Deconstructing the Manic Pixie Dream Girl

Written by: Beth Woodward, CC2K Books Editor

I have a problem with the Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope—but it’s probably not the one that you think.

I have a problem with the Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope—but it’s probably not the one that you think.

Maybe it’s because I’ve been hearing a lot about Zooey Deschanel’s interview in Glamour in which she declared herself a feminist. The blogosphere has given her a lot of flack, both before and since this interview; after all, how can a woman to epitomizes the Manic Pixie Dream Girl be a feminist?

Let’s start by defining our terms here. The term originated in an AV Club review of the movie Elizabethtown (which I’ve never seen). The author, Nathan Rabin, says, “The Manic Pixie Dream Girl exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures.” In popular usage, the Manic Pixie Dream Girl has been used to describe a female romantic interest who brings the male lead out of his shell.

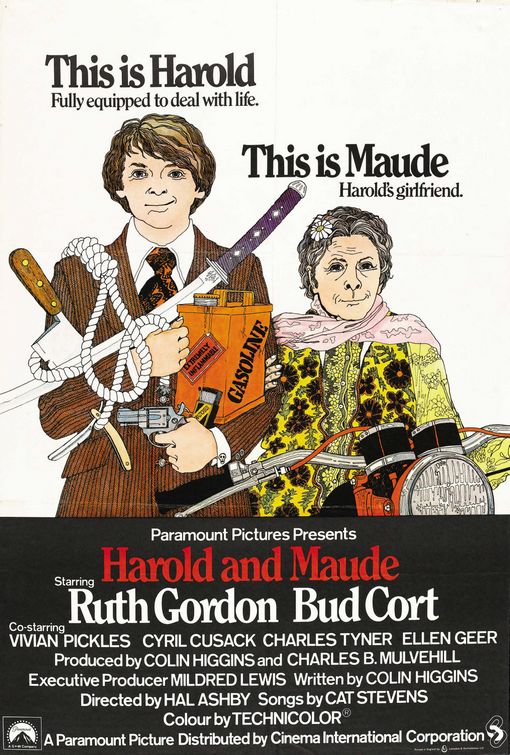

My interest might have something to do with the fact that, upon hearing more and more about the Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope, I learned that Maude from my favorite movie, Harold and Maude, is sometimes cited as an example of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl Trope. (Never mind the fact that Ruth Gordon’s Maude is 80 in the film—not a “girl” by any stretch of the imagination.) Annie Hall in Annie Hall, and Penny Lane in Almost Famous—two more films I hold near and dear to my heart, have also been called out as examples of the trope. Hell, if you consider this page as accurate, almost any quirky female character could be considered a Manic Pixie Dream Girl.

But wait a minute—I’m quirky! I’m even sort of girly, which is often discussed in relation to the Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope. I wear retro-style dresses and headbands. I have a tendency to spontaneously burst into song and/or dance at random moments. (I really do. Ask my coworkers.) I love cute kitty pictures, and I’ve got pictures of my own adorable cat up all over Facebook and my desk at work. I like to cook. I read romance novels and watch chick flicks, and I’m not ashamed of it. My aesthetic sense is pretty much, “Put as many bright colors in once place as you can.” If I didn’t work in such a conservative environment, I’d put blue streaks in my hair to match my eyes. Does this make me a Manic Pixie Dream Girl?

The obvious answer is no. But in reality, it depends on who’s looking at me.

The reason that the Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope often gets attacked is because these female characters are often perceived as static, without an inner life of their own. They exist solely to provide awakening and catharsis to the male lead. But the main commonality of these characters is not that they’re quirky, static, or even that their function in the movie is solely in relation to the male lead. It’s that all of these female characters are seen exclusively through the lens of the male lead.

Let’s take some examples:

Maude, Harold and Maude. I’m a little biased here, because this is, as I said, my favorite movie. Harold is a rich, disaffected 20-something who stages fake suicide attempts and attends funerals of people he doesn’t know. Maude is a week away from her 80th birthday, and she’s vivacious and full of life and spirit. She awakens a zest for life in him with car thefts and Cat Stevens songs.

Is Maude a Manic Pixie Dream Girl? Well, she’s certainly quirky. She is also, I have to admit, a static character. Her role in the movie is to help Harold find the joy in life. We only get tiny glimpses into her life before Harold: the concentration camp tattoo on her arm, a short talk of revolts and a former sweetheart named Frederick, her disdain of cages. But the point of view of the movie is Harold’s. Thus, we only get to see Maude through Harold’s eyes—and Harold is so damn self-involved during most of the movie that it would never occur to him to ask about Maude’s past.

Penny Lane, Almost Famous. Kate Hudson’s Penny Lane is a “Band Aid” (i.e. groupie) traveling with a band called Stillwater and sleeping with the married guitarist. When 15-year-old aspiring journalist William meets her, he is immediately smitten. (As was I: I still maintain that this is Kate Hudson’s best performance.) Penny is everything a good Manic Pixie Dream Girl should be: fun, lively, passionate, spirited, beautiful. Take this scene, for instance:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v= ccvdDTqo95s

Once again, we have an example of a female character being seen primarily through the eyes of a male character, in this case, William. Part of William’s maturation process is realizing how screwed up the rock-and-roll lifestyle—and Penny’s role in it—really is. I would argue that Penny isn’t really a static character, though. In the end, she ends her relationship with the married guitarist and travels to Morocco, as she had always dreamed.

Summer, (500) Days of Summer. This is the picture that people often cite as Zooey Deschanel’s prototypical performance as the Manic Pixie Dream Girl. After all, Summer is quirky, girly, and vivacious—but most of all enigmatic. Her hot-and-cold behavior toward Tom seems inexplicable throughout most of the film. (The non-linear presentation of their relationship doesn’t help any.) Tom’s a really nice guy, after all. He’s sweet and devoted to her. From that perspective, Summer really does seem like a bitch. In fact, it was one of the main complaints about her character after the movie was released.

But once again, we only see Summer and the relationship through Tom’s eyes. In fiction, we would call Tom an unreliable narrator. At one point, we get to see just how much Tom’s expectations diverge from reality.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v= fQb_zGR-ap8

Tom is so oblivious that he goes to a party hosted by Summer, and he doesn’t even notice she’s wearing an engagement ring!

There’s also a great scene near the end of the movie where Tom looks back on the relationship and sees, in retrospect, all the little signs Summer was giving off that showed she wasn’t completely happy. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find it on YouTube. But again, it shows just how much Tom was missing.

Think of how this movie would play out if the story were told from Summer’s perspective instead of Tom’s. She’d get involved with Tom, and she’d like him, but she wouldn’t be completely happy. Tom is kind of emotionally needy. Plus, he’s wasting away in a job he doesn’t really want instead of pursuing his dream of becoming an architect. She breaks up with him, and she tries to be nice about it, but then he gets really weird and stalkery. She knows she totally did the right thing. Then she meets someone else who isn’t so clingy, is following his dreams, and doesn’t stalk her. She falls in love with him and gets married. The end.

By itself, seeing characters through the lens of the male leads isn’t inherently a bad thing. I’ll admit that the Manic Pixie Dream Girl characters are often lacking dimensionality, whether that’s intentional or unintentional on the filmmakers’ parts. But that’s a point-of-view issue, and it happens in real life as well as movies. I may not really be a Manic Pixie Dream Girl, but I can tell you that I’ve been seen pretty much that way in some of the relationships I’ve been in. Guys have, on occasion, taken my superficial self and then projected onto me what they wanted me to be. I suspect it happens quite a bit in budding relationships. (In all fairness, I’ve probably done the same thing to some of the guys I’ve dated.) The Manic Pixie Dream Girl is merely a cinematic reflection of this phenomenon.

So why, then, is the Manic Pixie Dream Girl a big deal? After all, point of view is a device used in a lot of movies, and if the underdeveloped nature of some of these characters is a reflection of the point of view of the film, why should it be considered a problem?

By itself, it’s not. But I think the real reason people gripe about the Manic Pixie Dream Girl is one that doesn’t get articulated very much. The reason we notice the Manic Pixie Dream Girl is because a disproportionate number of movies are told from the male perspective. Most are written and directed by males. That’s not to say that men can’t write complex, multi-dimensional female characters—many can. But the fact remains that most men write male characters. As such, males get to be the lead characters in most films, relegating females to supporting parts. By its very nature, the Manic Pixie Dream Girl will always be a supporting character. It stands out because there are so few other types of female parts to compare it to.

So how do we fix it? We need more female directors and writers in filmmaking. With more female writers and directors, we will see more complex, varied female parts.

Tropes are part of the filmmaking world, and by themselves they’re not necessarily a bad thing. But until we have more diversity of female parts, female-centric tropes like the Manic Pixie Dream Girl are going to seem problematic—if only because we don’t have enough nuanced female characters to counteract them.