. In a truly inspired choice, the fey and ultimately gutless Saturninus speaks from inside a bulletproof Popemobile shield. When Saturninus assumes power, Taymor shows us a wild bacchanalia, replete with blazing jazz, big-titted inflatable beds on a pool filled with naked, dancing bodies and cast-off fruit and champagne glasses. Taymor cherry-picks her images from across the ages, but all show us the same thing: a kingdom choking on its own excess.

Here’s another key theme: The importance of family over all. When she concentrates on this, an actually interesting theme, Taymor really starts kicking some ass. The key character arc that explores this theme involves, naturally, Titus and his children. In act one, he murders one of his few remaining sons in cold blood. In act five, he kills his raped and mutilated daughter in an act of mercy – a 16th-century argument for the virtue of assisted suicide. Taymor doesn’t really do anything spectacular with this plot strand; she wisely stays out of its way. Hopkins, to his credit, finds his greatest control when he delivers the famous “pasties” speech to Chiron and Demetrius, in which he describes how he plans to bake the two rapists into pies to serve to their mother. Taymor could have had Hopkins jumping and shouting all through this great speech, but instead she keeps her camera tight on his face and lets him underplay the whole thing; and instead of balls-out insanity, Hopkins lets honest parental outrage fuel his desire for revenge.

Another freight train of narrative goodness that Taymor wisely dodges: Aaron’s baby. Aaron, the play’s chief villain, tromps around the stage like the usual two-dimensional Shakespearean baddie – as entertaining as Iago, but as deep as Don John from Much Ado About Nothing. But then he fathers an illegitimate child with the empress Tamora, and holy shit, does he change. When Chiron and Demetrius threaten the child (an illegitimate baby would disgrace them all), Aaron draws his sword, grabs the kid and heads for the hills. Later, Titus’ son, the elder Lucius, captures Aaron and threatens the child. Aaron then proceeds to deliver one of the most demented speeches in all of Shakespeare:

Even now I curse the day – and yet, I think,

Few come within the compass of my curse –

Wherein I did not some notorious ill,

As kill a man, or else devise his death,

Ravish a maid, or plot the way to do it,

Accuse some innocent and forswear myself,

Set deadly enmity between two friends,

Make poor men’s cattle break their necks;

Set fire on barns and hay-stacks in the night,

And bid the owners quench them with their tears.

Oft have I digg’d up dead men from their graves,

And set them upright at their dear friends’ doors,

Even when their sorrows almost were forgot;

And on their skins, as on the bark of trees,

Have with my knife carved in Roman letters,

“Let not your sorrow die, though I am dead.”

Tut, I have done a thousand dreadful things

As willingly as one would kill a fly,

And nothing grieves me heartily indeed

But that I cannot do ten thousand more. (Act 5, scene 1)

And he does all this to save his son’s life. Harry Lennix, criminally wasted in the second and third Matrix movies, nails the speech – and more important, he shows us the love that somehow springs from a heart as evil as Aaron’s.

Taymor doesn’t let Aaron monopolize the “family over all” theme, though. First she sets up the younger Lucius (the elder Lucius’ imaginatively named son) as our eyes into this crazy world, and when the elder Lucius orders that Aaron’s child be killed, the younger Lucius saves the child. The movie ends on one of the longest tracking shots in film history, following the younger Lucius out of the coliseum and toward a sunrise, the baby in his arms. A freeze frame worthy of John Hughes – young Lucius, baby in arms, hittin’ the road – caps Taymor’s freshman flick. Awesome.

But Taymor’s exploration of the “family over all” theme achieves true greatness in one non-verbal moment she adds to the narrative. In this scene, the younger Lucius visits a dollmaker’s shop, where he buys a pair of wooden hands that he gives to Lavinia. And damn if she doesn’t wear them for the rest of the movie. Sure, mold and cracks stain and deface the wooden hands, but Lavinia beams at young Lucius all the same. Obviously, this scene is not in the play. Young Lucius doesn’t have that big a part. Taymor looked at all the themes and just thought it up.

That’s great directing.