Dinosaurs And The End Of The World: Is The Tree of Life A True Terrence Malick film?

Written by: Jacob Kunnel, Special to CC2K

The effect is that the narrative stays somehow detached from the real events of the movie (the love triangle), only to give us a much clearer picture of the times and the atmosphere of a period that is heavily influenced by industrialization and labor. Linda, who appears to be much more innocent than Holly in Badlands, still presents us with a clear picture of what she depicts, and in her, an overwhelming feeling grows. She knows that times are changing and that that this period of innocence could be (or in retrospect “could have been”) the best time of her life.

The film, through Linda’s voice-over, gives you a sad anticipation of what’s about to come, but is never really able to grab or articulate this. It’s a continuous theme in all of Malick’s next movies and it’s really effective, because through this narrative strategy, the films succeed at what most historical movies fail: Malick is able to create characters and periods where the characters are not aware of the future, where they are not influenced to a large degree by film history and certain tropes. He tries to create a world through a closed system of meaning, consisting of characters, places and details, and not through our “modern” definition of what a story should be. The characters are still figuring out what’s happening around them, and they are not able to articulate or judge it from a retrospective level. It’s happening right now.

Looking back at The Thin Red Line (1998), an adaptation of James Jones’ autobiographical 1962 novel, Malick could have shown us a “traditional” second World War film with a strong moral agenda, pretty much like “Saving Private Ryan”, which came out the same year. “Saving Private Ryan” works as film that is told in retrospect, from a perspective that is very much aware of what devastating effect WWII had on the entire world, even until now. The characters and the narrative are constructed to “tell” about WWII through a personal story. The Thin Red Line is constructed to let you “experience” WWII through the eyes of its characters, due to its impressionistic nature.

While we indeed seem to have one main character, Pvt. Witt (Jim Caviezel) with his own point-of-view, the film gives us several voice-overs from different soldiers who fight the Japanese in the conflict at Guadalcanal. Especially the death of Caviezel’s character, which happens around 15 minutes before the end of the movie, supports the idea that through the voice-overs and the different point-of-views, the personal experience of Pvt. Witt is a collective experience. And it’s an American one. This is really important in the context of Malick’s filmography, as he is one of the directors that particularly deal with the history of their country.

The depiction of a whole generation suffering from the events of WWII through a personal experience is what makes The Thin Red Line very different. It’s almost as if every voice-over belonged to the same collective mind, they don’t contradict each other much. Malick tries to articulate a shared experience that basically survives its main character’s death. Having different narrators, it’s the first time – through a slightly different narrative strategy -, that he tries to grab what that larger picture is.

The film also features some flashbacks, which gave Malick the reputation of a non-linear director. But still, they follow a very linear logic. The “flashbacks” are clearly shown as memories that appear right now, while we watch the characters thinking about the past, rather than structural flashbacks that are meant to contrast the present with the past. One could argue that contrary to what seems to be the general consensus, Malick’s strengths lie in a very linear approach. You could even say that you can’t get more linear than him. A great example is his forth film The New World.

The New World (2005) tells the well-known story of Captain John Smith (Colin Farrell) and Pocahontas (Q’orianka Kilcher), starting in 1607. Structurally, it is quite an odd movie, as it tells two love stories, the first youthful and naïve one between Pocahontas and Smith, and in the second half, a much more adult and tender one between Pocahontas and aristocratic John Rolfe (Christian Bale), narrated mainly through the voice overs of the three. The film ends with the anglicized Pocahontas, dying in England far away from her homeland.

Much as in his previous films, Malick creates a character, Pocahontas, that is overwhelmed by an incredible large new power, the invasion of the settlers, and the idea that the world might be much larger than she had ever thought. In the end it is very much her story, as it is her point-of-view that leads us through the movie, especially when John Smith disappears, spreading the message of his own death. It’s her coming of age in times of great change, we can watch how she grows up from an innocent child into someone who takes decisions that are irreversible, until she becomes a representative of her people. It’s a sad and really touching story, because this personal loss of innocence is presented as a whole people’s loss of innocence.

Unlike The Thin Red Line, the voice-over narrators, Pocahontas, John Smith and John Rolfe don’t seem to articulate the same thoughts. Instead, they love each other, but never understand each other totally, which, in the end, makes them more relatable.

While Malick sometimes gets close to the danger of presenting the natives as “noble savages”, he is more impressionistic than observational. What makes Pocahontas stand out as one of Malick’s characters is how strong and brave her behavior is, and that she has a clear motivation (something that Malick’s previous lead characters lack). Her love for John Smith and later for John Rolfe is not particularly presented as an Anglo-Saxon concept, but more as an affection for the human spirit in general. It is this strength that let’s her overcome her broken heart and find strength in a new family life with John Rolfe, although her pain can never be fully cured.

The film jumps from one moment to the next through years and decades in a very linear fashion, though it does not give the audience any structural help or orientation, nor does Malick seem to be interested in it. There is an honesty to the human experience and I believe that The New World is the most successful of the films when it comes to connecting the personal experience with the giant historical context. The effect is very unique, as it basically let’s the film appear as one giant sequence, rather than a film constructed of sequences and scenes. It’s a similar strategy to all other Malick films, as it focuses on what is happening now, and not next.

This is a very efficient and effective kind of storytelling. Malick shows us only the necessary information, without any “scenes” that only serve a structural need. There is a certain clarity to it. When I watched The Tree of Life, I felt that this very precise storytelling-technique had been replaced by something else.

Since Days of Heaven, but more prominently since The Thin Red Line, Malick has perfected a type of first-person narration that can be described as a pastoral narration. Pastoral literature is “a mode of literature in which the author employs various techniques to place the complex life into a simple one” (Wikipedia), and usually is defined by a very humble romanticized idea of nature and a simple life, mostly from an urban perspective.

While The Thin Red Line and The New World, and to some degree Days of Heaven can be described as pastoral films, they feature lead characters that struggle in really difficult political or historical situations, so it makes sense that they would crave for an alternative, a romanticized version of what life could be. The main conflict in “Tree of Life”, whose pastoral narration is somewhat structured like a Christian prayer, is much more simpler, but it is never really clear:

After the first screening I thought I had seen a film about Jack grieving for his brother’s death, who fell in the Vietnam War. But there was something odd to the idea, and the mailman didn’t look like someone from the army. But more importantly, this version felt emotionally wrong, the kind of grief was wrong. After doing some research online, where multiple articles hinted at the suicide of Malick’s brother Larry at the age of 19 (http://www.themillions.com/

I’m usually not sold onto the idea that a director’s life should have any meaning for a film review, and I do believe that Malick should have given us at least some points of orientation or clarity, but I gave it a try. Sure, the filmmaking technique is probably similar to the one in The New World or The Thin Red Line, but all of Malick’s previous events featured a strong historical context, so the audience would bring in some of their own knowledge.

Watching The Tree of Life as a film about Jack who grieves for his brother that committed suicide is definitely a much more satisfying experience, because it makes Jack’s struggle with his parents much more relevant. When adult Jack talks to his father on the phone, we get the impression that Jack has blamed his father for his brother’s suicide. Emotionally, the film is more consistent, though the structure of the film still puzzles me.

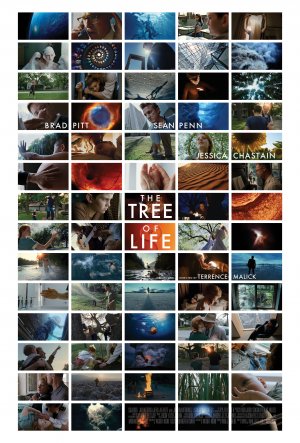

As far as I can remember, the film is split into four segments, a prologue, the beginning-of-life sequence, the main part of young Jack growing up in Waco, Texas, and an epilogue in which we see adult Jack’s idea of the eternal flame and somewhat afterlife. Personally, I find the third part about young Jack (Hunter McCracken, in the best performance I have seen this year) the most satisfying segment and I do believe that this should have been the movie and that everything else is unnecessary.

The 50’s segment starts with Jack’s birth and ends with the family leaving their home for a new place. Tonally, it’s pretty much in the same tradition as Malick’s other movies and features all of the strengths of his filmmaking style. Again we have a story about someone struggling with his place in life, while, on the greater level, we get a pretty precise picture of what the reality behind the American dream in the 50’s was. The loss of innocence is inevitable when Jack hits puberty; his sexual affection for his neighbor confuses him and the struggle with his parents hurts him.

On the surface, Jack’s father, played by Brad Pitt, is presented as the antagonist of the movie. But to be honest, I found him a much more fully fleshed-out character than Jack’s mother, played by Jessica Chastain. Sure he is flawed, arrogant and needy, but he is a human being, and he is never the tyrant another movie would make him appear to be. There is a moment where young Jack tells his father that he believes his father wants him dead. While we know everything about Jack’s inner struggle, his father is just confused and a bit frightened by the words of his son. While this segment is clearly told from Jack’s point-of-view, it is really interesting how we, as adults, can shift to Mr. O’Brien, because Brad Pitt’s portrayal is so nuanced that we can also see a young father realizing that his idea of how to raise kids is failing.

This ability to have one distinct point-of-view (young Jack), while giving the audience enough room to shift their attention to a character like Mr. O’Brien, shows that Malick has grown as a director. His previous films were much more singular. With The New World, he for the first time created characters that are totally different, but could exist in the same world, giving them their own voice-over narration. Although we have a short voice-over by Mr. O’Brien, his character is not defined by the voice-over narration, which makes it much more poignant.

Jack’s mother, on the other hand, is not established as a real character. Although there are several occasions where she struggles with her husband and even with Jack, her motivation and her needs are not quite clear. While she indeed has her own way of raising their kids, she is never really relatable as a fully fleshed-out human being. She is presented as a saint, as an angelic figure, and while I do not doubt that a person like this could have existed at that time, it is not really engaging in a sense that I care about her. And she is indeed an antagonistic force, much more than the father, especially when Jack’s crush on his neighbor is obviously related to his mother.

While I do believe that Malick could have put more effort in the presentation of her character, something else occurred to me: The theatrical cut of The Tree of Life tells us that this is clearly adult Jack’s memory, while the 1950’s Texas segment follows the narrative style that Malick has perfected throughout his previous films, and that I have described in this essay, – presenting an experience that takes place in the very present.

As the film is told from the retrospect, it is not quite clear if what we see are young Jack’s experiences (a single character, who is experiencing everything now, much as Pvt. Witt in The Thin Red Line or Pocahontas in The New World) or if they are adult Jack’s memories, which would explain the portrayal of the mother.

If I had to answer this question I’d say it’s young Jack’s experience and adult Jack’s memory at the same time, it’s both. And that’s probably the best thing Malick has ever done.

With this segment, he has created an ambivalent portrayal of memory itself. The flaws of the story (portrayal of the mother, disorientation) become an integral part of the storytelling-technique. The nostalgia of the memory itself becomes an antagonistic force, because the “facts” get lost in the memory. It’s a very honest and impressionistic portrayal of a character that is experiencing his own history while looking back at it as a memory.

I don’t believe that all of this was fully intended, much as the final cut of Days of Heaven was not intended at all. Maybe the merging of these two point-of-views are a result of Malick’s intention to make a film about grief that juxtapositions a single life with the beginning and the end of the world.

Intentionally or not, I believe that the third segment of The Tree of Life should have been the entire film, and that everything before and after is not only unnecessary, it even hurts the movie. It practically kills all the ambivalence and truthfulness by transforming the pastoral story into a spiritual, religious prayer.

It also becomes quite a reactionary, conservative film. The whole juxtaposition of “nature” and “grace” is definitely an interesting concept, but by dictating it onto the material, the film tries to constantly defend itself that everything is of much higher meaning than what you see. It’s like talking to a patient in a mental institution, who starts to talk about his own life and his problems, and then pretends that everything is connected to the beginning of the world. Malick might have been influenced by Kubrick’s “2001 – A Space Odyssey”, but Kubrick was a different filmmaker, much more controlled than Malick, but his characters were also less emotionally engaging.

The main problem I have with the theatrical cut is that I’m not sure who exactly is telling this story, something that has been always very clear in his other films. If this is Jack’s story, why does it start with the mother receiving the message of her son’s death? Why can’t we see Jack receiving the message? I believe you could cut all the scenes out in which you see adult Jack and his mother grieving. Why?

Because it’s all present in the 1950’s segment. In every single frame of this segment you are aware that these kids are going to die one day. The way he portraits the three brothers, there’s an ongoing sadness under the surface. The fragility of life is so much stronger when presented by the child actors and the way Malick and Emmanuell Lubezki, the director of photography, frame every single image tells you the whole story on a thematical level. The themes of life, death and memory run through every single picture. You don’t need to see Sean Penn, you don’t need to see Jessica Chastain grieve.

Malick masterfully takes us back into the 50’s, but he is less successful in presenting us a clear vision of the world adult Jack lives in. Blurry streetlights and shots of grayish skyscraper offices give us no real impression what life thirty years later could be like. Of course, adult Jack is supposed to be lost, but the director seems to be lost, too, when he needs to portray this period. It’s just confusing, and it clearly doesn’t help a film that is so great at nuances and details of the world the characters live in.

So what about the beginning-of-the-world segment? While I really enjoyed it at the first screening – the visuals are unbelievably beautiful, the musical selection is impressive – I couldn’t get rid of the feeling that I would enjoy theses images more if they were part of a “National Geographic” documentary (it is rumored that these segments were originally produced for Malick’s origins of life documentary). Also, I felt that the dinosaur scene was kind of ridiculous, and the CG-animation was not particularly well done.

At the second screening of the film, there was one image in the 1950’s segment that stuck to my mind. It’s one of the kids, probably Jack, reading a Sci-Fi novel at night with a torch. In the book there is a large image of astronauts on a planet in space. It then occurred to me that this film tells us everything that the beginning-of-the-world-segment tries to tell. And more. Here we have a little boy, a young adult, who is trying to grab the scale of the entire world that he lives in. Through this image, you see the beginning of the world, and you feel it. You don’t need to show it.

The same can be said for the ending of the film, what has been referred to as “afterlife” or “the eternal flame”. Questions of life, death and afterlife are already present in the 1950’s segment, when one of young Jack’s friends dies in the swimming pool, or when he imagines his mother in a glass coffin. These images are so much more powerful, because they are told through a distinct personal perspective.

Connecting just glimpses of the beginning-of-the-world-segment and the-eternal-flame-segment with one of those more poignant scenes would serve the film much better than the overly religious and reactionary way the theatrical cut is structured.

The ending of the film is unfocussed and feels way to long. The concept of “nature” vs. “grace” is intriguing, because it is a struggle and not because one side wins in the end, which is what I get out of the ending. Here, the mother’s grace is presented as the right solution to everything. And if “grace” wins, does that mean that the mother has been always right, and the father always wrong?

If so, I find the way both of the parents are “judged” troubling, because the father seemed so much more to be real person. The problem is that Malick’s strength is to present stories that take place in the present, where you can only anticipate the future. Here he gives us “the future” and it is unsatisfying, because the greatest stories are those that are not finished, because life can never be finished.

After watching The Tree of Life a second time and revisiting Malick’s short filmography, I do believe that the theatrical cut of his latest movie feels like an unfinished version of a better film that is more in line with the strengths of Malick’s previous films. The Tree of Life does not need to be a preachy spiritual experience, it could be something more effective, a human experience. It could be a very personal story about the loss of innocence in times of giant change. Sometimes, you need to kill your darlings, and the ones in this film are of giant proportions, but deleting those scenes would make this film a much more human and clear experience: The simple story of young Jack’s loss of innocence in 1950s Texas, told from what could be a memory in a moment of grief.

All synopses of the 5 movies taken from IMDB.com