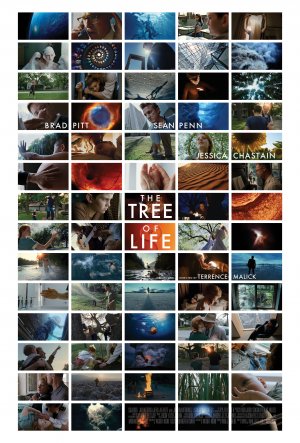

Dinosaurs And The End Of The World: Is The Tree of Life A True Terrence Malick film?

Written by: Jacob Kunnel, Special to CC2K

Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life has been the subject of many reviews and discussions since the film premiered at this year’s 2011 Cannes Film Festival and won the Palm d’Or. While it stood out from the rest of the competition due to its unique style and narrative strategy, many of the early reviewers didn’t seem to be sure what they exactly saw, a pretentious, over-the-top art-house-movie or a spiritual experience that dealt with serious questions of life, death and memory. There was also an underlying feeling that Malick, whose filmography consists of only five released movies so far, has been honored for his lifetime achievement, rather than for his achievement on The Tree of Life.

Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life has been the subject of many reviews and discussions since the film premiered at this year’s 2011 Cannes Film Festival and won the Palm d’Or. While it stood out from the rest of the competition due to its unique style and narrative strategy, many of the early reviewers didn’t seem to be sure what they exactly saw, a pretentious, over-the-top art-house-movie or a spiritual experience that dealt with serious questions of life, death and memory. There was also an underlying feeling that Malick, whose filmography consists of only five released movies so far, has been honored for his lifetime achievement, rather than for his achievement on The Tree of Life.

Being one of the last great auteurs in cinema whose filmography spans over a few decades, Malick’s films have become something of its own genre, much like the films of Stanley Kubrick or newer talents like Darren Aronofsky, Christopher Nolan or Gapar Noe. But what exactly is a “film by Terrence Malick”? There seems to be a general consensus that his films are dream-like, non-linear experiences that work like visual poems, and not like traditional films that follow a certain linear logic.

While most of the attributes seem to be right, it is hard to review a film under these predetermined definitions. A Malick film is still “just a movie”, and will still have its flaws and unique moments.

When I watched The Tree of Life for the first time, I was very influenced by the huge online response, the lush trailer and the anticipation for a film that had been delayed for over a year. Terrence Malick is probably my favorite working director, and I have a very close relationship to his movies, although they sometimes leave you with an overwhelmed and heavy feeling, which doesn’t really make you want to watch them again immediately.

That’s exactly the reaction I got out of that first screening. I was overwhelmed, I loved the images and I really disliked the ending. Just a few minutes after the screening I got the feeling that something was really wrong with the way Malick had presented his story. It felt less “honest” than his last movies. Something was way off, and it had to do with the beginning and with the ending, and the general pace of the film. I had to watch it again to find out what really bothered me.

The Tree of Life tells the story of Jack O’Brien (Sean Penn), who, now an adult, grieves for the death of his younger brother and remembers his youth and coming of age in 1950’s Texas. These memories, which deal with the loss of innocence and the complicated relationship to his authoritarian and competitive father and his tender, but overbearing mother, make up the largest part of the movie.

While some of the synopses and reviews will focus entirely on the 1950’s Texas setting or on the giant sequences of the beginning of the world (including the now famous dinosaur-scene), I feel that summarizing it from the Sean Penn character’s point-of-view is the most honest way to describe the theatrical cut.

What I love about each of the five Malick movies (including The Tree of Life) is how they tell very personal stories about the loss of innocence in times of giant change. It is this complex relationship between the individual and the overbearing power of history that, to me, is the heart of his movies. I’m not even sure if this was always intended, but there’s something really intriguing in the relationship between the very personal, voice-over-driven first-person point of view of his protagonists and the unique visual imagery that creates a god-like perspective, a third-person omniscient point of view.

Looking back at his debut feature Badlands (1973), which can be considered his most conventional film, this dichotomy is already very obvious through the character of the teenager Holly (Sissy Spacek), who follows her 25-year-old boyfriend Kit (Martin Sheen), a garbage collector, on a killing spree through the Dakota Badlands (The film was inspired by the real Starkweather-Fugate killing spree in 1958).

At first, Holly seems to be a very simple-minded character. Her naïve voice-overs and her girlish behavior seem to show a person that is not very capable of understanding the danger and violence around her, especially after her father is murdered by Kip at the beginning of the movie. Her behavior seems rather ignorant, especially when she doesn’t seem to have any real feelings for Kip himself, even at the end, where her voice-over, without any emotion, explains that Kip will get a death-sentence and she will get away with a suspended sentence and marry the son of her lawyer.

What makes the character of Holly and Sissy Spacek’s performance so captivating is the feeling that she could be an unreliable narrator. That she pretends to be someone who is detached from the violence that is happening around her and that her voice-over is aware of the platform that is given to her, almost as if she was on TV. This shift in the reliability of the character suggests another story that is told.

The film’s main focus is not the violence itself. Instead, the characters are so detached from the violence, because they seem to be part of a greater picture, a generation that is influenced by a general traumatic experience, might it be the aftermath of the second World War, the struggle between the young and adult and the change of the white middleclass in the 50’s or, in retrospect, everything that led to the trauma of the Vietnam War (The film was released in 1973). Although the characters give us the point-of-view of the movie, they are only part of a larger picture.

Told in not-so-far retrospect, Days of Heaven (1978) presents us with a similarly puzzling character: In the early 20th century, a young girl named Linda (Linda Manz) leaves Chicago with her older brother Bill (Richard Gere) and Abby (Brooke Adams), the woman he loves, to escape poverty. When they find employment on a farm in Texas, Bill convinces Abby, who acts as their sister, to marry the dying farmer (Sam Shepard) to claim his fortune.

The really fascinating fact is that due to the improvisational nature of the shoot, Linda’s voice-over was added in the editing room to “save” the movie (watch producer Jacob Brackman’s explanation here:

What originally was supposed to be a story about a love triangle became a story about a young girl and the loss of innocence, making Linda’s perspective the main point-of-view.