Echoes and Layers: Tony Lazlo Looks Back at The Wire

Written by: Tony Lazlo, CC2K Staff Writer

It’s another overlong Tony Lazlo screed, everybody! This time I turn my jaundiced eye on season five of The Wire, using that much-maligned season as the entryway to a larger discussion about the series as a whole.

I first watched The Wire, David Simon’s seminal portrait of the city of Baltimore in five acts, a few years ago. I recently plowed through the series again, this time with the foreknowledge that its final season was generally regarded as its weakest. When I first watched the show, I remembered admiring the newsroom scenes, and especially the performance of Clark Johnson as the Sun’s city editor. So did my rewatch confirm or disconfirm the inferiority of season five?

Sadly, it confirmed it.

But as a journalism school grad, a lousy reporter, and a huge fan of the show, I’ve still got a few things to say about it. (Don’t worry — I was only a bad journalist, not a fabulist.)

Before I can talk about why season five was less successful than its four predecessors, I need to try and get a critical handle on why those other seasons — including and especially the fourth — worked. Needless to say, I’m writing in the wake of hundreds of existing (and better) essays and reviews, and I’m doing this for myself as much as for you; I’m learning as I go.

Seasons one and two

After a second inhaling of the show, here’s what I think was key to its success: A novelistic recursion and layering of theme, told with echoing storylines and a cast of characters that graduated from one role to another.

Let me try to break that down: It’s common knowledge that The Wire is only ostensibly a cop show. In season one, that artifice is most evident. The focus is on the special investigative unit that McNulty’s big mouth called into existence, as well as on the drug trade in the projects. The actions of the special unit drive the story, which is built on a foundation of police procedure; sometimes brain-numbingly detailed police procedure.

But season one was also largely about families — figurative and literal — and that theme echoes through all the season’s major storylines; most notably D’Angelo Barksdale’s arc, which depicts his deteriorating relationship with his family, including his literal mother (Brianna), figurative fathers (Avon and Stringer) and figurative siblings (most of the project crew, but primarily Wallace and Bodie). McNulty’s family also figures into the action, given his status as the series’ nominal lead. Like D’Angelo, McNulty’s relationship with his family is falling apart, but for different reasons. D’Angelo spends the season fine-tuning his moral compass, and when he’s forced to confront the sins of his life, he very nearly rolls on his family for the greater good. By contrast, McNulty spends the whole series trying to find his moral compass as a civilian. McNulty’s moral compass only seems to come online when he’s working. The instant he clocks out, he’s an amoral hedonist. (Note: I added “amoral” because I don’t think hedonism is by definition amoral.)

(Side note: I just realized that Michael B. Jordan of Friday Night Lights fame — and our new Human Torch — played Wallace. Cool!)

Moving on to season two: We watch McNulty “graduate” from the special crimes unit to the season’s primary setting: the docks. After crossing his superiors — including A-grade asshole Bill Rawls (the delightfully cantankerous John Doman) — McNulty gets busted to boat-cop duty, doomed to patrol the coastlines. For me, this is the first example of a The Wire “graduating” a character from one season to another, though it’s not the best example because McNulty doesn’t really change. His default setting is as a hard-charging special-crimes detective, and any time he deviates from that, he’s less of a cop, though in season four we see it makes him a better person. Ideally, when a character “graduates” in the Wire sense, they morph into a completely different role; maybe even transforming into a new person along the way. The Wire has several such distinguished graduates. I’ll talk about them later. For now, I want to focus on thematic layering and echoing.

The chief theme of season one, family, carries over into season two, naturally feeding into the story’s exploration of the deterioration of the local unions. But season two isn’t just about families, and it isn’t just about the unions — it’s about union. Loyalty. Sticking up for your own. Union chief Frank Sobotka (a perpetually sweaty Chris Bauer, fiery, desperate and crackling) pays off a desperate worker to keep him in the fold, all while getting in bed with the Greek mafia to keep his union relevant in the face of advancing technology and a globalized economy. Nick Sobotka (Pablo Schrieber from Orange is the New Black) disobeys his father to open up new business with the Greeks in a foolhardy effort to give his young family financial stability. Cedric Daniels (the always stalwart Lance Reddick) cuts deal after deal to reassemble the special crimes unit. Stringer goes behind Avon’s back to get in on Prop Joe’s drug supply to hold together their dwindling share of the drug trade. The theme echoes through all the major storylines.

Unfortunately, none of the major players from season two graduate to any of the future seasons. We see the Greeks again, but it would have been nice to see Nick Sobotka reappear for something important. (We only get a brief glimpse of him in season five.) I guess Amy Ryan stays around, but graduating from “cop” to “girlfriend” isn’t great example of what I’m talking about. There’s also some collateral loss among the show’s themes. Although season one’s theme, family, is felt for the balance of the show’s run, the second season theme of union fades somewhat. The net effect is that season two feels like a hermetically sealed package, with little to no connective tissue between it and the rest of the show. It’s still a great season, though I’d rank it below seasons three and four. (That hermetically sealed feeling also links season two with season five, but I’ll get to that later.)

Seasons three and four

Let’s talk about The Wire’s magnificent third and fourth seasons, which feature the most satisfying examples of thematic layering, echoing and character graduation. Season three introduces a theme so potentially boring it would have sounded death-knell for any other show: management.

On its surface, season three is about the gilded halls of downtown politics, but it’s really about management and, specifically conflicting management styles. City councilman Thomas Carcetti (Aiden Gillen playing a very Game of Thrones-style character) embodies this theme in its most literal sense, mounting a slow-burn challenge against the incumbent mayor. Conflicting management styles also drive the storyline in the projects, where Stringer Bell graduates from drug kingpin to real estate magnate — and pays a steep price for his hubris.(That’s another running gag on this show. In the Wire-verse, you belong to your caste, and with very few exceptions, when you stray outside it, the results are bad — ranging in severity from “simple embarrassment” to “death by shotgun-blast.” Stringer betrays Avon to get out of the drug trade, and he gets blown to bits. D’Angelo takes his girlfriend to an awkward dinner at a chi-chi restaurant. McNulty, in an effort to forge an actual emotional connection with tenacious campaign guru Theresa D’Agostino (Brandy Burre, flinty and intense), foregoes their fuck-buddy sex in favor of an actual date. The result: a meal of high-class condescension for poor, working-stiff McNulty. Just kidding. The asshole had it coming.)

Along with a fascinating theme, season three also features my favorite piece of pure invention in the whole show: Hamsterdam. The brainchild of maverick police major Bunny Colvin (Robert Wisdom, lambent with benevolence), the drug-safe zone is a dazzling thought experiment. It’s almost — almost — too weird for the show’s otherwise neorealistic vibe, which eschews the rhythms and contours of a classical narrative in favor of an episodic experience that better captures the vagaries (and occasional boredom) of daily life, all shot on actual locations with very little flair. Did you ever notice how The Wire has no scored music? Only the occasional rock song highlights key moments. And although The Wire made stars of many of its performers, it mostly featured unknowns, as well as a few non-pros lifted straight from the streets. Felicia Pearson, aka Snoop, remains the most memorable of these discoveries. Pearson, who hails from a tough upbringing, randomly bumped into Michael K. Williams (Omar). Williams landed her the role on the show. Thank Crom he did, because Pearson delivers one of the most sublime performances on a show that’s packed with them.

Here’s an interview with Pearson and Willams:

(For more on neorealism and The Wire, you’ve got to check out this essay over at Dossier Journal.)

Anyway, as realistic as the show is, Hamsterdam somehow works within its confines, no doubt because of the intellectual rigor with which the showrunners examine the causes and effects of such an enterprise. Legalizing drugs is one of those recurring flashpoints for political debates — often a rallying cry of the left, I’d say — and while I don’t know if leftists would want to see heroin legalized overnight, Hamsterdam gives us a compelling look at what such a rapid policy change might look like — messy, imperfect, but effective. (Hamsterdam also carries on one of The Wire’s great ongoing moral storylines: the plight of the homeless. Me, I’d argue that Simon could’ve made the homeless the centerpiece of a future season, but it doesn’t matter — they’re always present, anchored by one of the show’s most gut-wrenching performances, Andre Royo’s Bubbles. Oh, and I’ll talk about ideas for future Wire chapter-seasons later.)

Moving on: Bureaucratic bullshit brings about Hamsterdam’s existence, as seen in another of season three’s depictions of management: the police review boards. Here we finally get to see more of Rawls’ day-to-day worklife, which seems to involve shouting at his underlings and making unreasonable demands. But here again we see more echoes, as Rawls later gets dressed down by the mayor, who in turn gets dressed down by the feds. There’s always a bigger fish. (Side note: I wish we could’ve seen more of Rawls’ personal life, but I feel like the fleeting glimpse we get of him in a gay bar is all we’re supposed to get. Rawls lives his life in hiding, so his character hides from us, too.) The theme of management styles continues to echo through all the major storylines:Colvin’s management style, with its fuck-you-I’m-retiring focus on independent thought and dramatic gestures, ruins his career. McNulty continues to ignore orders, bringing him into direct conflict with Daniels and Freamon. Perennial fuck-ups Herk and Carv continue to do their own thing

But let’s not forget about character graduation, one of my favorite devices in all of storytelling. The Wire does it extremely well, and you can also see some great examples of it in genre fare. On Deep Space Nine, Nog graduates from Ferengi cut-up to starfleet superstar. On Battlestar Galactica, Gaius Baltar graduates from mad scientist to politician to religious icon. Also on BSG, Apollo graduates from the military to politics. (Military stories in general are replete with tales of characters who graduate from infantry to command.) Pivoting back to The Wire, let’s talk about my personal favorite character in all of The Wire: Cutty.

Former soldier Cutty (Chad Coleman) is one of the few characters in The Wire’s universe to graduate roles multiples times in one season. He enters the narrative fresh off a 14-year stint in Jessup, a proven killer with street cred to spare. He starts out as the perfect avatar for the horrors of the drug trade, but fortunately, he’s lost his taste for the Game. He then graduates into the city hall storyline, giving us a first-person look at the red tape that chokes Baltimore’s services. Do I even need to use the word “Kafkaesque” to describe his efforts to get the necessary permits to open a boxing gym? But open the gym he does, after calling in a few favors from some Ballmer bigwigs and hitting up Avon for startup funds.

I could go on at length about Coleman’s performance. He’s been blessed with a kind face and a relaxed onscreen style. He’s never not completely earnest, never not trying to better himself. He also falls into a category of characters that often exerts an irresistible pull on me as a viewer and a writer — he’s a disgraced knight in exile, looking for a cause. Jorah Mormont over on Game of Thrones is one such knight, and like Ser Jorah, Cutty seeks his redemption in a form of education. Mormont strives to be Danaerys’ most trusted adviser, while Cutty morphs from gangland muscle to streetwise coach, heralding the greatness of season four.

So let’s move on to season four, the mightiest of all The Wire’s seasons. Thematic layering and echoing runs throughout season four. The same ideas echo throughout every storyline. Bubbles tries to teach his charge (Sherrod) how to run his own business, and hired killers Snoop and Chris try to teach young Michael the ways of the street. Season four isn’t only about the school system — it’s about schoolin’. Season four also layers itself perfectly into the overall storyline, carrying over season three’s look at management styles. In this case, we see a variety of teaching styles, pitted against the usual bureaucratic “juke the stats” bullshit. Season four’s thematic structure even echoes backward into season three through Cutty and Bubbles, a pair of unlikely teachers.

In addition, season four features two of The Wire’s most distinguished graduates: Colvin and Prezbo. After getting fired, Colvin joins forces with a big-hearted nonprofit, morphing from police lieutenant into hard-hitting teacher. The nonprofit selects 10-12 problem students for a special education program that’s essentially longform therapeutic analysis. The class has a lead teacher who handles the bulk of the talk-therapy, but Colvin provides the heart of this storyline. He forges a deep, loving bond with his students, taking Namond (son of jailed soldier Wee-Bey) under his wing.

The showrunners also distantly echo the Hamsterdam storyline in this special classroom at Tilghman Middle. Just as Hamsterdam quarantined the city’s most troubled population, Colvin and program head Dr. Parenti quarantine the school’s troubled population. And like Hamsterdam, the program eventually gets shuttered and flushed, though this time around, Colvin doesn’t lose his job.(Hat-tip to UNC Education Professor James Trier, who clued me in on that parallel. He’s got a wonderful look at season four from the perspective of an educator.)

The Colvin storyline generates some of my favorite scenes in the series. First, check out this scene, in which Colvin takes a few of his best students to an upscale restaurant.

Once again, we see how characters who stray beyond their assigned “caste” experience discomfort. (Side note: It’s interesting to look at the characters in The Wire who are adept at moving out of their caste. Stringer was probably the best at it — he looks just as comfortable in Armani as he does in a track-suit — but even he eventually gets ripped off by the suits downtown; moreover, his efforts to abandon the drug trade lead to his death. McNulty, by contrast, is the clearest “hero” of the series, and he’s also got the advantage of white privilege, but any time he tries to leave his caste, the results are cringe-worthy.)

Back to Colvin. This storyline also features some of the most touching, heartfelt acting in the whole series. Near the end of season four, Colvin goes to Jessup to ask Namond’s father, Wee-Bey, permission to adopt the boy. This is one of the great confluences of The Wire’s overall efforts to effect societal change. A teacher asks a parent to be a better parent — and Wee-Bey’s up to the task.

It’s easy to praise Wisdom’s performance in this scene, but I want to shine a spotlight on Hassan Johnson, as well. Until this scene, Wee-Bey had mostly acted as comic relief — he loves fish! — but here we watch his heart grow three sizes in three minutes. No one’s ever going to mistake me for an expert on acting, but for me, acting’s all about what’s happening when it isn’t your line. I love how actively Johnson listens in this scene. The Wire’s all about institutions failing us, and here Colvin goes up against one of the city’s oldest institutions — the drug trade — and actually wins.

But let’s all doff our hats in honor of The Wire’s second greatest achievement, Roland Pryzbylewski. Jim True-Frost rides the bench for most of the series’ run, but after Prezbo accidentally shoots a fellow officer, he’s forced to graduate from “being a police” to being a teacher. And happily, he’s able to weather the transition between castes successfully; maybe because he’s moving laterally. Prezbo’s such a good-hearted guy, and until season four, he was a geek trapped in the macho confines of the police force. The special crimes unit gave him a place to flourish, but it wasn’t flashy. After his accidental shooting of a black detective, another officer compares Prezbo’s resume to that of the man he shot:

“How many years on for Waggoner? Six and a half. Two commendations, 16th on the current sergeant’s list. Pretty much the exact opposite of that goof in there. You know what’s in that guy’s jacket? Motherfucker flaked out, shot up his own radio car. They were gonna charge him with false report until Valchek weighed in. You know he married Valchek’s daughter, right? Fuckin’ goof had nine lives behind that shit.”

Among The Wire’s myriad themes is the conflict between alpha and beta, jock and nerd, macho and thoughtful. McNulty’s the quintessential, hard-drinking, womanizing cop, but he’s got a good heart, and watching him become a more complete person — a more thoughtful person — is one of the show’s great pleasures. On the flip side is Prezbo, who always needed to find a job where he could share his passion for knowledge. He never needed a gun, only a big cork-board.

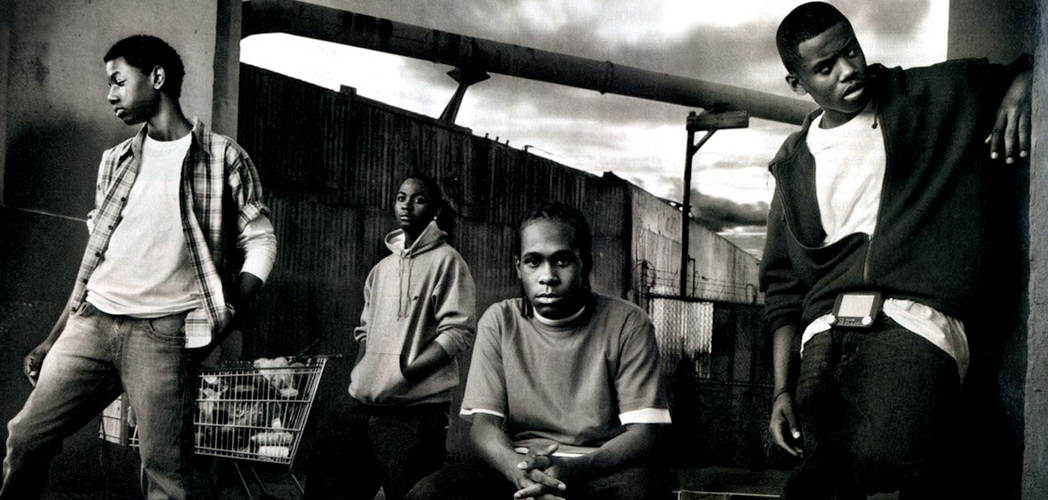

Earlier, I said that Prezbo was The Wire’s second greatest achievement. So what is its greatest? Easy — the kids. Where on earth did the showrunners find these four exemplary young actors? It would’ve been achievement enough to find one top-flight child actor; instead they found four. I’ve already mentioned Namond (Julito McCullum). He’s joined by Maestro Harrell as the precocious Randy and Jermaine Crawford as the heartbreaking Dukie.

Last is Tristan Wilds as Michael, which may be my favorite performance of the bunch, though they’re all fantastic. (Maybe I’m connecting with Wilds’ character as much as his performance.) Wilds was 17 or 18 when he shot the show, but he delivers a remarkably mature performance. He’s at a constant, slow simmer — caught between the simple world of his friends and a life on the street as a killer. On top of that, he’s been forced to process the horrors of a sexually abusive father and a junkie mother. It’d be role enough for anyone of any age, and Wilds is up to the challenge. Here’s one of his many memorable scenes, this one alongside Crawford’s Dukie:

I’m still reeling from how the show introduces four good-hearted kids, and three of them get eaten alive by the system. (If anything, that’s too generous a ratio.) Still, Namond’s end-of-narrative successes is a well-won reward. If The Wire has an overriding theme, it’s how institutions fail us, especially the underprivileged. There are no greater avatars for that theme than the four kids.

But where are they in season five?

Season five and Beyond

I know, I know — we see all of ‘em, if only briefly. We drop in on Randy in his brutal new foster home, where he’s been forced to harden his heart to combat accusations that he’s a snitch. We follow Michael and Dukie through most of season five, and even Namond makes a brief appearance in superheroic mode, kicking ass in a debate competition. Unfortunately, it’s not enough, and it’s not what season five needed, I submit.

I’m veering into “Monday morning quarterback” territory here, so I want to tread lightly. I’m arguing that season five is the weakest of The Wire’s chapter-seasons. Given the body of criticism that precedes mine, that’s not a thesis. It’s a fact. But all the same, I’m trying to grapple with why this is, and what could’ve been done to shape a more effective season. Let’s start my analysis with a look at David Simon’s own defense of season five.

From his personal blog:

“Here’s what happened in season five of The Wire when almost no one — among the working press, at least — was looking: Our newspaper missed every major story.”

Simon points out that every major storyline in season five — every real, important storyline — is back-burnered or otherwise ignored by the editors at the Sun. Simon has also noted that he himself dealt with a fabulist in his time as a Sun reporter, and that the yarn-spinner in question was a Pulitzer finalist, no less. On top of that, he notes that an important Sun editor got banished to the copy desk as a result of the fabulist, and finally, he points out that all of the cost-cutting, downsizing, and firing of experienced pros in favor of cheap, young neophytes all actually happened.

I get it. The Wire is essentially longform journalism, immersing itself in the nitty-gritty details of daily life. The show’s built on a superstructure of reportage and specific details, most of them lifted from the headlines and based on eyewitness accounts. But somehow, that technique was the wrong one for season five.

Listen, I don’t doubt that all of these things happened to David Simon while he was at the Sun. Hell, how can I doubt his word? All I can argue is that along with being journalism, The Wire is also a drama, and I respectfully submit that Simon and his team picked some of the wrong storylines for that drama.

Part of this is admirable. You can’t say they went small. They decided to make the fabulist (Thomas McCarthy’s nicely creepy Scott Templeton) a load-bearing member for the season, and that choice informed (and infected) the whole season by making it not really about anything. It silenced the echoes and flattened the layers.

Remember how in season four, every storyline was informed by the idea of schools, youth and schooling? Remember how time and again, we saw parent-child interactions among unexpected characters — Carcetti getting sent to his room until he raised enough money, for example — or how classroom-style scenes popped up in clever ways? Season four establishes this pattern expertly with Snoop’s schoolin’ of the hardware store salesman about the many uses of a nail gun. Similarly, the kids fidget in class, while McNulty and the unis fidget in briefings, while teachers fidget in seminars. Echoes and layers abound.

But season five lacks most of this connective tissue, instead opting for the on-the-nose thesis that the public will believe any shit you shovel, no matter how stinky. Here’s the opening scene for The Wire’s final season:

Are we really supposed to believe this guy’s never seen a copy machine? I guess that’s not the craziest notion the show’s ever advanced. One intriguing idea that recurs over the series’ run is how all of the denizens of Ballmer know little of the world outside of the few city blocks they own. Upon leaving Baltimore for the first time, Bodie confesses he didn’t realize there were radio stations outside the city. Later in the series, Bodie visits a park in town, noting he had no idea it existed. Even Colvin and Wee-Bey bond over a shared encyclopedic knowledge of their home neighborhood. I can buy that, but I have a hard time buying that someone wouldn’t know what a copy machine is. (Though I wouldn’t be surprised if Simon, et al, based that scene on an actual event.)

Season five’s central premise echoes into the police storyline, of course, but at great cost. Both McNulty and Freamon — two detectives par excellence — collude in the invention of a serial killer. Again, I can’t fault the writers for making a big, dramatic choice, but heretofore in the series’ run, McNulty’s rebel nature had manifested in his ability to be the best detective on the force, not the worst. Think back to the beginning of season two, when McNulty moves the watery drop-point for a dead body inside the city limits. McNulty doesn’t seem to hold his intellect in high regard, but the exacting nature with which he calculates currents, wind and drift all belie a simple mind; he’s a brilliant investigator. But no — in season five, his policing ethics desert him in favor of a mad quest to secure funding for the force.

Let me put a bow on this line of argumentation: Even if the public does believe in the Big Lie, asking McNulty (and Freamon, for crying out loud) to tell one was a misstep, I’d submit.

Moving on: It’s a shame that we rarely get to see anyone do their jobs in season five. Over at Washington City Paper, critic Mark Athitakis wrote an epic takedown of season five. (Seriously, go read the whole shebang. It’s great.) In it, Athitakis praises The Wire’s focus on work:

“The Wire is about, more than any one thing, work. Plenty of shows are set in workplaces, but The Wire is exceptionally obsessed with how business gets done, from office politics (showing up to work on time, disrespecting your boss) to macroeconomics (acquiring government funds, supply-chain management). The broken system that fucks up hard work is Simon’s chosen enemy[.]”

We lose this thread in season five, which is largely about the cops not doing their jobs and the media not being able to do theirs. I think it’s fair to say that Simon approached season five with an axe to grind. I want to quote more from his defense of the fifth season, but I don’t want to paste in too much. Please give the whole article a full read, but here’s a representative patchwork of ideas:

“It would not have been easy for a veteran police reporter to pull all the police reports in the Southwestern District and find out just how robberies fell so dramatically (…) It would be hard for a committed education reporter to acquire the curriculum of a city middle school and compare it to what children were taught before No Child Left Behind (…) But absent that kind of reporting, we will all soon enough live in cities and towns where politicians and bureaucrats gambol freely without worry, where it is never a risk to shine shit and call it gold.”

Simon isn’t wrong about any of that, but I disagree with how he presented his fundamental critique of the press — and here’s where I need to tap the brakes and make some big-time concessions. Simon was a reporter for 13 years, and he’s spent the intervening years working on some of the best longform literary journalism in all of pop-culture, Homicide and The Wire. My experience as a “reporter” amounts to a lot of freelance work, three months in a newsroom at a medium-size metro paper, the Marin Independent Journal, and three months at a tiny daily paper in Telluride, Colo., delightfully named the Telluride Daily Planet. When I got out of college, I did some entertainment writing for Space.com and wrote a few features for PerformInk, a Chicago trade paper that covers the theater and film industries. Since 2004, I’ve helped run the pop-culture website CC2KOnline.com.

I’ve spent the vast majority of my time in the journalistic world as an entertainment reporter — and if you’re asking me, entertainment reporters aren’t journalists. They’re more like PR flacks. You make connections at all the studios, and if you play nice with their PR reps, they’ll throw you a bone occasionally. It’s not journalism in the Woodward-and-Bernstein, Journalism-with-a-capital-J sense. To be sure, you have to cultivate sources on some level, but there’s no crusading, no danger, and — if you’re asking me — no real way to effect change.

And therein lies my critique of The Wire, season five: I think that mainstream journalism has become like entertainment reporting. I think the fourth estate has sold its soul to the press secretaries, and I think reporters have traded their fangs for access. Far be it from me to quote Inherit the Wind at a time like this, but it’s the duty of newspapers to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable, and we simply haven’t had a news media like that in a long, long time.

That said, Simon is right to bemoan the current state of our societal consciousness. In advancing the following views, I concede that I’m going to sound like a curmudgeon yelling at the kids to get off his lawn, but all the same I respectfully submit that the Internet’s democratization of opinion is a double-edged sword. When it works well, the mass of voices on the Internet can sound as one benevolent trumpet for the downtrodden. Look no further than the power of social media in the Middle East or in Ferguson.

On the flip side, the Internet has also helped erode our attention spans and degrade our discourse and dampen our capacity for empathy. In his nonfiction book The Shallows, author Nicholas Carr argues that the Internet may be destroying our attention spans in a very real way:

“We don’t constrain our mental powers when we store new long-term memories. We strengthen them. With each expansion of our memory comes an enlargement of our intelligence. The Web provides a convenient and compelling supplement to personal memory – but when we start using the Web as a substitute for personal memory, by bypassing the inner processes of consolidation, we risk emptying our minds of their riches.”

There are some compelling/terrifying studies out there that demonstrate that we’re already using the Internet as a secondary hard drive for our brains. Anecdotally, I can offer that I remember way less than I used to. One silly example that springs to mind: phone numbers. I used to be able to remember all of my friends’ numbers. Now I only know two — my girlfriend’s and my one of my best friend’s, and in the latter’s case, that’s only because I learned his number right before I got my own cell phone. I also remember far fewer details from movies that I used to, probably because I know I can look it up on IMDb at a moment’s notice. Furthermore, I’d argue that the anonymity afforded by the web allows for a nastiness of discourse that might not be possible if we conducted more of our affairs face-to-face or otherwise in person.

To be sure, anecdotes aren’t evidence, and the preceding paragraph is a tapestry of supposition, hunch and gut-feelings — hardly the stuff of sound argumentation. But for the sake of this article, I’d like to keep hold of this thread: that in trading its fangs for access, the media has traded depth of analysis for superficial glamor, clicks and momentary flash-in-the-pan gains.

Let me pause and add some nuance: Simon was right to pillory the media for its superficial coverage. He was right to depict a newsroom that ignored important stories in favor of glamor and blood, though to be fair, it’s nothing new for a serial killer — real or imagined — to dominate the headlines. After all, “If it bleeds, it leads.” He was also right to mourn the death of the daily newspaper. No, they’re not all dead yet, but I’d say it’s an accepted truth that the newspaper no longer holds the central place in our discourse that it once did.

But what exactly is the cause of our eroding attention span?

Is it the Internet? Is it television? Or am I — and David Simon — completely full of shit, and the reality is that we’re simply moving into a new era of technology, and that our way of thinking is changing same as it has with every new advancement in media delivery?

I have to say: I honestly don’t know. Part of me appreciates that Internet is an invaluable resource for writers and scholars everywhere, putting terabytes of data a click away. But another compelling part of me feels like we’ve finally hit a ceiling of sorts for what our primate brains can handle; that we’re wired to crave reward and novelty, and that the Internet provides a convenient place to get a fix.

And getting that fix can very quickly lead to a feedback loop.

Anyway, let’s get back to The Wire. Part of the reason I pursued that digression is because I honestly don’t know what the cause (or source) is of our eroded attention spans. I also appreciate that I may be begging the question by assuming that such an erosion has taken place.

But whatever the cause, I think that the media has lost its courage to challenge the world’s power-brokers. I wish we could have seen a storyline like that in season five — and that brings me to one of my favorite topics of essay-writing: Ways to improve. Here’s how I might picture an improved season five of The Wire:

Include a graduate from a previous season.

Way back in part one, I mentioned that seasons two and five both have a “hermetically sealed” quality. Both seasons feature new storylines that spring up fully formed from the narrative — the 13 dead women in a shipping container resulting from the dock union’s collusion with the Greek mafia in season two; the intersection of the fabulist and McNulty’s phony serial killer in season five. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course, but in both cases, the seasons lack the sense of narrative flow found in seasons three and four.

But season five’s problems are exacerbated by the lack of a true “graduate” from a previous season. No one from an earlier storyline winds up at the newspaper, which is staffed with completely new characters. Yes, there are some great performances in there, but I feel like it would have given us a better hook into the newsroom storyline if an existing character could’ve made the jump to journalism the way Prezbo made the jump to teaching.

So who would I pick to be this distinguished graduate? Easy: Namond. As the sole “survivor” of his storyline from season four, the overachieving Namond could very well have stepped into the Sun’s newsroom as an intern. Furthermore, I would have subbed in Namond for reporter Mike Fletcher. (That’s nothing against Brandon Young’s performance as Fletcher. He’s great.) The Fletcher character gave us one of season five’s best storylines: Bubbles recovery from heroin addiction and the attendant media coverage he inspired.

Wouldn’t it have been cool to see one of the kids from season four step in as a proxy for Simon himself? Namond could’ve come into the newsroom as an ambitious young college student. (At my journalism school, they shipped us off for an internship for a quarter. Maybe Namond could’ve been sent on a similar assignment.) Like many journalism school kids, Namond would’ve come into the profession with stars in his eyes and dreams of changing the world, and like everyone who leaves the profession, he’d have his hopes and dreams crushed under the heavy boot of bureaucratic bullshit.

And that’s where Simon nailed the media in season five, even if his presentation was a bit on the nose. Simon’s depiction of a newsroom ravaged by cutbacks and bad decisions rings true. The Internet has essentially destroyed the need for print editions, so only the newspapers and magazines that moved online with speed have survived the changeover.

Namond could’ve simultaneously been a great proxy for the audience and a vehicle for exposition and mentorship from Clark Johnson’s Gus Haynes. Forging a real connection between Namond and Haynes would have also harnessed an echo from season four; the classroom would’ve carried into the newsroom, and Haynes would’ve become Namond’s (and by extension, the audience’s)new teacher. On this note, it might’ve been nice to peer a bit deeper into Haynes background. Would acting as a teacher for an over-achieving intern from the inner-city resonate with him? Would it remind him of his own background, whatever that may have been?

But at the same time, I wouldn’t want to completely lose the Templeton storyline. So let’s talk about skeevy Scott Templeton and his empty notebooks.

Don’t lose Templeton, but don’t make him the focus of the newsroom.

The Templeton storyline isn’t without merit. I still don’t think that the Stephen Glasses of the world are journalism’s main problem, but they’re certainly out there, and examining one on The Wire could have provided a great way to study the overwhelming need for pinpoint accuracy in reporting.

One of my favorite storylines in season five follows Templeton as he tries to get to know the homeless community of Baltimore. His excursions into shantytowns and under-bridge camp-areas contrast with his fellow reporter, Fletcher, who connects with Bubbles and in an example of “real” journalism, not only gets to know Bubs, but he also familiarizes himself with the homeless community in a tangible, real way.

Templeton, meanwhile, goofs around the periphery of the homeless world, but for one moment, we think he might be about to change his ways. Templeton meets a young, homeless veteran and asks him about his experience in the Gulf War. He writes up the story, and it’s great — but then the same homeless veteran storms into the Sun’s offices, ranting that Scott cooked some details about the story.

It’s such a shame that this show couldn’t have gone on for another season. I’ll talk more about my ideas for future Wire seasons at the end of this piece, but I really got the sense that Simon wanted to make the homeless the centerpiece of a future season — most likely season six. We’d been hearing distant echoes of such a season since the beginning, but those echoes were growing louder and louder as we moved through season five; loud enough that a denizen of a future season (Aubrey Deeker’s homeless Iraq veteran) invades the Sun’s newsroom.

I looked far and wide for a video of Deeker’s scenes. They’re some of my favorite in the show’s run; he’s a hell of a performer. I finally tracked down his demo reel. Check out his work on The Wire at timestamps 1:23 and 2:56:

{vimeo}104584701{/vimeo}

Oh, this scene breaks my heart. Deeker’s great, isn’t he? His performance speaks to the incredible sense of honor that soldiers carry with them; that they’d never lie about a battle, because there’s nothing fun or entertaining about being in one. It’s just hell. Deeker captures that pain so very well. I mean, just look in his eyes. I also adore the writing in this scene, specifically the bit about how they weren’t drinking coffee but hot chocolate. For one, we see how easy it is to rely on a faulty memory. Templeton may not have outright lied about the coffee, but it’s telling that he couldn’t remember even that one minor detail. For another, we see how the stories of the homeless are so easily cast aside — even that of a war hero.

These are some of my favorite scenes in the series’ run, and I would have deeply enjoyed more of this kind of thing in season five, in contrast with the railroading that Haynes gets. It might have been nice to watch Templeton and Namond diverge in their reporting styles and techniques. Haynes would work with them both, but only one would really learn how to do his job. Hell, maybe even fire Templeton at season’s end. To be sure, it would mark a radical deviation from Simon’s vision to end season five with anything but unmitigated triumph for Templeton, but I still think it might have made for a better season.

Moving on, let’s talk about the cops.

What would the police storyline have looked like?

Season five found a solution for the problem of the 22 bodies. It just wasn’t the right solution, I submit. But if McNulty and Freamon don’t invent a serial killer to absorb those bodies, then what would happen?

It occurs to me that my suggestions for an improved season five are pretty clean, by Wire standards. This show is all about compromise, bullshit, and swallowing bitter pills. The Wire wouldn’t be The Wire unless some bad guys got away with murder (or with inventing a few quotes). If Templeton got fired at the end of season five, what would we have to give up in order to karmically make up for it?

Off the top of my head, those 22 bodies. As the show now stands, the actual perpetrators of those crimes, Snoop and Chris, don’t get pegged for it, though they do both die. So how could we let Snoop and Chris off the hook for those crimes, but tie it in with some of my ideas for an improved season five?

How about this: I’ve argued before that the media has traded its fangs for access to the powers that be. What if Templeton somehow uncovered that Snoop and Chris were behind the killings, but when he tries to get confirmation from the police, Rawls offers him full access to the police department in exchange for his silence? Maybe the police would feel foolish for allowing such a massacre to go on for so long. Maybe the police had found what they thought was the killer, and so had a vested interest in preserving that lie.

I feel like such a dilemma would work with Namond, too. He’s already plugged into the Ballmer drug trade in some way. Maybe his dealings with the old crew — Michael and Dukie, specifically — bring him into contact with the intel, and when he brings the news to his editors, Haynes supports him, but the Sun’s brass kill the story in favor of the offered access. (Heck, maybe Templeton could be the one who gets the offer.)

Listen, I’ve never been a TV writer, much less the showrunner of one of the greatest programs in the history of the medium, so read the following sentence in McNulty’s voice: “What the hell do I know?” But all the same, I submit my ideas for your approval.

At long last, let’s talk about my ideas for:

Possible future seasons of The Wire

The Wire was never a cop show, but rather a longform portrait of the city of Baltimore, each season a novelistic chapter that examined one of the city’s institutions: the projects, the docks, city hall, the schools, the media. But here’s the thing: At its best, those seasons were never only about those institutions, as I’ve discussed. Season one was about family. Season two was about the ideas of union and loyalty. Season three was about management styles. Season four was about schoolin’. And season five was … well, season five. I guess it was about the idea that the public will believe whatever lies you tell them, provided the lie is big enough.

So in suggesting ideas for future seasons, I’ll try to come up with settings and institutions that would lend themselves to productive themes and layered storylines. So here goes!

SEASON SIX: THE HOMELESS

In the same way that season four introduced a swath of new characters that sprang out of the new setting, so too will season six introduce four or five homeless people. Aubrey Deeker’s Hanning will anchor the lineup, which will take us under bridges, behind highway overpasses and into flophouses and soup kitchens all across the city. We’ll spend entire episodes following a homeless person as they negotiate their day — trying to score a few bucks for breakfast, visiting a free clinic for anti-anxiety meds, maintaining a particularly juicy panhandling space. We’ll see it all.

SETTINGS: The streets of Ballmer.

STORYLINE: I’d love to see an actual serial killer who preys on the homeless. After all of his shenanigans in season five, McNulty (now with the FBI) has to muster help from the local homicide department after his elaborate game of wolf-crying.

THEME/S: Remembering the forgotten; income inequality and the redistribution of wealth. I’d also like to see the show take a close look at mental health.

SEASON SEVEN: THE PRISONS

Many Wire fans have suggested this as a potential season-chapter. One intrepid fan even cut together a mock opening, complete with a new arrangement of “Way Down in the Hole.”

SETTING/S: Local jails, lockups, as well as Jessup Correctional.

STORYLINE: This season would bring season one’s major players back to the forefront. Still in Jessup on a 25-year stint, Avon Barksdale would mount a prison break. I realize that’s a pretty pulpy storyline for The Wire, but I’d love to see how Simon and his team would portray the messiness of an actual breakout. (I suspect shades of Out of Sight might ease into the narrative.) After his mid-season escape, Avon goes underground, but not before one last stop in Ballmer to take out his arch-nemesis: Marlo Stanfield. Meanwhile, some new characters enter the storyline: Correctional offiers — some new and idealistic, others old and jaded, others just plain corrupt. Freamon joins McNulty at the FBI, where they lead the charge to wiretap the offices of newly elected U.S. Senator Tommy Carcetti.

THEME/S: Rehabilitation, maintaining your identity in the face of huge odds.

SEASON EIGHT: BUSINESSES

Like the homeless, we’ve always had some sense of how businesses conduct themselves in Baltimore. Season two in particular featured an electronics store that was in bed with the Greeks, but for season eight, I’d like to see how small business owners stay afloat in the face of package stores and mega-outlets like Wal-Mart and Costco.

SETTING: Local business, Baltimore chamber of commerce.

STORYLINE: Naturally, malfeasance would play a role in the storytelling. After breaking out of prison and killing Marlo, Avon Barksdale retakes control of the Ballmer drug trade from a remote location. By the time, most of the special crimes unit has migrated to the local FBI office, setting up a manhunt for Barksdale that covers five states. Avon is eventually cornered and killed, leaving yet another power vacuum in Baltimore. McNulty, meanwhile, reconnects with his ex-wife, Elena (Callie Thorne). At season’s end, they decide to remarry.

THEME/S: Commerce, finding your way in the world, inheritance/passing on what’s yours.

SEASON NINE: CHURCHES

Remember how cool Melvin Williams was as the deacon? That’s the priest who offered advice and mentorship to Cutty while he made his transition from con to citizen. I didn’t know this, but Williams is another of The Wire’s non-actors. He used to be a major player in the Baltimore drug trade in the 70s and 80s. He even served as the model for the character Avon Barksdale. The Wire’s always been a secular show. To that end, I’d love to see a portrayal of the inner-workings of the “faith” industry told through The Wire’s journalistic lens. There aren’t many good depictions of faith or churchgoing on television. Friday Night Lights is the only non-judgmental one I can think of. The Wire would be the perfect show to rectify that deficit.

SETTING: Local churches and houses of worship across all faiths.

STORYLINE: I know it’s cheesy, but it’d be great to show McNulty working his ass off for redemption as he and Elena plan a second marriage at their local church. Meanwhile, Maurice Levy — perennial legal representation for Baltimore druglords — steps in to manage the drug trade in the absence of a new challenger for the throne. He funnels money and product through his local synagogue; at first without his rabbi’s knowledge, but later when his rabbi discovers his activities, they come into conflict.

THEME/S: Faith, belief, courage/standing for a cause, redemption.