‘American Factory’ Highlights the Inhumanity of Capitalism in the Story of a Dayton Factory (Tribeca 2019)

Written by: Lauren Humphries-Brooks, CC2K Staff Writer

Every year, the Tribeca Film Festival features an extensive slate of documentaries covering everything from environmentalism and personal journeys to abuse cases and politically conscious dissertations. This year, one of the best to come out of the festival is American Factory, a documentary that deals with the complexities of global capitalism, the downturn of American business, and the concerns of workers worldwide.

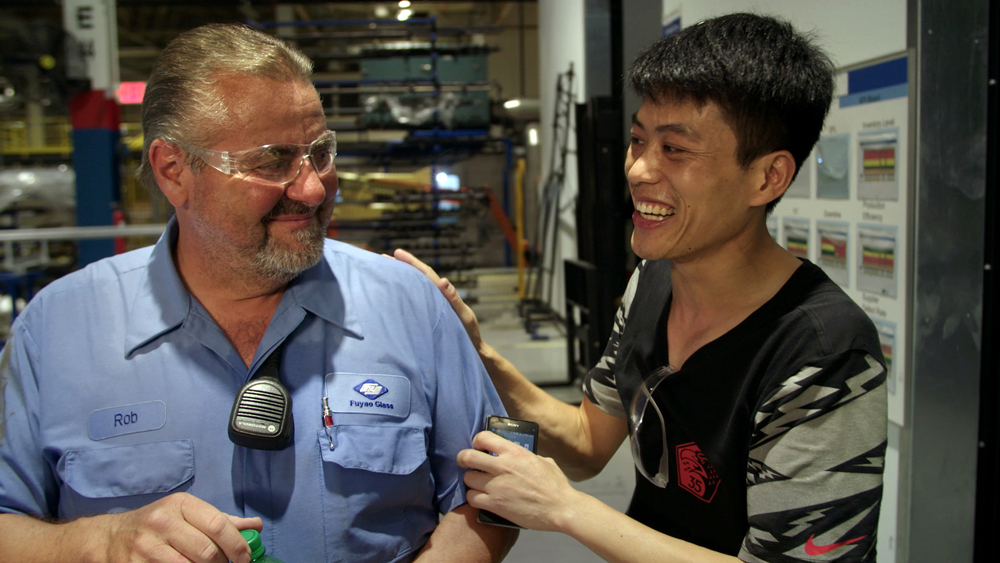

American Factory tells the story of a former GM plant in Dayton, Ohio, bought by a Chinese billionaire who runs Fuyao Glass, which supplies nearly 80 percent of the glass used in automobiles worldwide. At first, the arrival of Fuyao seems a godsend to the laid-off workers: the company promises to bring in new jobs, rehire many of those who lost their livelihoods with the decline of American automobile manufacturing in the aftermath of the Great Recession, and provide an upswing in the standard of living for the city’s working and middle classes. But the undercurrents are already there: Fuyao brings in a set of Chinese workers and supervisors, there initially to show the American workers how to run the factory and then, supposedly, turn over the work. But as the film proceeds, more than mere culture clash and language barriers crop up between the two groups, and American Factory turns into a riveting, at times depressing, and occasionally hopeful argument against capitalism, showcasing the intense toll it takes on the bodies and souls, Chinese and American alike.

The Chinese workers are themselves discouraged from participating too much in American culture or becoming friends with their colleagues—their essential “difference” is emphasized by the language barrier, but also by their supervisors’ continued reiteration that they are better and stronger than the Americans, whose adherence to things like safety concerns and possible unionization is treated as lazy, childish, and dangerous. The degree of ethnocentrism coming from the Chinese supervisors is shocking at times, as Americans are compared to donkeys and children who must be taken in hand. Yet the documentary doesn’t attempt to frame these concepts with editorializing from the filmmakers, instead allowing the people to speak for themselves. As the film goes on, it’s clear that the Chinese owners and managers are interested not just in bringing Chinese companies to America, but also propagating “work until you die” values. In this, the capitalistic tendencies and contempt for the workers is shared by the American supervisors—in one sequence, an American supervisor on a tour of a Chinese factory remarks how much more “loyal” the Chinese workers are, working long hours with no vacation time for little pay. He bemoans American laziness, the need for a weekend, vacations, and benefits, and even wishes that he could “put duct tape over their mouths” to stop them from socializing at work. This scene catalyzes the film’s argument, informed as it is by an interview with two Chinese workers who say that they’re exhausted and often don’t see their children for months or a year at a time, but have to continue to work because it’s a better job than having nothing at all.

Loyalty to the company is paramount in Fuyao’s methodology, but what is most terrifying is how the American managers are clearly excited by the degree of regimentation and false joy the workers express about their company. The Americans want to force their own workers to become like that. This feeds into the film’s other concern, as workers at the Fuyao factory in Dayton find that they are being underpaid for long hours working in dangerous conditions. They begin to make noises about unionization and talk to the local UAW, prompting an immediate effort from the company to quash any attempt to unionize. The film briefly highlights the way that current American laws have limited the powers of unions, and the arguments about unionization highlight both the perceptions about unions (that they take your money and give you nothing) and the cultural impact of poverty and lack of jobs for workers skilled in a dying industry. Aren’t we all just a big, happy family? Why would you want to ruin that?

The “loyalty to the brand” and “we’re all family” concept is hardly foreign to American business. Companies from Google and Apple, to Macy’s and even many colleges and universities utilize the idea that employers are your friends and family members, that bringing in a union would “disrupt” that joyful relationship. The resonance in American Factory should remind all of us of the rhetoric that companies across industries use to keep workers from unionizing or even from asking questions about their own safety, emotional welfare, and salaries or wages. The dystopian images from the “celebration” of Fuyao in China, as Chinese workers dance and sing songs to the glory of the company and the chairman, is not a far step from where many American industries are right now.

While the film is evidently about a slice of American working class life and business, it has broader implications. The dehumanization of workers by the managerial structure, the contempt for them, and their lack of representation at a higher level is common throughout the business world. Loyalty to a brand or a company is inculcated everywhere and saying bad things, or wrong things, about the company, while not illegal, can result in tacit punishments and eventually dismissal. Whether intentional or not, American Factory represents a powerful argument against the capitalist structure by presenting the essential, common humanity of the workers, Chinese and American, against those who would prefer that they simply work until they drop dead. It is an argument for humanity against callous economics, and humanity must endure.

American Factory is now at the Tribeca Film Festival.